The Bachelors: Pawns in Duchamp’s Great Game

Many metaphors borrowed from chess have

taken their place in the vocabulary of everyday

life…. Perhaps the commonest in modern usage is to represent diplomatists,

politicians or

anybody who is pursuing a large plan without revealing his ultimate intentions,

as engaged in a

game in which the Pawns are the innocent tools with which the plan is

carried through

(Murray, History 537).

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride

Stripped Bare by

Her Bachelors,

Even, 1915-23

© 2000 Succession

Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Marcel Duchamp’s obsession with chess, for which he professed to “quit” making art in the early 1920s, has been meticulously documented by critics and historians. Virtually all of the principal studies of Duchamp’s career make reference to his lifelong association with the game, from his early drawings and paintings to his pursuit of the French Chess Championship. However, despite the abundance of literature concerning Duchamp’s many chess-related activities, scholars have, for the most part, neglected to regard the history of the game as a potential resource for imagery in Duchamp’s work. One segment of the history of chess, the evolution and symbolism of the individual chess pieces, may have been particularly appealing to Duchamp. In fact, one of the chief elements of Duchamp’s monumental The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even or The Large Glass of 1915-23 (Fig. 1), namely the Nine Malic Molds, appears to have been derived from chess-piece history.

According to Harold James Ruthven Murray, England’s foremost chess historian, there were a number of popular sermons written in the thirteenth century collectively known as the chess moralities (History 537-49). These sermons were intended “to give instruction to all ranks of men by means of instances drawn from Biblical, ancient and modern history” using “the chessmen as typical of the various classes of men” (Murray, Short History 34). Due to their strong similarity, I believe that Duchamp modeled his malic molds after these allegorical chessmen – specifically the pawns – in the moralities, which he may have encountered through a number of sources. To support this proposition, I will consider the extensive influence of chess on the life and art of Duchamp, followed by a thorough study of the evolution of the molds and their remarkable concordance with the medieval allegorical pawns.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 2

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Jacques Villon,

La Partie d’échecs, 1904

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

The Chess Game, 1910

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

The Chess Players, 1911

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

click images to enlarge

- Figure 5

- Figure 6

- Figure 7

- Marcel Duchamp,

Portrait of Chess Players, 1911

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

King and Queen Surrounded

by Swift Nudes, 1912

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp, Trébuchet, 1917

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

It is perhaps prophetic that, at the age of thirteen, Duchamp was taught both painting and chess in the same year (Schwarz 1:64). A 1904 etching by Jacques Villon of a seventeen-year-old Duchamp embroiled in a match with his sister Suzanne (Fig. 2) testifies to his continued interest in the game. Three of Duchamp’s major works during the years 1910-11, The Chess Game, The Chess Players, and Portrait of Chess Players (Figs. 3-5), not only indicate the pervasiveness of the game in his life and art, but also foreshadow the complex strategies he would use both in his art and in his often antagonistic relationship with art world officials. While Robert Lebel stated in his influential biography of Duchamp that “chess seems to have had less place in his life from 1912 to 1922” (48), a brief survey of those years shows that Lebel’s assessment is clearly not the case. In 1912, shortly before he ceased working in traditional media, Duchamp executed a number of studies and an oil based on the theme of, according to Arturo Schwarz, “a mythical king and queen of chess” (1:64). This king and queen, a motif that Duchamp explicitly stated was derived from chess (D’Harnoncourt and McShine 260), formed the core of The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Fig. 6), in which Duchamp married the Nude Descending the Staircase of the same year with the static royalty of the chess figures. In 1917, Duchamp “accidentally” discovered one of his readymades when he nailed a coat rack to the floor of his studio (Fig. 7). He named this discovery Trébuchet or “trap,” which is chess jargon “for a pawn placed so as to ‘trip’ an opponent’s piece” (D’Harnoncourt and McShine 283).

click to enlarge

Figure 8

Marcel Duchamp,

Poster for the French Chess Championship, 1925

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

By 1918, Duchamp was living in Buenos Aires and, in addition to being in the midst of the preparations for the Glass, devoting more and more time to chess. “I have thrown myself into the game of chess,” Duchamp said in 1919 (qtd. in Naumann 12), and, upon moving to New York in 1920, became a member of the Marshall Chess Club. Between 1923 and 1925, he played in several competitive chess tournaments against some of the finest players in the world, and surprised many by winning the Chess Championship of Haute Normandie in 1924 (Keene 125). He was pronounced a Chess Master by the French Chess Federation in 1925, the same year in which he designed the poster for the French Chess Championship in Nice (Fig. 8). While this short survey of chess in Duchamp’s life and art covers only twenty-five years of a long and distinguished career and leaves out many interesting and interrelated activities in both fields, it is clear that his contributions to both pursuits did not go unrecognized. His achievements are commemorated by his inclusion in The Oxford Companion to Chess, in which he is named “the most highly esteemed artist to play chess at master level” (Hooper and Whyld 116).

With this in mind, it would be difficult to argue that chess did not in some way play a role in the formation of the largest and most complex project of Duchamp’s early career, The Large Glass. Affinities between the Glass and chess have been previously noted, such as Yves Arman’s observation that Duchamp “arranged all the elements of the bride on one side, and all the elements of the bachelors on the other, and one can easily consider that their relative position or intended interaction have a lot to do with a game of chess” (19). While it would be futile to attempt to summarize the various aspects of the Glass, which consists of equal parts engineering, chemistry, physics, chance, humor and fantasy, it is significant to note that the Glass is both a sculpture and a mechanism, albeit a mechanism of conceptual rather than mechanical intent. The individual parts do not move; the mechanistic aspect of the Glass is entirely up to the imagination of the viewer. This aspect of the Glass corresponds strongly with comments Duchamp made about chess. In more than one conversation he made reference to the plasticity of the chess game, and described it to Laurence Gold as a “mechanistic sculpture” (qtd. in Schwarz 1:72). Though the pieces in a chess game do move, it is important to remember that the pieces are merely physical markers for a contest that is principally mental. Indeed, many of the great masters of chess played matches without ever looking at the board during the game, a type of play called blindfold chess (Hooper and Whyld 45). Thus, as in chess, the components of the mechanism of the Glass are not automatic, but require the visualization of the movement of the mechanism in order to play out the scenario.

Of the various sections of the Glass, the one that seems to have an especially close relation to chess is the Nine Malic Molds, which Calvin Tomkins noted “at first glance resemble chessmen” (89). The nine molds comprise the Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, which, according to Duchamp, “represents nine moulds or nine external containers of the mouldings of nine different uniforms or liveries” (D’Harnoncourt and McShine 277). Because my analysis is primarily iconographic, I will not discuss the complicated function of the molds and their relation to the Glass as a whole. However, I will attempt to trace the development of the molds within Duchamp’s career.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 9

- Figure 10

- Figure 11

- Marcel Duchamp,

The Reservist, 1904-05

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

Policeman, 1904-05

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp,

ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - The Undertaker, 1904-05

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Duchamp began to show an interest in uniforms as early as 1904-05, when he executed numerous sketches of a variety of professions. Several of the occupations he depicted in these studies, including the reservist (presumably the antecedent of the gendarme), the policeman and the undertaker (Figs. 9-11), would reappear as molds in the Glass. It is clear from the majority of these sketches that Duchamp’s primary goal was to record the principal details of the various costumes rather than the individuals themselves, since most of the figures have either roughly delineated or no facial features. Moreover, Duchamp sketched several of these individuals, such as the policeman, from behind, concealing their faces completely. By the time of their inclusion in the Glass, these uniforms would be divested of the bodies completely, since the individuals wearing the uniforms did not contribute to the understanding of the clothing as representative of its respective profession. It is significant at this point to note that all of these early sketches are of men, and that each of the vocations depicted is, according to Tomkins, “an occupation for which there is no female equivalent” (89).

click images to enlarge

- Figure 12

- Figure 13

- Figure 14

- Marcel Duchamp,

Dimanche, 1909

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS,

N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

Mid-Lent, 1909

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS,

N.Y./ADAGP, Paris - Marcel Duchamp,

Portrait of Gustave Candel’s Mother, 1911-12

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

John Golding has linked the Molds to a cartoon by Duchamp titled Dimanche of 1909 (Fig. 12), in which a pregnant woman is walking down the street accompanied by a man, presumably her husband, who is pushing a carriage containing a baby (66). According to Golding, the juxtaposition of the pregnant woman and the occupied carriage indicates that Duchamp was “thus unequivocally making a parallel between her body and the machine/container” (66). Like the pregnant woman and the carriage, the molds are essentially containers, and thus perpetuated Duchamp’s fascination with “the idea of the body as an empty vessel capable of receiving other substances into it” (Golding 66). Another cartoon from 1909, titled Mid-Lent (Fig. 13), shows two seamstresses working on a dress that is mounted on a dress form. This headless, armless, and, though the lower portion is covered by the dress, presumably legless dress form bears a strong resemblance to a study for one of the molds executed four years later. Duchamp continued to explore the theme of a torso or bust resting on a base or stand in his Portrait of Gustave Candel’s Mother of 1911-12 (Fig. 14), which scholars have associated with contemporaneous studies for the Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries (Ades, Cox, and Hopkins 68-69). The prospect that Duchamp was influenced by forms or mannequins was further investigated by Lebel, who sought to qualify an earlier theory proffered by Jean Reboul:

| Jean Reboul’s very persuasive hypothesis, according to which [the malic moulds] could have been suggested by the show window of an American dry-cleaner’s, can scarcely be proven chronologically, for the Malic Moulds antedate Duchamp’s trip to New York, but an ordinary Parisian cleaner’s would perhaps have been sufficient (qtd. in Joselit 139). |

click to enlarge

Figure 15

Page from the catalog

of the Manufacture Française d’Armes et Cycles de St. Etienne, 1913, cat. p. 53

Figure 16

Marcel Duchamp,

Once More to This Star, 1911

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Figure 17

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, 1912

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Figure 18

Marcel Duchamp,

Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries No. 1, 1913

© 2000 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

In a similar vein, Michel Sanouillet noted an affinity between the molds and “the sportswear presentation on invisible dummies” (53) found in a 1913 catalog from the company Manufacture Française d’Armes et Cycles de Saint-Etienne (Fig. 15).

Duchamp’s enigmatic drawing Once More to This Star of 1911 (Fig. 16) is generally considered an early formulation of the seminal Nude Descending a Staircase. However, the bizarre figure on the left in the drawing, commonly interpreted as exhibiting female characteristics, can also be perceived as a precursor of the molds. Lawrence D. Steefel, Jr. noted that the upper torso of this figure resembles “a prepuced cylindrical shaft, a ‘capped trunk’ topped by a bushy scrawl of graffiti-like linear squirls from the waist up” (25). Steefel’s description of this figure could very well be applied to the molds. The “cylindrical shaft” of the female figure’s body may very well anticipate the largely cylindrical “bodies” of the molds, and the “bushy scrawl of … linear squirls,” which can conceivably be interpreted as hair, could be the predecessor of the various hats of the molds.

The first appearance of the bachelors proper and the theme of the Glass is seen in Duchamp’s 1912 drawing The Bride Stripped Bare by the Bachelors (Fig. 17). These threatening figures in the 1912 drawing, however, are a far cry from the benign, diminutive bachelors in the Glass. In addition to robbing them of their sinister, pointed protuberances, Duchamp made this drawing the first and last instance in which the bachelors would directly confront the bride (D’Harnoncourt and McShine 262). The first description of the bachelors as they would appear in the Glass is found in The Green Box of 1934, the collection of Duchamp’s notes for the Glass, which spans from 1911 to 1920. It is in these notes that the bachelors are first described as the “Malic Molds,” and the “Cemetery of 8 uniforms or liveries” (Sanouillet and Peterson 51). The designation “Malic” has been interpreted as meaning mâle, or “male-ish,” rather than masculine (Tomkins 89), and as a pun on the word “phallic” (Golding 65).

The first drawing representing the molds as they would appear in the Glass, titled Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries No. 1 of 1913 (Fig. 18), shows the eight molds individually numbered and drawn in perspective. A key on the left identifies the uniforms, which are, from one to eight: a priest, a department-store delivery boy, a gendarme, a cuirassier, a policeman, an undertaker, a flunkey, and a busboy. Six months later, the number of molds became nine with the addition of the stationmaster. In an interview with Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp explained the transition from eight to nine molds, “At first I thought of eight and I thought, that’s not a multiple of three. It didn’t go with my idea of threes. I added one, which made nine” (48).

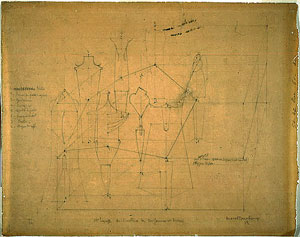

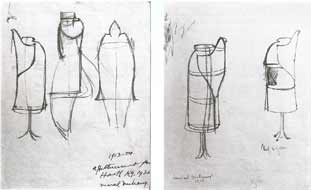

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Marcel Duchamp, Studies for the

Bachelors, 1913

© 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Figure 20

Marcel Duchamp, Cemetery of Uniforms

and Liveries No. 2, 1914

© 2000

Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Sketches for the stationmaster from 1913 (Fig. 19) show that Duchamp originally conceived the figure much like the dress form in his drawing Mid-Lent and Gustave Candel’s mother, with a cylindrical body atop a thin stand with four legs. While the exterior of the mold approximates the respective uniform it represents, the actual depiction of the uniform is invisible to the eye. As Duchamp explained, “you can’t see the actual form of the Policeman or the Bellboy or the Undertaker because each one of these precise forms of uniforms is inside its particular mold” (D’Harnoncourt and McShine 277). The Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, No. 2 of 1914 (Fig. 20), a blueprint rendered in reverse for transferring the image to the glass, shows the final realization of the molds just prior to their transition to glass. Of greater interest to this study, however, is not the final composition, but the first drawing of the Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries with only eight molds. Initially the number seems rather arbitrary. However, in light of Duchamp’s chess-related sketches and paintings from 1910 to 1912 and Tomkins’ assertion that the molds “resemble chessmen,” it follows that chess may have played a greater role in the conceptualization of the molds than has previously been considered.

One of the most significant developments in the social history of chess was the emergence of the chess moralities, which were allegorical sermons using the names and moves of the chessmen as the foundation for “ethical, moral, social, religious and political precepts” (Gizycki 23). Prior to the fifteenth century, several of the more conservative ecclesiastic establishments attempted to prohibit the playing of chess within the clergy, and these edicts often spread into the secular sphere as well. The Eastern Orthodox Church was especially zealous in its interdictions against chess, and members of the clergy known to indulge in the game were often castigated by those who abstained. One of the earliest documents containing a reference to chess to which an exact date can be assigned is a letter written by the eleventh-century Cardinal Petrus Damiani, Bishop of Ostia, who accused another bishop of “sporting away his evenings with the vanity of chess and so defiling with the pollution of a sacrilegious game the hand that offered up the body of the Lord” (Dennis and Wilkinson xx). On the whole, the Western Church was somewhat less impassioned about its proscriptions against chess, generally limiting its injunctions to the clergy and the knightly orders. Of the numerous decrees written in the twelfth, thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, perhaps the most well known is that of St. Bernard of Clairvaux, whose sanctions against the game for the Knights Templar were overturned in the fifteenth century (Murray, History 411). It is worthy of note that while chess was most explicitly forbidden within the clerical orders, the greater part of European chess literature from the Middle Ages was produced in churches and monasteries.

The repudiation of chess by the church was not wholly unfounded for several reasons. As indicated in Damiani’s diatribe, chess had strong associations with alea, an inclusive term used for all games of chance using dice, with or without a board (Murray, History 409). Indeed, a ninth-century variant of chess developed by the Muslims used dice, and written records suggest that this alternative format was popular in Europe during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries (Murray, History 410). The main attraction of involving dice in chess was that it sped up play; however, the introduction of chance into the game had an antipodal affect on the strategic element, and brought it dangerously close to gambling. In fact, the other aspect of chess that was most disturbing to the church was the regular involvement of stakes, which, for obvious reasons, was found intolerable. Despite the actions taken by the church, the spread of the game throughout Europe proved swift and unyielding, primarily due to its popularity with the aristocracy (Murray, History 428). In fact, according to Murray, “From the thirteenth to the fifteenth century, chess attained a popularity in Western Europe which has never been excelled, and probably never equaled at any later date” (History 428).

As the popularity of the game grew beyond the restrictive power of the church, the friars wisely chose to adapt chess to ecclesiastical purposes by writing the chess moralities, after which the game’s popularity rose to even greater heights. For the most part, the moralities were intended to provide moral instruction using the game as little more than a scaffold for religious precepts. The most famous of these moralities by far was written between 1275 and 1300 by the Dominican monk Jacobus de Cessolis, titled Liber de moribus Hominum et officiis Nobilum ac Popularium super ludo scacchorum (On the Customs of Men and Their Noble Actions with Reference to the Game of Chess). Arguably the most prominent book of its time, the number of existing manuscripts of Cessolis’s sermon indicates that it must have rivaled the Bible in popularity (Murray, History 537). Written in Latin, the sermon was translated into virtually every European language, often using texts that were themselves several generations away from the original text, which accounts for the wide variations one encounters from version to version. The most well known of these translations is the famed English printer William Caxton’s Game and Playe of the Chesse, which was published in Bruges in 1475, followed by a second illustrated edition printed in London in 1483. Caxton’s version, one of the earliest books to be printed in English, is a translation of a French adaptation of Cessolis’s manuscript written by the friar Jean de Vignay around the middle of the fourteenth century (Murray, History 547).

As indicated in the following passage from Hans and Siegfried Wichmann’s survey of the history of chess pieces, the individuated pawns served merely as vehicles for Cessolis’s narrative:

The pawns, which were largely non-representational, had no individual significance. The novel allegorical interpretation of the game in the spirit of the social order gave each piece a value in the general scheme and the pawns, too, now represented various trades and professions. The game thus presented a state based on philosophical and moral ideas, sanctioned by the church” (33).

Indeed, rarely in Cessolis’s exegeses are the pieces even mentioned. Perhaps the most common metaphorical use of the chess pieces was that of the game as an allegory of human life, which became a staple of the moralities. In addition to the obvious relationship between the game and medieval society, these authors recognized that after a piece was taken by an opponent it became obsolete, and thus all pieces, regardless of their rank on the board, were of equal stature after being removed. This aspect of the game made for a convenient analogy to the inevitability and utter finality of death for everyone regardless of one’s position in society, or, in Cessolis’s words (by way of Caxton), “For as well shall dye the ryche as the poure / deth maketh alle thynge lyke and putteth alle to an ende” (Caxton 80). In one of the final sermons, Cessolis imputed to the limited move of the pawn a symbolic meaning. For demonstrating “vertue and strengthe” by traversing the board one square at a time, the pawn is elevated to the status of queen (called pawn promotion) and receives “that thynge the other noble[s] fynde by dignyte” (Caxton 179), by which Cessolis undoubtedly meant divine right. Cessolis supported the possibility (albeit slight) of this kind of transcendence of the rigid stratification of medieval society through scripture, pointing out that David was a plebeian shepherd before he became king.

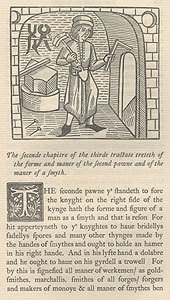

Figure 21

Book cover from a French book about chess, 15th century,

illustrated in Jerry Gizycki, A History of Chess,

London: Abbey Library, p. 20.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 22

- Figure 22

- oodcut of the Smith, illustrated

in William Caxton, The Game and Playe of

the Chesse, London:

Elliot Stock,

1883, p. 85 - Woodcut of the City Guard,

illus. in Caxton, p. 138

The pawns, which stood for the commonality, were subdivided into eight vocations: laborers and farmers, smiths, weavers and notaries, merchants, physicians, innkeepers, city guards, and ribalds and gamblers (Murray, Short History 34). Each pawn is clearly recognizable by the attributes of its trade, as seen in an illustration from the cover of a fifteenth-century French book on chess (Fig. 21), which is conveniently labeled (and, remarkably, includes the player or l’acteur in the upper right-hand corner). The placement of each vocation on the board was crucial, since the pawn had to be associated with the role of the more significant piece behind it. For instance, the smiths and city guards, as seen in two woodcuts from Caxton’s illustrated edition (Figs. 22 and 23), were placed in front of the knights because smiths were responsible for making bridles, saddles and spurs (Caxton 85), and the city guards received their military training from the knights as well (Caxton 139).

click images to enlarge

- Figure 24

- Figure 25

- Figure 26

- Figure 27

- Weaver and Notary, illus. in color in Karl S. Kramer, Bauern, Handwerker und Bürger

im Schachzabelbuch: Mittelalterliche Ständegliederung nach Jacobus de Cessolis, Munich: Deutscher Kunstverlag,

1995, p.26. - Weaver and Notary, illus. in color in Kramer, p. 27

- Physician, illus. in color in Kramer, p. 32.

- Physician, illus. in color in Kramer, p. 33

Regardless of the translation, the images of the various pawns are always similar because Cessolis included vivid descriptions of how each respective pawn was to be depicted. For example, the weaver and notary, as seen in an illustration from a German translation of 1456 (Fig. 24) and a depiction from a Latin transcription of 1460 (Fig. 25), “shall have a pair of scissors in his right hand and a knife in his left. At his belt shall be writing utensils and a pen behind his right ear” (Wichmann 34-35). These instructions were not always followed to the letter, however, as seen in an illustration of the physician from a 1407 German manuscript (Fig. 26), who holds the book in his left hand and the jar of medicine in his right rather than vice versa, as is correctly shown according to Cessolis’s instructions in a 1454 German translation of either Bavarian or Austrian origin (Fig. 27).

As with Duchamp’s Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries, Cessolis’s strict guidelines for illustrating the various pawns indicate that the figures, or, more specifically, the bodies of the figures, were of less importance than the attributes of the pawn’s respective profession. Moreover, like the molds, the pawns were always represented as male (as instructed by the text), and as a whole were meant to represent a specific class of people. While most of the professions of the allegorical pawns do not directly correspond with those of the molds, it makes sense that Duchamp would have updated the professions to better suit twentieth-century society.

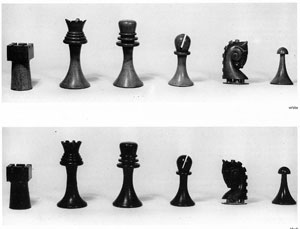

click to enlarge

Figure 28

Marcel Duchamp, Chessmen,

1918-19 © 2000 Succession Marcel

Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris

Linda Dalrymple Henderson has claimed that the inclusion of “a priest as the first of the sexually desirous Malic Molds” is an example of Duchamp’s “iconoclasm” (182). However, in a fifteenth-century German compilation of moralities called the Destructorium vitiorum, which includes an extended version of the Innocent Morality (so called due to its association with Pope Innocent III), the pawns represent “the poor workman or poor cleric or parish priest” (Murray, History 534). While I do not argue that the insertion of a priest (which, as indicated by the scribbled-out word preceding “prêtre” in Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries No. 1, was not Duchamp’s initial choice for the designation of the first mold) as a “sexually desirous” bachelor is in fact iconoclastic, I do contend that iconoclasm may not have been the sole inspiration for the inclusion of the priest. In fact, a more definitive statement of Duchamp’s iconoclasm – albeit a tongue in cheek one – was the omission of a cross at the top of the king from the chess set he designed and carved (with the exception of the knight) in Buenos Aires in 1918-19 (Fig. 28), an act he facetiously described to Arturo Schwarz as “my declaration of anticlericalism” (Schwarz 2:667).

If Duchamp’s Malic Molds were indeed inspired by pawns from chess history, it may not be the first instance in which Duchamp personified chess pieces in his art. Dario Gamboni observed that in Duchamp’s Portrait of Chess Players of 1911, the player on the left, a representation of Duchamp’s brother Raymond Duchamp-Villon, holds in his hand a chess pawn with strikingly anthropomorphic characteristics (Gamboni). This can be interpreted as a play on the French word for pawn “pion,” which also means “man” in reference to draughts or checkers, or the German “Bauer,” which can denote “peasant” as well as a chess pawn.

A crucial component of this study is identifying the sources through which Duchamp could have been introduced to the chess moralities, barring the possibility that he encountered them by word of mouth. One resource that has already been mentioned several times is Murray’s A History of Chess, published by the Clarendon Press in 1913, which, incidentally, was the same year in which Duchamp executed his first plans for The Cemetery of Uniforms and Liveries. Described in The Oxford Companion to Chess as “perhaps the most important chess book in English” (Hooper and Whyld 265), Murray’s 900-page History, the culmination of fourteen years of research, is an exhaustive exploration of the development of the game from its beginnings in the East to modern chess. Murray’s massive undertaking included learning Arabic in order to consult essential manuscripts, and studying the major collections of chess artifacts and literature, most notably the collection of John Griswold White of Cleveland, Ohio, the largest chess library in the world. Considering Duchamp’s already highly developed interest in chess at this time, it is conceivable that he would not only have known of Murray’s valuable study, but perhaps consulted it as well.

Pending conclusive evidence that Duchamp knew of Murray’s History, there remains a significant resource of books in several languages on the history of chess and chess literature with which Duchamp may have been familiar. Murray’s book was largely based on the work of the Dutch chess historian Antonius van der Linde, who published several books on the history of chess literature in Berlin at the end of the nineteenth century (Hooper and Whyld 219). In Paris, Librarie Hachette published Henry René d’Allemagne’s Récréations et Passe-Temps in 1905, which also includes a description of the chess moralities. Supplementing this short list of secondary sources for Cessolis’s sermon is the extensive number of primary sources, of which there are at least eighty versions of the Latin text alone (Murray, History 537), not to mention the profusion of existing French, English and German translations. Furthermore, an exact reprint of Caxton’s Game and Playe of the Chesse, including the woodcut illustrations, was printed by Elliot Stock Publishers in London in 1883, which made a formerly rare text readily available to the public and, more importantly, Marcel Duchamp.

Work Cited

1. Ades, Dawn, Neil Cox, and David Hopkins. Marcel

Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson, 1999.

2. Arman, Yves. Marcel Duchamp Plays and Wins. New York: Galerie Yves Arman, 1984.

3. Cabanne, Pierre. Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp.

Trans. Ron Padgett. New York: Da Capo, 1987.

4. Caxton, William. Game and Playe of the Chesse. 1474. London: Elliot Stock, 1883.

5. D’Allemagne, Henry René. Récréations et Passe-Temps. Paris: Librarie Hachette, 1905.

6. D’Harnoncourt, Anne and Kynaston McShine, eds. Marcel Duchamp. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1973.

7. Dennis, Jessie McNab and Charles K. Wilkinson. Chess: East and West, Past and Present. Greenwich, Conn.: New York Graphic

Society, 1968.

8. Gamboni, Dario. Lecture. Spring 1999.

9. Gizycki, Jerry. A History of Chess. English ed. B. H. Wood. London: Abbey Library, 1972.

10. Golding, John. Marcel Duchamp: The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. New York: Viking, 1972.

11. Henderson, Linda Dalrymple. Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works. Princeton,

NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

12. Hopper, David and Kenneth Whyld. The Oxford Companion to Chess. New York: Oxford University Press, 1984.

13. Joselit, David. Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp (1910-1941). Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1998.

14. Keene, Raymond. “Principal Chess Happenings in the Life of Marcel Duchamp.” Duchamp: Passim. Ed. Anthony Hill. St. Leonards, Australia: Gordon and Breach Arts International; Langhorne, Pa.: International Publishers Distributor, 1994, 125.

15. Lebel, Robert. Marcel Duchamp. Trans. George Hamilton. New York: Grove Press, 1959.

16. Murray, H. J. R. A History of Chess. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1913.

17. —. A Short History of Chess. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1963.

18. Naumann, Francis M. “Affectueusement, Marcel: Ten Letters from Marcel Duchamp to Suzanne Duchamp and Jean Crotti.” Archives of American Art Journal 29.4 (1982): 3-19.

19. Sanouillet, Michel. “Marcel Duchamp and the French Intellectual Tradition.” Marcel Duchamp. Eds. Anne D’Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine. 47-55.

20. Sanouillet, Michel and Elmer Peterson, eds. The Essential Writings of Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson, 1973.

21. Schwarz, Arturo. The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp.3rd ed. 2 vols. New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997.

22. Steefel, Lawrence D., Jr. “Marcel Duchamp’s Encoreà cet Astre: A New Look.” Art Journal, 36.1 (1976): 23-30.

23. Tomkins, Calvin. The World of Marcel Duchamp, 1887-1968. New York: time-Life, 1974.

24. Wichmann, Hans and Siegfried. Chess: The Story of Chesspieces from Antiquity to Modern Times. Trans. Cornelia Brookfield and Claudia Rosoux. New York: Crown, 1964.