| Man is the symbol-using (symbol-making, symbol-misusing) animal inventor of the negative (or moralized by the negative) separated from his natural condition by instruments of his own making goaded by the spirit of hierarchy (or moved by the sense of order) and rotten with perfection (Burke, On Symbols, 70). |

This definition is central to Kenneth Burke’s theory of rhetoric. To Burke, words are symbols; they are utterances, manufactured by “Man” to signify those things which they represent. Words are an easy target for study. Although somewhat indeterminate in meaning, the mere presence of them denotes human authorship. Whether written or spoken, a word is a deliberate act, brought into being for the express purpose of expressing. Words are written down to transmit ideas. For example, I could describe the act of milking a goat for the purpose of instruction without including an actual goat (or myself) in the text. Words are small, convenient packages for large ideas. But as a result of indeterminacy, error, ignorance, inadequacy and/or inaccuracy, words can only be symbols, they can never be that which they represent. In other words, the word “goat” cannot and will not be a goat. Thus, words function as a heuristic, they are symbols, which we must inform with our own understanding of what they mean. The word “goat” can make one person think of a petting zoo animal, another person think of a drawing of a goat from a storybook, while it will always make me think of my pet goat, “Maybell.” Each reader generates his/her own idea based on what the words say, and the skillful rhetorician can guide the reader through this generation so that he/she arrives at a desired idea. Since this is how persuasion is accomplished, we must also consider non-verbal symbols for their heuristic qualities— for their ability to arouse thoughts.

This non-verbal “text” is as powerful as it is elusive. In the verbal text, specific words are available for scrutiny. The aid of a dictionary can be enlisted to help determine meaning. But objects, while they may be selected, placed, framed, or altered deliberately are “inert.” They do not “say” anything in the sense that this paper does. Inanimate objects, because of their lack of words, invite us to identify them and identify with them. Objects, particularly manufactured ones, are part of our world of things. We are used to using them, and like inkblots in a Rorschach test, they passively accept our ideas, emotions, and judgements.

Objects then have enormous rhetorical potential, based on Burke’s idea that identification is the key to persuasion:

As for the relation between “identification” and “persuasion”: we might well keep it in mind that a speaker persuades an audience by the use of stylistic identifications; his act of persuasion may be for the purpose of causing the audience to identify itself with the speaker’s interests; and the speaker draws on identification of interests to establish a rapport between himself and his audience. So, there is no chance of keeping apart the meanings of persuasion, identification (“consubstantiality”) and communication (the nature of rhetoric as “addressed”)(Burke, On Symbols, 191).

When a person encounters an object, whether it is pondered or not, the mind acts upon it. Like a verbal text, it is “read,” but in a non-linear fashion. Instead, several different features may be observed at once, and immediately the object is recognized or not recognized, its meaning is relative to the viewer’s experience. In other words, it is identified as something familiar or unfamiliar, until it is identified otherwise. The key word is identification, the verbal text may contain words that the audience cannot translate, understand, or care about, and therefore fail to identify with. But the visual text is available for all who can see it. It exists in a language that the mind can understand easily and quickly, and it places the object in closer proximity to the life of the viewer. A picture of a goat, a stuffed goat, or the goat itself is more goat-like than the word “goat,” because it more closely resembles the tangible nature of our own animal existence. And no matter how the object appears, it always appears in the context of sensual experience. When something is seen, no matter how foreign, the image of that something can be used to symbolize that something. Alien words do not mean anything until we learn what thing they represent. In using alien terms, the rhetoricist can sever the “rapport” with the audience. Alien objects, on the other hand, provoke curiosity, strengthening the rapport. I can say “minkiki” and it seems nonsensical, but if I were to produce a minkiki, no matter how absurd it might look, its very existence would testify to its reality. Visual symbols are interesting because they carry more information than words, and in this way the viewer can partake of them more selfishly. He/she can dwell on the things they like and, since there are no words, he/she can supply the words that are interesting and appealing. Its mere presence calls the viewer to identify it. Thus a “speaker” can use non-verbal methods to establish the Burkeian notion of “consubstantiality.”

To effectively utilize non-verbal symbols to provoke a specific action would require a great deal of control. While objects can easily establish a rapport, to use this rapport to provoke a specific action is extremely challenging. As with the Rorschach test, people can see the same images, but have different ideas about what they might mean. In contrast to words, objects are much more complex; their function as a heuristic is dizzying, even overwhelming. Burke’s “Terministic Screens” which “direct attention to some channels rather than others,” become problematic in such a context because a visual cue can say so many things all at once (Burke, On Symbols, 115).

Marcel Duchamp is an artist who has managed to provoke specific reactions quite effectively. While he is known for his place in the pantheon of Fine Arts, his real skill is his ability to persuade rather than his ability to render aesthetically beautiful objects or arouse the world with his passion. His “readymades” are rhetorical objects; they are his “texts.” And by viewing them in light of Kenneth Burke’s theories, with which they bear a natural affinity, I hope to illuminate Duchamp’s rhetorical methods while analyzing some of Burke’s key concepts.

***

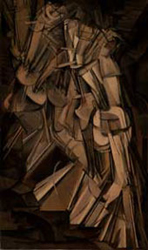

Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) began his artistic career in France, but it was in the United States that he became a sensation. His infamous Nude Descending a Staircase (Fig. 1) made its American debut at the Armory Show (1913) along with three other works, Sad Young Man on a Train (Fig. 2), Portrait of Chess Players (Fig. 3), and The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (Fig. 4); establishing Duchamp as an instant celebrity. While all four pieces sold, Duchamp’s reception was marked by scorn, ridicule, and incredulity. Thousands lined up to get a glimpse of the Nude, articles bashed its artistic value, and his work was rejected by the Cubist School with whom it was identified. He ultimately abandoned what he called “retinal” art, which is purely visual, in favor of “olfactory” (1)painting, which relied on the intellectual process for its aesthetic value (Paz 3). It was with this new attitude in mind that he began to craft his “readymades.”(2)

click images to enlarge

- Figure 1

- Figure 2

- Marcel Duchamp, Nude Descending

a Staircase, No. 2, 1912 - Marcel Duchamp, Sad Young

Man on a Train, 1911

click images to enlarge

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Marcel Duchamp, Portrait

of Chess Players,1911 - Marcel Duchamp, The King

and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, 1912

The “readymades” are mass-produced items which Duchamp selected, titled, signed, displayed, and, in some situations, altered or “aided.” In the short essay “Apropos of ‘Readymades,'” Duchamp describes his method of selection: “THIS CHOICE WAS BASED ON A REACTION OF VISUAL INDIFFERENCE WITH AT THE SAME TIME TOTAL ABSENCE OF GOOD OR BAD TASTE…IN FACT A COMPLETE ANESTHESIA.” In other words, Duchamp was careful to choose commonplace objects with no meaning to him whatsoever. By signing them with his name, he was able to transform them into art. Some of the meaning of this random process of selection has been lost. In fact, the word “random” has entered the popular vocabulary as a synonym for “cool” and “weird.”(3) But when considered in their original context, the art world of the early 1900s, the “readymades” must have appeared utterly absurd. These pieces, in all their simplicity, are surprisingly complex in the moves they require of the unsuspecting mind.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp,

Fountain, 1917/64

Although they all serve the same rhetorical purpose to me, Fountain is the most interesting of the “readymades.” Submitted under the pseudonym Richard Mutt to a 1917 show sponsored by the Society of Independent Artists (of which Duchamp was a member and founder), and which claimed to welcome the work of “any artist paying six dollars,” the piece was rejected on the grounds that it was “immoral” and guilty of “plagiarism” (Duchamp 817). Duchamp’s Fountain is nothing more than a urinal signed “R. Mutt” and named “Fountain.” (Fig. 5) The immediate response to the piece of plumbing was negative; it was perceived as an insult. But further contemplation brings a number of problems to bear.

To approach a urinal in the context of an art exhibit is definitely both strange and estranging. I remember when I first discovered that a toilet could be considered art. I was shocked and confused, considering that my initial understanding of art was bound up in notions of beauty and representational rendering. But once the shock gives way, the implications arouse thought. To a male viewer in a museum, a urinal is an easily recognizable item, an item that probably could be found at another location in that very same museum. This ability to “identify” the item lends itself to Burke’s “identification.” Rather than identify with the artist, who has no voice and is not physically present, the viewer can identify with the object or the “agency.” The object is a “commonplace.” Like Aristotle’s topics it is a common ground, a language which even the illiterate can understand (Burke, A Rhetoric,56).

A urinal has a specific use when it is placed in the bathroom, but outside of the bathroom it confounds. It invites the male viewer to participate in a strange way. Traditional high art, the nude especially, is often criticized for being for a male audience, and this piece calls attention to that. But unlike nudes, which are often criticized for seeking to engage the male viewer with sexual imagery, this seeks to do so without it. A urinal requires the male to instead expose himself and to have another type of relation altogether. A urinal is a place to urinate while art is something to adore. To pee on art would be a sacrilege, and this is what Duchamp has done by creating his peon art.

The title of the work compounds the problem. Duchamp chooses to call it Fountain. This title in its simplicity has the effect of conjuring up essentials. Similar to my asking readers to think about “goats,” Duchamp is asking his audience to think about fountains. The word may cause each person to think about a particular fountain, but when used to name a urinal, it creates a dialectic. What makes a fountain a fountain and a non-fountain a non-fountain? The result is an essentialization, or the recognition of an ideal fountain which bears the qualities of “Fountainness.” This “perspective by incongruity” is gained by placing things in different, seemingly opposite, contexts (Hyman, 21). Once the concept of Fountain is arrived at, then the next step is to determine how Fountain is a fountain.

To fulfill the Fountain’s Fountainness the viewer must first fill the fountain. (Who ever heard of a fountain with no water?) Fill the fountain with abstract notions of an idealized Fountain or fill it with urine, either way the viewer becomes the mechanism by which Fountain can function. Here scatology and eschatology overlap (Burke, A Rhetoric, 308)(4)Through the simple act of placing a urinal (agency) in a particular scene, Duchamp (agent) has created (purpose) a spiraling mass of artistic criticism that goes high and low, and ultimately asks the viewer to transcend previous notions of what art is.(5) The actual process which I have described is what Burke would call a “Watershed moment” (Warnock, 272).(6)

As you can see, the discussion requires a proliferation of terms, or symbols. What I have been calling a urinal, in a sense, is not even a urinal at all. It does not function, nobody would use it; and as useful and common as a urinal can be, when it is sculpted into a Fountain, it becomes useless and unique. Similarly, Fountain is not a fountain at all. It has no water in it and it is just a urinal. Even Marcel Duchamp’s role is called into question as the actor in this drama. He signed it as an artist, but he signed the wrong name. He did not make it in any conventional sense of the word. It is art because people view Duchamp as an artist. The more one looks at Fountain as art, the less it resembles it. And the less it resembles art, the more it looks like it.

I am not deconstructing Duchamp’s work. I am simply describing the way it functions. While deconstruction as a critical act relies on the inherent indeterminacy of meaning, Duchamp’s work uses indeterminacy as a rhetorical device and does so with determination. He crafts his “readymade” texts with a specific purpose in mind, and in that way I think he deserves to be studied as a skilled persuader.

Duchamp’s work lends itself to the study of Burke’s theories of rhetoric because Duchamp was very interested in language, signs, and symbols. Duchamp used signs that require his audience to engage in the process “No-ing” and “Knowing” (Warnock, 272). While “Knowing” requires an intuitive apprehension of truth; “No-ing” requires the audience to travel around the subject, negating that which it is not, and through the process of elimination, arriving at the truth. Fountain requires the audience to engage it in this way. The piece does it so well that its meaning cannot be nailed down. It is an action, perpetually shifting in meaning as each new vantage point is reached.

Duchamp’s work continually calls the audience to transcend meaning. Doing so, it approaches Burke’s pure persuasion:

The dialectical transcending of reality through symbols is at the roots of this mystery, at least so far as naturalistic motives are concerned. It culminates in pure persuasion, absolute communication, beseechment for itself alone, praise and blame so universalized as to have no assignable physical object (Burke, A Rhetoric, 275).

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors, Even, 1915-23

It should be noted that Duchamp frequently gave his works away rather than sell them (Paz, 89). As well, “In 1923 Duchamp abandoned definitively the painting of the Large Glass. (Fig. 6) From then on his activity has been isolated and discontinuous. His only permanent occupation has been chess” (Paz, 87). Based on these facts, it seems as though Duchamp was interested in persuading as an end in itself. He did not seek out fame or wealth; he was a creative person who liked to play games. Duchamp’s works are rhetorical actions which cause the viewer to act and transcend, while always maintaining a playfulness which mirrors Burke’s own attitude and approaches the Burkean notion of pure persuasion.

Notes

1. Paz discusses Duchamp’s term “Olfactory Art” for the “negation of painting,” or painting with ideas

1. Paz discusses Duchamp’s term “Olfactory Art” for the “negation of painting,” or painting with ideas

rather than pictures. He uses the word “olfactory” to draw attention to the fact that it relies on the

intellectual process rather than the eyes and to bring to mind its “smell of turpentine.”

2.For more information please see Robert Lebel, “1913: Triumph at the Armory Show and Rejection

2.For more information please see Robert Lebel, “1913: Triumph at the Armory Show and Rejection

of ‘Retinal’ Art,” Marcel Duchamp (New York: Grove Press, 1959) 25-35.

3. For example, “Oh my God, Jenny! Did you see the Beck interview n MTV last night. He is so

3. For example, “Oh my God, Jenny! Did you see the Beck interview n MTV last night. He is so

totally random.”

4. From Burke on “fecal idealism” in ancient Egypt.

4. From Burke on “fecal idealism” in ancient Egypt.

5. For a discussion of “Act, Agent, Agency, Scene, and Purpose,” see Burke’s “The Five Master Terms.”

5. For a discussion of “Act, Agent, Agency, Scene, and Purpose,” see Burke’s “The Five Master Terms.”

6. The “Watershed Moment” is one in which the audience transcends the division between itself and the text, but this transcendence leads to further

6. The “Watershed Moment” is one in which the audience transcends the division between itself and the text, but this transcendence leads to further

problems.

Bibliographies

Blankenship, Jane, Edward Murphy, and Marie

Rosenwasser. “Pivotal Terms in the Early Works of Kenneth Burke.” Brummett,

71-90.

Booth, Wayne C. “Kenneth Burke’s Comedy:

The Multiplication of Perspectives.” Brummett, 243-270.

Brummett, Barry, ed. Landmark Essays

On Kenneth Burke. Davis: Hermagoras Press, 1993.

Burke, Kenneth. A Rhetoric of Motives.

Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

– – – . On Symbols and Society.

Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1989.

– – – . “The Five Master Terms.” Landmark

Essays on Rhetorical Invention in Writing. Davis: Hermagoras Press,

1994. 1-12.

Comprone, Joseph. “Kenneth Burke and the

Teaching of Writing.” College Composition and Communication 29

(December 1978): 336-40.

Day, Dennis G. “Persuasion and the Concept

of Identification.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 46 (October 1960):

270-73.

Duchamp, Marcel. “Apropos of ‘Readymades.’”

Stiles and Selz, 819-820.

– – – . “The Creative Act.” Stiles and

Selz, 818-819.

– – – . “The Richard Mutt Case.” Stiles

and Selz, 817.

Duncan, Hugh Dalziel. “‘Introduction’ to

Symbols in Society.” Brummett, 179-198.

Griffin, Leland M. “When Dreams Collide:

Rhetorical Trajectories in the Assasination of President Kennedy.” Quarterly

Journal of Speech 70 (May 1984): 111-131.

Hochmuth Nichols, Marie. “Kenneth Burke

and the ‘New Rhetoric.’” Brummett 3-18.

Hyman, Stanley Edgar. “Kenneth Burke and

the Criticism of Symbolic Action.” Brummett 19-62.

Keith, Philip M. “Burkeian Invention: Two

Contrasting Views: Burkeian Invention, from Pentad to Dialectic.” Rhetoric

Society Quarterly 9 (Summer 1979): 137-41.

Lebel, Robert. Marcel Duchamp. New

York: Grove Press, 1959.

Nemerov, Howard. “Everything, Preferably

All At Once.” Brummett, 63-70.

Paz, Octavio. Marcel Duchamp: Appearance

Stripped Bare. New York: Viking Penguin Inc., 1978.

Rosenfeld, Lawrence B. “Set Theory: Key

to the Understanding of Kenneth Burke’s Use of the Term Identification.”

Western Speech 33 (Summer 1969): 175-83.

Rueckert, William H. “Towards a Better

Life Through Symbolic Action.” Brummett 155-178.

Stiles, Kristine and Peter Selz , eds.

Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art: A Sourcebook of Artists’

Writings. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996.

Tomkins, Calvin. The World of Marcel

Duchamp. New York: Time Inc., 1966.

Warnock, Tilly. “Reading Kenneth Burke:

Ways In, Ways Out, Ways Roundabout.” College English 48 (January

1986): 262-75.

Figs. 1-6

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.