Dagblad Trouw (Dutch National Newspaper), Saturday February 24, 2001

click to enlarge

Figure 1

J.S.G. Boggs

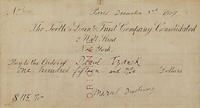

When Marcel Duchamp was asked why he stopped painting at an early age, his answer was: “I don’t want to copy myself, like all the others. Do you think they enjoy painting the same thing fifty or a hundred times? Not at all, they no longer make pictures; they make checks.” Now that the art world revolves around more money than ever before, and the commodification of art has reached neurotic levels, Duchamp’s statement is hard to disagree with. But what if Duchamp had met J.S.G. Boggs (Fig. 1), an artist who actually makes bills, checks, and recently coins? As a moneymaker, Boggs seems to be the epitome of the commercial, repetitive artist Duchamp had in mind. Nevertheless, my guess is that he would take an interest in Boggs’ bills. In fact, Duchamp made some checks himself–to pay for the services of his Parisian dentist Tzanck in 1919, to help his friend John Cage raise funds for the advancement of performance art, and to satisfy a personal fan’s request for a signature at a New York gallery in 1965.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Tzanck Check, 1919

Figure 3

J.S.G. Boggs, $1 Fun

Bill, date unknown

The parallels between the Tzanck Check (Fig. 2) in particular and Boggs’ bills go further than the laborious production process that these painstakingly precise copies spring from. Like Duchamp, Boggs documents conceptions of value that inform the art world, and investigates how worth comes into being (even though enlightenment about these matters can hardly be expected). Furthermore, he plays with economic systems as if they were children’s toys, like Duchamp did with the institutions of the art world. And if you still cherish any illusions about the absolute value of money, or art, for that matter, start thinking about Boggs’ bills.(Fig. 3)

1. In the beginning

Boggs made his first bill in 1984–unintentionally so, and without the faintest notion of the never-ending lawsuits, the media attention, and the extraordinary prices that his bills would generate in the years to follow. At the time, Boggs was sitting in a Chicago bar, making a complex drawing on a napkin that depicted the number one. Numbers were an obsession of the artist at that time; they still are, in fact. A waitress of the bar instantly developed a liking for the drawing. It reminded her of a dollar bill, and as much as she liked it, she asked Boggs to pay his 90-cent bill with it. The waitress also insisted that Boggs accept a dime in change. With a fine pen, he has been copying bills ever since.

click to enlarge

Figure 4

J.S.G. Boggs’ version

of Sacagawea Dollar

(front and back), 2001

Figure 5

Original $1

Sacagawea Coin

Recently, Boggs commemorated that original event silently: for his latest project, which started right at the official beginning of the twenty-first millennium, Boggs had 100,000 Sacagawea dollars fabricated (Fig. 4) by an organization specializing in educational materials regarding Currency. Boggs’ own version of the new one-dollar coin is slightly larger than the original, (Fig. 5) and is pressed out of plastic. The coins have six different mintmarks–J, S, G, B, M21 and CH 84. The currency artist financed their fabrication with a 5,000-dollar bill that he self-evidently drew himself.

In the seventeen years that lie in between, Boggs has managed to spend his bills in several million dollars worth of economic transactions. If Duchamp paid for his dentist, Boggs paid for a Yamaha motorbike, for countless bills in bars, restaurants and hotels, for airplane tickets, artworks, rare old bills, and many other goods. In Portland, he bought a Hamburger with a 1,000-dollar bill, and received 997 real dollars in exchange. In the first months of this year he spent over 6,000 of his new plastic Sacagawea coins, among which 1,300 were exchanged for five ounces of gold bullion. All these transactions have elements of ordinary purchases, of barter transactions of an original artwork against a mass produced consumer good, and of artistic performances that are only slightly relevant to economics.

2. After Boggs

click to enlarge

Figure 6

J.S.G. Boggs,

Swiss 100 Francs

bill, late 1980s

Figure 7

J.S.G Boggs,

$10 FUNback, 1997

Is Boggs a counterfeiter–albeit a very successful one? No. A superficial glance is sufficient to distinguish Boggs’ bills from the original. The backside is left blank and Boggs adds some puns to the front. Instead of “In God we trust,” an orange fifty dollar bill reads “Red gold we trust”; a Swiss 100 Francs bill from the late 1980s (Fig. 6) depicts his self-portrait as an “angry young man”; on a ten dollar bill, the building of the treasury is replaced by the Supreme Court, (Fig. 7) accompanied by the text “Please give me a fair trial.” Furthermore, all bills are signed by Boggs himself, sometimes as “treasurer of art,” on other occasions as “secretary of measury.”

The problem is that Boggs does draw his bills life size and in the actual colors of the original, which resulted in legal trouble on a number of occasions. In Australia, a court case was dismissed almost right away, after which Boggs received $20,000 in damages. In England, Scotland Yard arrested him and confiscated his work while he was installing a gallery exhibition. Again, he was acquitted of the charges. To celebrate his victory, Boggs announced that he would live on self-made money for an entire year. In the United States, however, his trials have caused him more lasting trouble. When Boggs was spending a year as a fellow at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, the Secret Service raided his apartment and studio and confiscated approximately 1,300 objects.

Although the U.S. Attorney did not press charges, Boggs has been involved in a legal battle for almost an entire decade now to get all of his belongings back. Paradoxically, one of the few counterfeited bills that he owned (but did not make himself) was returned, but the Secret Service kept the clownish 1,000,000 dollar bill available by order from the Internet. Incidentally, the trial will result in the largest transaction in Boggs’ career as a money artist, since he plans to pay for the lawyer’s fee, which amounts to around a million dollars, with 100,000 dollar bills. Bogg’s lawyers, who are most sympathetic to his case, have actually promised to accept these bills as a valid means of payment.

Unlike the Secret Service, the contemporary art world does value Boggs’ bills. Museums like the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the British Museum in London own copies of his work. Private collectors underscore their cultural value by offering Boggs considerable sums for a hint about when and where he spent his bills; subsequently, they pay large sums to acquire a bill from the shopkeepers who were brave enough to accept Boggs’ money. Like Duchamp, whose signature was sought after in the 1960s as if he was a celebrity, Boggs has a large following of people eager to obtain his signature. Personal fans have to pay him a small fee for an autograph, while a signature is only within reach for mavericks who are willing to spend $2,000 or more. No need for Boggs to complain about financial or artistic rewards.

In short, Boggs’ bills generate extreme, albeit contradictory, reactions. I wonder, however, if the legal trouble and the arti-financial success that his work generates are really that distinct. Note, for instance, that both the legal apparatus and the army of collectors ultimately intend to take his work out of circulation. And when it comes to their sense of humor, my expectations of a collector who pays $50,000 or more for a Boggs bill are no higher than that of a prosecutor who wants to stop Boggs from making the bills in the first place. Both try to “capture” Boggs, with either money or the law as their instrument– in vain, I presume.

3. No land for money

I met Boggs when he was in Amsterdam in early February for a performance in the “West Indisch Huis.” In the seventeenth century, the “West Indisch Huis” was built for the West Indische Compagnie, which enjoyed a monopoly on trade between America, West Africa and Holland. Currently the building is the home base of the John Adams Institute, which organizes lectures by American intellectuals, writers and artists. The title of Boggs’ performance there was I’ll take Manhattan.

At the start of the performance Boggs, 44, who has wild gray-blond hair that nearly reaches his shoulders, takes a digital picture of the audience, while a bag filled with orange plastic Sacagawea coins lies between his legs. Then he recounts the story of Peter Minuit, governor of the West Indische Compagnie, who sailed to the island of Manhattan. He was welcomed in May 1626, 375 years ago today, by an Indian clan. Soon after his arrival, Minuit bought the island from the Indians for trinkets worth sixty guilders. Among those trinkets were “wampum,” the Indian word for bead money, which had not only monetary but also cultural value for many clans–“wampum” was a means of transmitting the history of the clan from generation to generation. The Dutch, however, did not have history but money on their mind, which induced them to create their own “wampum” in order to deal with the Indians. Unknowingly, the Indians responded appropriately to the sly and sacrilegious offer of the Dutch by accepting the trinkets, but since they lacked a conception of land ownership, the Indians must have conceived of the transaction as some foreign ritual. Come to think of it, no land was exchanged for any money on that May Day in 1626.

The story of Minuit and the Indians is a perfect pre-figuration of Boggs own work; Minuit paid, just like Boggs, with improvised money, and probably needed a good share of rhetoric to do so. The color of Boggs’ Sacagawea coins is the same as the family name of the Dutch royal family: Orange. In fact, many of the first Dutch settlers on Manhattan used to live north of the island in Fortress Orange (the present Albany), and after the Dutch re-conquered Manhattan from the English in the second half of the seventeenth century, they renamed it New Orange.

Here is another parallel: the acquisition of Manhattan by the Dutch is listed in American history books for $24, mistakenly so, since the nineteenth century American historian who came up with the figure used the exchange rate of his own time rather than some seventeenth century equivalent. However, the exchange rate he used (60/24) is almost exactly the same as the present exchange rate of the Dutch guilder against the American dollar. Is there a meaning to all these parallels–synchronicities, as Boggs calls them? “I have no answers, just questions,” he says as he concludes his performance. It is the child in Boggs, who never seems to have deserted him, who needs these exercises in confusion.

4. Indecent proposal

When Boggs talks about his work, it is with great enthusiasm, cheer and wonder. However, when talking about the lawsuits, the tenderness in his eyes makes way for a furious look. Although Boggs seems flattered with the artistic and financial success of his endeavor, he does not strike me as particularly “money” oriented. Boggs admits that the material form of money is what fascinates him–the fact that it functions as a visual icon of society in a way that electronic money does not. But more than just a copier of money, he is a performance artist. When a collector recently offered to buy all his remaining coins for $100,000, Boggs refused. The golden rule is that he only parts with his money in real economic exchanges. He does not sell his work, in other words, he only “transacts” it.

“Do you think they will accept Boggs money here,” he asks in an old Amsterdam bar. Boggs insists that I will not intervene during the transaction, and promptly walks to the bar with a gentle smile on his face. Then he explains to the barkeeper with a charming voice: “Hi, I am an artist; I make my own money, and I try to spend it in real transactions. Today I would like to spend my money with you. These coins represent the value of a dollar. Would you accept four of them in exchange for two beer[s]?”

The lady looks puzzled and doubts if she should accept his offer. Before she can answer, however, her husband intervenes: “Paying with fake money is impossible,” he says aggressively, “is playing a trick” [in Dutch the husband used the word “kunstenmakerij,” which means both “making art,” and “playing a trick”]. Unsolicited, the barkeeper continues that he has been making his own living for thirty-five years, and urges Boggs to support himself with honest means as well. The next day, many refusals of his coins will follow, even at the coin shops located behind Dam Square. There is a striking pattern in the responses that his proposal evokes. Out of disbelief, men react irritated, while women often start giggling — an indication for social scientists that some taboo is being violated. Never does Boggs mention that the deal he is offering them is an offer nobody can refuse — after all, even the coins are worth much more than their face value on the resale market for Boggs’ work.

5. Resisting uniformity

By fabricating his own money, Boggs takes us back to a time when money was far from uniform. That time is not as far behind us as we tend to think. Until the nineteenth century, and in some countries up until the early twentieth century, a hodgepodge of different coins and bills were in circulation. In the United States, for instance, the dollar as we know it was only standardized in 1928. Until that time, almost any bank could issue its own bills. The Central Banks that were established in the nineteenth century were supposed to monitor the circulation of currencies and to create order in the chaotic monetary traffic of those days. As a result, the uniformity of money increased rapidly around the turn of the century, while issuing money was monopolized by the state in many Western European countries.

Around the same time, the German sociologist Georg Simmel wrote in his magnum opus Die Philosophie des Geldes that money is ultimately a destructive force. Money, that colorless and indifferent equivalent, would cover the world with an “evenly flat and gray tone,” Simmel wrote. Money reduced the diversity of goods and transactions to a common, uniform denominator. It even put pressure on relationships, Simmel argued, since social interaction was increasingly transformed into economic exchange.

In a late response to Simmel, the American sociologist Viviana Zelizer showed in The Social Meaning of Money (1994) that people do manage to resist the destructive power of money. In the second half of the nineteenth century, when monetary traffic was becoming standardized rapidly, many households started creating what Zelizer calls domestic currencies. They earmarked money for specific goals and named them Christmas money, drinking money, vacation money, etc. Moreover, these households established a direct link between the way money was earned and the appropriate spending of it. Thus, they partially nullified the alleged uniformity of money.

Currently, an area of tension is emerging comparable to that in the nineteenth century. This tension is exactly what provides Boggs’ art with the necessary ammunition. On the one hand, the uniformity of money has entered an era of renaissance due to the introduction of the EURO in the European Union, no less than eleven different currencies will disappear at once on January 1, 2002. Because of the increasing use of credit cards and payment by means of a PIN code, money is on its way to becoming extinct in its material form of bills and coins. In the global economy, money can only be spotted as changing numbers on computer displays in anonymous offices. “You see?” Simmel mumbles posthumously.

At the same time, however, a widespread and multifaceted resistance against this ongoing standardization of monetary traffic is emerging. Look at the new republics that came into being after the collapse of the Soviet Union and the crisis in the Balkans. One of the first political acts in these countries is the introduction of their own currency, which serves as a symbol of national unity. As inhabitants of a small country, the Danish population had good reasons to vote against the introduction of the EURO in a public referendum that was organized last fall. And on the Internet, where you would expect the ultimate triumph of money’s uniformity, new electronic currencies like e-gold are coming into being. Finally, it is remarkable that in the last decade, local currencies have been established in a number of places, like the British LETS (Local Exchange and Trading Schemes), Ithaca money in the American college town, or Noppes in Amsterdam. Like Boggs, many citizens refuse to reconcile themselves with the uniformity of money.

6. The Fragility of Money

All of these manifestations of resistance – Boggs’ bills in the first place — emphasize the conventional nature of money. If a businessman remarks that Boggs’ money is not real, Boggs acts surprised. Why would it be less real than the money we spend in everyday life? With a smile he replies that it costs the Central Bank only a few cents to print the bills we use, whereas Boggs himself has to put many hours into making his own money. It is a reversal of Duchamp’s institutional critique, addressing the economy rather than the art world. Whereas people demand originals rather than mass produced objects inside the walls of cultural institutions, Boggs’ original work is not accepted in the economic realm as a stand-in for the ready-made bills of modern Central Banks.

Thus Boggs forces people to come to terms with the fragile basis of money, with the fact that money lacks a solid, material basis. It solely derives its value from agreement—a widespread agreement, for that matter, but certainly not more than that. Many people still think that we can exchange our paper bills for gold at the Central Bank in a case of emergency, but that possibility was abolished in most countries in the first half of the 20th century. Given the conventional basis of money, it is easy to understand why objects as diverse as pearls, horse blankets, beads, rice, salt, gold, playing cards or cigarettes could serve as media of exchange in the past. (Boggs united them in an installation for the New York office of the consultancy firm Accenture.) Because many of these means were neither divisible, transportable or perishable, they did not survive the test of time. In that respect, Boggs argues tongue in cheek that his own Sacagawea coin is a good competitor of the original. It is both lighter and larger than the original which makes it easier to distinguish from a quarter.

click to enlarge

Figure 8

David Greg Harth, “I Am

America” dollar bill, July 1998

© David Greg Harth, New York

Figure 9

René Magritte,

Ceci n’est pas une pipe

[This is not a pipe], 1926

David Greg Harth, another American artist with a fascination for money, underscores that the value of money is ultimately founded on trust.(Fig. 8)

7. Keep Boggs in circulation

click to enlarge

Figure 10

J.S.G.Boggs, On Broadway

(Dance Dollar), 1995

Private Collection, Larchmont, NY

Given the fragility of money, it is hardly surprising that Boggs’ proposals arouse such hostile reactions. It confuses people to a greater degree than they are comfortable with. And who can blame them? How easily trust in economic value can be undermined and the consequences have lately been illustrated when investors gained billions of dollars on the NASDAQ and lost them as easily when stock prices collapsed only months later. As mysterious as the rise and fall of the Internet economy is the creation of value that Boggs realizes by printing his own money. Without the help of any official institution–the Central Bank in the last place–he sneaks plastic coins into the economy with a face value of 100.000 dollar. Their real value is even many times higher: a month after their first release, a complete set of six one-dollar coins was sold on Ebay for $87. It goes to show that as painstakingly as the fundamentals of our modern monetary system were established in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, so easily are they tampered with. Or, as Boggs remarks: “When you are dealing with an abstraction, the borderline between something and nothing is very subtle.” (Fig. 10)

Fig. 2

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.

*Works by Boggs © J.S.G. Boggs–courtesy Szilage Gallery