Case Open and/or Unsolved: Étant donnés, the Black Dahlia Murder, and Marcel Duchamp’s Life of Crime

See I have placed

before you an open door that no one can shut.

-Revelation 3:8

The successful criminal brain is always superior…

-Dr. No

I.

In The Trial of Gilles de Rais, Georges Bataille writes, “Crime is a fact of the human species, a fact of that species alone, but it is above all the secret aspect, impenetrable and hidden. Crime hides, and by far the most terrifying things are those that elude us.”(1)

Marcel Duchamp, in both his work and practice, is the elusive artist par excellence. He is the ultimate fugitive of art historical investigation, leaving a trail of tricks, twists, contradictory meanings, and duplicitous identities that lead to epistemological dead-ends. Upon close inspection, Duchamp’s tactics to elude definitive conclusions and vex the viewer reveal themselves as criminal, not unlike those of the con man, fugitive, and even the killer.

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, Given: 1. The Waterfall

2.The Illuminating Gas

(interior),

1946-1966, Gift of the

Cassandra Foundation,

Philadelphia Museum of Art

This paper suggests that Marcel Duchamp consciously toyed with criminal methodologies to elude interpretation and heighten the inconclusive nature of his work. I propose that criminal tactics were one means for Duchamp to enact his rebellion against traditional morality and aesthetics that followed his introduction to the philosopher Max Stirner in 1912. This program emphasizes a continual play on presence/absence, both in the artist’s modes of production and identities. After a brief overview of the apparent criminality of his work, I focus on his final project, Étant donnés (Fig. 1), and suggest that the installation partly derived from a notorious unsolved murder in 1947 known as the “Black Dahlia.”(2) This macabre event reveals remarkable consistencies with Étant donnés, particularly in the identity and character of the victim, Elizabeth Short. Short’s lifestyle embodies uncanny similarities to Duchamp’s decade-long obsessive erotic narrative of the “Bride and her Bachelors,” thus revealing his appropriation of certain details as an enactment of a “copycat” crime in art. Finally, I relate Étant donnés to Duchamp’s earlier works to suggest a reversal of his criminal modus operandi from elusion to hypervisibility. This shift is evident in Étant donnés, which trades conceptual for physical modes of production and complicates the presence/absence of the artist. By furthering the inconclusive nature of Duchamp’s work (through the use of what Jean-Francois Lyotard terms the “hinge”) and being itself most enigmatic, Étant donnés is stamped with the same status as the Black Dahlia murder: open and unsolved.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Nude Descending the Staircase No. 2, 1912

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp,

Three Standard Stoppages, 1913-14

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp,In

Advance of the Broken Arm, 1915/1964, 132 cm, Musée national

d’art moderne, Paris

In 1912, Duchamp first read Max Stirner’s The Ego and His Own, an anarchic text that promoted individualism based on a self-exploration of the ego outside predetermined moral and societal values.(3) The abrupt shift in Duchamp’s aesthetic philosophy that followed his introduction to Stirner, from chronophotographic works such as his famous Nude Descending the Staircase, (Fig. 2) toward works of a more conceptual nature that challenged or defied metaphysics and the values of art and society, such as Three Standard Stoppages (Fig. 3) from 1913-14, is considered a consequence of his introduction to Stirner.(4)Moreover, Amelia Jones has argued the locus of this system was the incorporation of eroticism in both subject and object, which served as the agent to aggressively challenge bourgeois cultural values.(5) The following discussion demonstrates that the nexus between Stirnerite philosophy and eroticism forms an artistic program that produces works that break the “laws” of art, imply criminal play and behavior, and exploit and celebrate the erotic in ways that imply violence to the body.

Duchamp “broke” many artistic rules after his shift toward self-determination. The readymades, such as In Advance of the Broken Arm from 1915 (Fig. 4), are now classic examples of his defiance of the imposed aesthetics of bourgeois society.(6) They not only break the “laws” of art, but also illustrate a form of elusion through their absence of traditional notions of artistic production. As Walter Hopps points out, Duchamp’s career is marked by efforts to suppress the artist’s hand, to remove or disassociate himself from the object through an absence of visual signs that suggest the physical mark of the artist.(7) Duchamp, defying the tradition of physical craft, creates a work that bears only conceptual evidence of its production, having been designated a work of art.(8) The hand and its mark is dangerous to Duchamp. “It’s fun to do things by hand,” he stated, but “I’m suspicious because there’s the danger of the ‘hand’ which comes back…”(9) Direct appropriation of these objects hides the handprint of the artist, as in the lack of fingerprints at a crime scene (is not appropriation, unlike imitation, a kind of stealing?).(10) It is here that Duchamp’s elusion seems to elicit a specifically criminal tone. Moreover, any investigative attempt to trace the sources of these works through the available evidence leads us to hardware stores or factories, not the studio, where any number of these objects were purchased or produced.(11) Ironically, in a recent attempt to do just this, Rhonda Shearer found that the origins of the readymades are often untraceable to any context due to slight alterations by Duchamp, no doubt meant to further complicate attempts to “solve” these works and hinder their investigation.

Nowhere did Duchamp defy conventional aesthetic authority more than in the submission of his famous Fountain (Fig. 5) to the first annual exhibition of the American Society of Artists in 1917.(12) An object so defiant of the “laws” of art, made by simply re-naming and shifting the base of a common urinal, Fountain led a supposedly unjuried exhibition to censorship through its blasphemous suggestions. In addition, Duchamp mocked the committee by signing the work with the alias “R. Mutt” rather than his own name. In this clever tactic, the artist hid his association with the scandalous submission and thus insured his innocence. As a member of the exhibition committee, Duchamp debated the fate of “Mr. Mutt’s” entry much like a criminal who watches their crime scene from a physical distance or under disguise. This, no doubt, amused Duchamp, who continued to emphasize this play on criminal behavior in works such as L.H.O.O.Q., (Fig. 6) defacing the Mona Lisa with a graffiti-style moustache and goatee. Graffiti, itself an illegal form of art, involves the elusive presence/absence of an artistic “criminal” for its production and reception. In other capers, such as his fraudulent checks such as Tzanck Check (Fig. 7) from 1919, Duchamp focused on the act of counterfeiting. And in Wanted (Fig. 8), from 1923, the artist fashioned a literal image of himself as a fugitive with multiple aliases (again emphasizing absence), complete with profile photographs like those of an ex-convict with a prior record.(13)

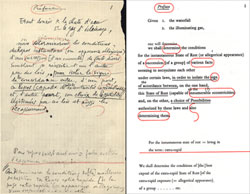

click to enlarge

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp,

Note in the Green Box (1934)

Figure 10

Marcel Duchamp, Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [a.k.a.

The Large Glass], 1915-23

All of these acts might be described as “petty crimes” when compared to his last work, the installation in the Philadelphia Museum of Art entitled, Étant donnés: 1 la chute d’eau, 2 le gaz d’éclairage – translated as Given: 1. The Waterfall 2. The Illuminating Gas. The title of this piece, taken from the opening lines of an introductory note to Duchamp’s Green Box (Fig. 9), signals its association with his earlier work The Large Glass, (Fig. 10) and suggests its representation as a three-dimensional version of the narrative of the Bride and her Bachelors.

Étant donnés has baffled scholars since its discovery after the artist’s death in 1968, when following Duchamp’s instructions, it was reinstalled in the Philadelphia Museum of Art by Anne d’Harnoncourt and Paul Matisse in 1969. With the exception of a select group of individuals that included the artist’s wife Alexina Matisse and her son Paul, the work was created by Duchamp in secrecy in New York City, first in his studio at 210 West 14th Street and later moved to another small room on 80 East Eleventh Street around 1965.(14) The majority of scholarship that discusses the body in Étant donnés focuses on readings that emphasize violation, murder, rape, or other acts that associate criminal violence, eroticism, and the body.(15) It has been described as a “mutilated woman” and a “seemingly dead female body,” suggesting that some form of criminal activity either already transpired or is about to occur.(16) The erotic nature of these violent interpretations is based largely on the positioning of the body and Duchamp’s choice to explicitly display the female groin region, which is overtly shown to the viewer who peers through the small eyeholes in the door that houses the installation. The body, in its placement before us with legs spread apart, shocks the viewer because of what numerous scholars refer to as its “hypervisibility.”(17)

II.

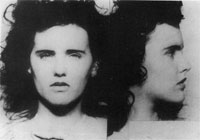

click to enlarge

Figure 11

Photograph of Elizabeth Short

for civilian employee ID

Figure 12

LAPD Detectives Harry Hansen

and Finis Brown with Elizabeth Short’s

body, January 15th, 1947,

Museum of Death

On the morning of January 15th, 1947, the mutilated body of Elizabeth Short, an aspiring starlet known as the “Black Dahlia” for her stunning beauty and jet black hair, was found purposefully placed on the edge of an open lot on Norton Avenue in Los Angeles, California (Fig. 11).(18) For the next few months at first, then years as the case went on, her name littered the headlines of West and East coast newspapers that described in detail both her flamboyant lifestyle and macabre death. To this day, the Black Dahlia murder case remains California’s most notorious unsolved crime. The following discussion suggests that the media presentation and crime photographs of the Black Dahlia murder, contemporaneous to Duchamp’s conception of Étant donnés, may have affected its design and progress.

The parallels between the Black Dahlia and Étant donnés are numerous. By far the most striking similarity involves the two bodies. In a photograph of Elizabeth Short’s body at the crime scene, she lies in thick, tall grass not unlike the twigs that surround the body in Étant donnés; her legs spread wide displaying her sex (Fig. 12). And, in the most grisly detail of this heinous crime, her body is no longer whole; it has been severed at the waist. In a surrealist fantasy become reality, the Black Dahlia represents a real-life example of what was envisioned in the contemporaneous paintings, photographs, and installations of artists such as Hans Bellmer, Rene Magritte, Man Ray, and even Marcel Duchamp. Often times, for example, these surrealist artists would manipulate mannequins in their works for both their uncanny mixture of life-like and lifeless qualities, as well as their constructive and deconstructive potential through detachable anatomical parts. As the photograph illustrates, Short’s mid-section was not only severed in a manner similar to these detachable dummies, but, coincidentally, her body was actually mistaken for a mannequin by a passer-by who, observing the severed torso and skin that was “white as a lily,” believed it came from a department store.(19)

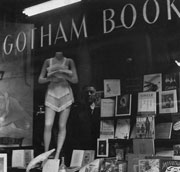

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Marcel Duchamp, Lazy

Hardware, window display for André

Bretons Arcane 17, 19.-26.

April 1945, Gotham Bookmart, E. 57th

St. New York,

Photography Maya Deren,

Philadelphia Museum of Art,

Marcel Duchamp

Archive.

Duchamp found both inspiration and direct use for mannequins throughout his career. He explained to Man Ray in the early 1920’s that the origin of the Bride theme came from the “brides in booths” at French Country Fairs, where dummies dressed as a bride and groom were used as targets for people to throw balls in an attempt to decapitate them.(20) Closer in time to the Black Dahlia and Étant Donnés is his display window at the Gotham Book Mart in New York City from 1945 to promote Andre Breton’s surrealist publication Arcane 17 (Fig. 13); where Duchamp installed a headless female mannequin that immediately caused a scandal with the League of Women.(21)

The two most forceful formal similarities between the Black Dahlia and the body in Étant donnés are located in the groin region of each figure. First, both Elizabeth Short’s body and the body in Étant donnés have no pubic hair. The lack of hair in Étant donnés has been discussed in relation to Duchamp’s interest in gender indeterminacy, as well as a tale of the Baroness Else von Freytag-Loringhoven, who had her pubic area shaved by a barber in a film that both Duchamp and Man Ray collaborated on.(22) Furthermore, in the memoirs of Lydie Sarazin-Levassor, Duchamp’s wife for eight months in 1927-28, she claims that Duchamp requested she remove her body hair, owing to his “almost morbid horror of hair.”(23) In light of these past incidents, the absence of pubic hair from Short’s body, in itself, could have proved alluring to Duchamp.

But Short’s body also offers an explanation for the strange, incorrect anatomy that suggests a female vagina in Étant donnés. Amelia Jones has negated the conclusions of earlier scholars who discussed the genitalia of Duchamp’s figure in terms of the anatomy of the female sex, proving that there is in fact no labia majora or labia minora. What exists instead is what she calls an “aggressively visible and grotesque gash that goes nowhere.”(24) In the photograph of the Black Dahlia murder one can see a literal gash that was incised above the vagina into the lower abdomen of the body of Elizabeth Short (Fig. 14). It is now known through the disclosure of the autopsy reports that Elizabeth Short’s pubic area was underdeveloped. Detectives and crime experts suspect that the gash was a means for the sexually ravenous killer to insert himself into Short, whose genitals were underdeveloped and therefore unable to engage in vaginal intercourse.(25)

Thus, the Dahlia could not offer her bachelors a natural way to fulfil their lustful desires, much like the failure of the love operation in Duchamp’s narrative of the Large Glass where the “bachelors grind their chocolate.”(26) The “gash” in Étant donnés first appeared in a vellum study for the figure in 1948-49 (Fig. 15), and the transition from a drawing dated controversially either 1945 or 1947 (Fig. 16), which features a female body without head and arms (severed?) with natural pubic hair, to the hairless body with a single “gash” in the vellum study has never been explained.(27) If Duchamp was exposed to the Dahlia murder, either in 1947 or 1949 (this will be discussed in more detail shortly), then perhaps this event was the impetus for these design alterations. Chronologically, the murder (and his exposure to it) fits neatly between the otherwise inexplicable transition from the drawing to the vellum study.

Figure 14

Elizabeth Short’s body, January

15th, 1947, Museum of Death

Figure 15

Marcel Duchamp, The Illuminating Gas and the Waterfall, 1948-49,

Moderna Museet, Stockholm

Figure 16

Marcel Duchamp, Given: Maria, The Waterfall, and the Illuminating Gas,

1947

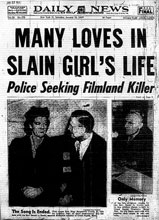

click to enlarge

Figure 17

New York

Daily News Headline, January 18th, 1947

Figure 18

Marcel Duchamp, Fresh Widow, 1920

The story of Elizabeth Short presented in the newspapers during the investigation also parallels aspects of Duchamp’s own erotic narrative. Short’s failure to fulfil the “love operation,” while not directly stated through a medical explanation, was implied through accounts in the papers that spoke of her teasing nature and relationships that ended “before the love was consummated,” echoing Duchamp’s non-consummation and frustration in the theme of the Large Glass.(28) Moreover, the newspapers on both coasts played-up a controversial aspect of her past, in which she claimed to have married an air force pilot who in fact died before the ceremony could take place.(29) Thus, Elizabeth Short appeared to be paradoxically married and unmarried. The newspapers furthered the confusion when they obtained information from her address book, which contained “an album of pictures ranging in rank from sergeant to lieutenant general.”(30)

Several newspapers ran stories that published a long list of “Bachelors,” as in the New York Daily News headline from January 18th 1947 that reads, “Many Loves in Slain Girl’s Life”(Fig. 17).(31) As Jean-Francois Lyotard and others point out, Duchamp complicates attempts to locate fixed meanings in his works through what has been called a “hinge” effect.(32) The hinge, represented in language by the juxtaposition of “and/or,” as in the double alias of Marcel Duchamp and/or Rrose Sélavy, is both single and multiple, definitive and simultaneously inconclusive. To extend the “hinge” interpretation, the Dahlia was a Duchampian fantasy come to life―single and/or married, Elizabeth Short and/or the Black Dahlia, whole and/or severed, life and/or art. Like the Bride in Duchamp’s tale, who has “no singular, definitive groom,” the Dahlia represents eroticism and violence staged in these photographs as a literal “Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even(ly) cut” as a symbol of the artist’s concept of infra-mince, a physical cut that in this context plays itself out in a long list of Duchampian metaphors.(33)She is a “Fresh Widow,” like the French women Duchamp referred to after the First World War in his 1920 work of the same name (Fig. 18); a work whose title also, coincidentally (?), references the guillotine―“the Widow, in popular French jargon.”(34) Lastly, in several of the crime scene photographs and those of the newspapers, the detectives, policemen, and reporters seem to echo Duchamp’s description of his Occulist Witnesses and bachelors, who “stand, sadly, in ‘uniforms and liveries’” and observe the spectacle before them.(35) (Figs. 19 & 20)

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Marcel Duchamp,

Occulist Witnesses,

from Green Box

(1934), 1920

Figure 20

Marcel Duchamp,

Cemetery of Uniforms

and Liveries, No. 2,

1914

III.

In mid-January 1947 Duchamp returned from a stay in Europe, arriving in New York at the moment the Dahlia case began to unfold. The particulars of the murder and its surrounding controversies were appearing daily in newspapers. The New York Daily News ran headlines and follow-up stories about the Dahlia murder for several weeks.(36) More importantly, at the time of the killing Los Angeles was the home of the artist’s close friend Man Ray. The relationship between these two artists is well documented, and Man Ray’s influence on Duchamp’s conception of Étant donnés has already been suggested.(37) In addition to being engulfed in a sea of newspaper headlines and Hollywood gossip about the killing, Man Ray, like Elizabeth Short, frequented the popular bars and clubs in Hollywood and knew many people in the jet set of the movie community.(38) With his lifelong fascination with sado-masochism, Man Ray would certainly have taken an interest in the particulars of this crime.(39) As a photographer of such repute, Man Ray might have been able to obtain one of the many hundreds of crime scene photographs taken by reporters that circulated through the Hollywood community.(40) These photographs were reproduced and passed from hand-to-hand, and were not censored like the newspaper photographs that displayed the body in situcovered with a sheet, nor were they the “cleaned-up” autopsy photographs that appeared in detective and crime magazines.

click to enlarge

Figure 21

Marcel Duchamp and

Man Ray in Los Angeles,

California, 1949

On his way back from Paris in 1947, the year of the murder, Man Ray spent a week in New York City.(41) This could have served as an occasion for him to share this information with Duchamp, either simply for its grisly, surrealist nature or for its many similarities with his own and Duchamp’s beliefs and work. If this was not the case, Duchamp may have heard or seen something about the Black Dahlia during his visit to the Arensberg’s home in Los Angeles two years later in April 1949 after his participation in a Round Table discussion in San Francisco.(42) The Black Dahlia case was again making news with new suspects, and moreover Duchamp spent each afternoon secretly meeting with Man Ray by taking “afternoon walks.”(43) In this photograph (Fig. 21), the two artists, in a witty false “alibi,” sit on a stage set in Hollywood designed as a Parisian street corner. Why wouldn’t someone with a penchant for criminal tactics, who characterized his interest in eroticism as “Enormous. Visible or not underlying in every case…” be fascinated by this crime?(44) In an interview with Walter Hopps during his stay in Los Angeles, Duchamp declared he was going through his “sex maniac” phase, a phrase which coincidentally appeared in newspaper articles such as the first Los Angeles Times piece on the Dahlia Murder, which opened with the lines, “Butchered by a sex maniac…”(45) It is not surprising then, that upon his return to New York, Duchamp sent the clay model for the body in Étant donnés out for casting in plaster and, as Calvin Tomkins describes in his biography on Duchamp, “by summer he was working on it with great intensity―up to eight hours a day…”(46)

click to enlarge

Figure 22

Marcel Duchamp,

Female Fig Leaf,

1950

Figure 23

Marcel Duchamp,

Wedge of Chastity,

1954

These events and shared interests between Duchamp and Man Ray in the context of the Black Dahlia suggest new meanings for two of Duchamp’s later erotic objects, Female Fig Leaf and Wedge of Chastity (Figs. 22 & 23). If Man Ray was partly responsible for introducing Duchamp to the Black Dahlia in 1947 or 1949, this may explain the nature of Duchamp’s gift, Female Fig Leaf, to the photographer. On his return to Paris with his new wife Juliet in 1951, Man Ray was surprised by Duchamp, who was waiting onboard in the couple’s cabin in port in New York City.(47) Duchamp presented Man Ray with an object described as a “wax impression of what looked like a woman’s vulva.”(48) Could this be a hint, or subliminal reference to the body in Étant donnés (or the Dahlia)?(49)

Did this object imply something more than a simple shared interest in eroticism in the form of a farewell gift? With Duchamp’s love of puns and double meanings, one wonders if a linkage to Étant donnés and/or the Black Dahlia continued with the verbal/visual play in another erotic object,Wedge of Chastity. A wedding gift to his wife Alexina (Teeny) Sattler, Duchamp inscribed the object with the phrase, “Pour Teeny 16. Jan. 1954.” The spoken phrase, “Pour Teeny,” in English carries an additional meaning; “poor teeny,” as in the poor starlet who could not fulfil the “love operation” because of her “Wedge of Chastity.” Is it surprising that this “wedge” seems to fit snugly into a kind of “gash?” Or that January 16thwas also the day after the murder of Elizabeth Short, the first day the headlines appeared in New York City papers?

IV.

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors Even [a.k.a.

The Green Box], 1934

Similar to Étant donnés, the Black Dahlia case perplexed investigators, and “facts” were constantly being undermined by the introduction of contradictory evidence. These inconclusive theories were played out, among other places, in newspaper headlines that emphasized the “gender indeterminacy” of the suspect. Authorities, first suspecting a man, reversed their hypothesis. The press ran headlines such as “Woman Now Sought In Black Dahlia Killing.”(50) Ironically, the case’s most plausible suspect is now a female impersonator―how Duchampian.(51)Quotes from detectives appeared in the papers as well, such as a statement from Detective Harry Hansen who regrettably admitted, “No lead had any conclusion, once we’d find something, it seemed to disappear in front of our eyes. Following any of those leads was like going down one-way streets with dead-ends.”(52) When a suitcase of the victim’s belongings turned up, it was filled with all kinds of objects―beauty supplies, photographs of men she had known, letters, etc. In a stunningly similar manner to Duchamp’s Box in a Valise, or better yet Green box, the suitcase’s contents guided detectives in their investigation much as the Green Box serves as a “guide” to the Large Glass. (Fig. 24)

In this sense, the Black Dahlia/ Étant donnés comparison can be viewed as the complicated performance of what criminologists term a “copycat” crime, played out within the sphere of art. Elizabeth Short’s life represents Duchamp’s pre-existing tale within the context of a specific time and place. Yet Étant donnés, continuing Duchamp’s penchant for criminal play, becomes a kind of “copycat” crime by re-using a specifically criminal mode of appropriation, and possibly specific details from this crime, as a “readymade” for certain features of his installation. The cyclical indeterminacy of “who copied who” once more suggests the “hinge,” represented this time by the Dahlia murder, which negotiates between the narrative of the Large Glass and Étant donnés (it is amusing as well that the linguistic symbol for Lyotard’s hinge has at its center a slash that “severs” the “and/or” indeterminate). Thus, Duchamp’s narrative and/or the life of Elizabeth Short―the Dahlia murder and/or Étant donnés.

Unlike the Large Glass, however, which presented cryptic visual versions of erotic narratives, Duchamp in Étant donnés, shocked his art audience by performing a spectral flip of his criminal modus operandi. What was, up to this point in his career hidden, was suddenly blatantly revealed.(53) As detective Jess Haskins said of the Dahlia murder, “It was not unusual―the ‘display idea’ as part of a sex crime…Hiding it had been the least of the perpetrator’s concerns.”(54) Duchamp, it is well known, claimed that eroticism was “a way to bring out in the daylight the things that are constantly hidden….because of social rules.”(55)Thus, the earlier use of criminal and erotic subjects and actions emphasized the elusive absence of the living artist and cryptic narratives. Conversely, Étant donnés presents a hypervisible, blatant operation through another kind of artistic absence, first by, as he said, “going underground” during the secret and elusive production of Étant donnés, then through his literal absence in death.(56) In this role reversal, Duchamp exposes the crime and hides himself, like a serial killer, whose “psychosexual nexus is terra incognita.”(57)

As in many famous unsolved murders, Elizabeth Short’s body was not simply dumped in a lot; it was deliberately arranged.(58) Her two halves were placed to repeat the natural position of the body several hours after the actual crime occurred. This gave the crime scene what detectives characterized as a “sacred setting,” implying that messages or meanings could be yielded by its purposeful display.(59) Duchamp also stresses his intentional positioning and display of the body in Étant donnés, controlling among other things our line of vision. As his title implies, we are presented with certain “evidence” from which to attempt to solve this artwork and/or crime.(60) The title, presented in the format of a mathematical equation, ironically suggests that this piece can be “solved” through a logistical program. “Given” it implies, “the waterfall, the illuminated gas, and whatever else you can see.” Here the spectral flip appears to hide the conceptual and offer an overtly constructed physical art environment.(61) Moreover, Duchamp’s strategic placement of Étant donnés at the far rear of the Arensberg room in the Philadelphia Museum of Art creates two further paradoxes. One, it is literally “hidden” in a dark retreat at the back of the “display,” yet shockingly reveals itself within the darkness when the viewer looks through the peepholes. Second, the entire Arensberg room creates an exhibition narrative based on a body of work, that ends with a literal body. The post-Stirnerite works in the brightly lit outside gallery hide the physical mark and presence of their creator and engage us through the conceptual and extra-dimensional. The dark hidden room of Étant donnés offers us the physical, both as literal body and as an attempt in understanding based on the empirical act of seeing.

click to enlarge

Figure 25

Marcel Duchamp, epitaph

inscribed on Duchamp’s

grave stone, 1968

In death, Duchamp left a corpus and a corpse. His permanent absence was certainly his ultimate act of elusion. As in the Black Dahlia murder, the death of the “suspect” stamps Étant donnés permanently “open and unsolved.” We can never “break the case” of Marcel Duchamp (although we can break his works of art). In denying us solutions, Duchamp also denies us from closing the book on his work; its inconclusive nature leaves it inevitably open and alive. Thus, by defying solution, perhaps he and his work even defy death. “Besides,” his self-written epitaph reads, “it’s only the others that die.”(62) (Fig. 25) This, it seems, is Duchamp’s only truth.

Notes

1. G. Bataille,The Trial of Gilles de Rais, trans. Richard Robinson (Los Angeles,1991) 13. I was inspired to begin this essay with these words by Stuart Swezey, who included Bataille’s statement in his preface to John Gilmore’s book, Severed:The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder, Los Angeles, 1994.

1. G. Bataille,The Trial of Gilles de Rais, trans. Richard Robinson (Los Angeles,1991) 13. I was inspired to begin this essay with these words by Stuart Swezey, who included Bataille’s statement in his preface to John Gilmore’s book, Severed:The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder, Los Angeles, 1994.

2. For a full account of this tragedy, see J. Gilmore, Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder (Los Angeles, 1994).

2. For a full account of this tragedy, see J. Gilmore, Severed: The True Story of the Black Dahlia Murder (Los Angeles, 1994).

3. F. M. Naumann,“Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites”, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. R. Kuenzli and F. M. Naumann (Cambridge,Massachusetts, 1989) 29.

3. F. M. Naumann,“Marcel Duchamp: A Reconciliation of Opposites”, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. R. Kuenzli and F. M. Naumann (Cambridge,Massachusetts, 1989) 29.

4. M. Stirner, The Ego and Its Own (New York, 1907) 361. Duchamp himself stated that his reading of Stirner “marked his complete liberation.” A. Antliff, “Anarchy, Politics, and Dada”, In Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York (Whitney Museum, 1996) 212.

4. M. Stirner, The Ego and Its Own (New York, 1907) 361. Duchamp himself stated that his reading of Stirner “marked his complete liberation.” A. Antliff, “Anarchy, Politics, and Dada”, In Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York (Whitney Museum, 1996) 212.

5. A. Jones, “Eros, That’s Life or the Baroness’ Penis”, In Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York (Whitney Museum, 1996) 239.

5. A. Jones, “Eros, That’s Life or the Baroness’ Penis”, In Making Mischief: Dada Invades New York (Whitney Museum, 1996) 239.

6. Antliff makes the connection between Duchamp’s adoption of Stirner’s philosophy and a revolt against what he calls “the rules ‘art’ imposed on the individual.” Antliff, op. cit., p. 213.

6. Antliff makes the connection between Duchamp’s adoption of Stirner’s philosophy and a revolt against what he calls “the rules ‘art’ imposed on the individual.” Antliff, op. cit., p. 213.

7. W. Hopps and A. d’Harnoncourt, Etant Donnés: 1 la chute d’eau 2 le gaz d’éclairage: Reflections on a New Work by Marcel Duchamp, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin (second reprint) Volume LXIV, Numbers 299 and 300, (April-September 1969, Philadelphia, 1987) 37.

7. W. Hopps and A. d’Harnoncourt, Etant Donnés: 1 la chute d’eau 2 le gaz d’éclairage: Reflections on a New Work by Marcel Duchamp, Philadelphia Museum of Art Bulletin (second reprint) Volume LXIV, Numbers 299 and 300, (April-September 1969, Philadelphia, 1987) 37.

8. In this sense, I disagree with Antliff’s characterization of the American readymades.He states, “Here Duchamp undermined the metaphysical aesthetics and socially imposed conventions that defined ‘art,’ replacing painting and sculpture with mass-produced objects devoid of aesthetic deliberation and any trace of the creative process.” In my opinion, the readymades are neither devoid of aesthetic deliberation nor lacking any trace of the creative process. What the readymades lack are physical traces (visually recognizable) of creation. Instead, the evidence of a creative process is solely conceptual. Antliff, op. cit., p. 213.

8. In this sense, I disagree with Antliff’s characterization of the American readymades.He states, “Here Duchamp undermined the metaphysical aesthetics and socially imposed conventions that defined ‘art,’ replacing painting and sculpture with mass-produced objects devoid of aesthetic deliberation and any trace of the creative process.” In my opinion, the readymades are neither devoid of aesthetic deliberation nor lacking any trace of the creative process. What the readymades lack are physical traces (visually recognizable) of creation. Instead, the evidence of a creative process is solely conceptual. Antliff, op. cit., p. 213.

9. P. Cabanne,Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris, 1967) 165, trans. D. Judovitz, “Rendezvous with Marcel Duchamp: Given”, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. R.E. Kuenzli and F. M. Naumann (Cambridge, Mass, 1989) 197.

9. P. Cabanne,Entretiens avec Marcel Duchamp (Paris, 1967) 165, trans. D. Judovitz, “Rendezvous with Marcel Duchamp: Given”, Marcel Duchamp: Artist of the Century, ed. R.E. Kuenzli and F. M. Naumann (Cambridge, Mass, 1989) 197.

10. As Steven Levine pointed out during the discussion of this paper at the Symposium for the History of Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, imitation could certainly be considered “criminal” as well. As early as Antiquity, the deceitful nature of artistic imitation led Plato to exclude it from his ideal Republic.

10. As Steven Levine pointed out during the discussion of this paper at the Symposium for the History of Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, imitation could certainly be considered “criminal” as well. As early as Antiquity, the deceitful nature of artistic imitation led Plato to exclude it from his ideal Republic.

11. As Rhonda Shearer points out, it is possible that these objects were not appropriated exactly as they were “found” by Duchamp. Manufacturer catalogs contemporary to the readymades do not contain illustrations that directly match some of Duchamp’s objects. Thus, she suggests the artist may have altered them slightly to further confuse their “origin.” In L. Cambi, “Did Duchamp Deceive Us?”, Art News, v 98 (February 1999) 98-102. Moreover, we know from photographs and remarks by Man Ray that Duchamp’s studio was, for the most part, bare. This also suggests that the artist wished to confuse any attempts to “trace” the source material or influences of his work.

11. As Rhonda Shearer points out, it is possible that these objects were not appropriated exactly as they were “found” by Duchamp. Manufacturer catalogs contemporary to the readymades do not contain illustrations that directly match some of Duchamp’s objects. Thus, she suggests the artist may have altered them slightly to further confuse their “origin.” In L. Cambi, “Did Duchamp Deceive Us?”, Art News, v 98 (February 1999) 98-102. Moreover, we know from photographs and remarks by Man Ray that Duchamp’s studio was, for the most part, bare. This also suggests that the artist wished to confuse any attempts to “trace” the source material or influences of his work.

12. It could be argued that Duchamp’s “outlaw” status began even earlier, when he submitted his Nude Descending the Staircase to the 1913 Armory exhibition.

12. It could be argued that Duchamp’s “outlaw” status began even earlier, when he submitted his Nude Descending the Staircase to the 1913 Armory exhibition.

13. Judovitz first suggested that Duchamp possessed criminal qualities in her discussions of Tzank Check and Wanted in Chapter 4 of Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. Her interpretation and discussion of criminality, however, rests solely on the idea of counterfeiting and fake transactions. D. Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (Berkeley, 1995) 167-78. This paper suggests that these are but two of many examples within Duchamp’s artistic career in which he looked to criminality as a means of reconciling his philosophical and aesthetic/non-aesthetic programs. Moreover, Duchamp’s Wanted is included here to emphasize, through his multiple aliases and criminal image, the connection between criminality and elusion (absence).

13. Judovitz first suggested that Duchamp possessed criminal qualities in her discussions of Tzank Check and Wanted in Chapter 4 of Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit. Her interpretation and discussion of criminality, however, rests solely on the idea of counterfeiting and fake transactions. D. Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: Art in Transit (Berkeley, 1995) 167-78. This paper suggests that these are but two of many examples within Duchamp’s artistic career in which he looked to criminality as a means of reconciling his philosophical and aesthetic/non-aesthetic programs. Moreover, Duchamp’s Wanted is included here to emphasize, through his multiple aliases and criminal image, the connection between criminality and elusion (absence).

14. J. A. Ramirez, Duchamp: Love and Death, Even (London, 1998) 199.

14. J. A. Ramirez, Duchamp: Love and Death, Even (London, 1998) 199.

15. The most complete investigation of the nude body in Etant donnés, its influences, and location within a history of nudes in the landscape is Antonio Juan Ramirez’s discussion in his book Duchamp: Love and Death, Even. In an attempt to separate fact from hearsay, Ramirez asks an important question: “What kind of things might Duchamp have seen or read; with which intellectual wave and artistic movement was he associated at any given moment?” ibid., p. 12. Ramirez’s discussion focuses, for the most part, on art historical sources beginning as early as the end of the 15th century and ending with the surrealist work of Hans Bellmer and others. While he does briefly mention that popular photographs of pornographic subjects were more important than art historical images of the nude, his discussion of this material is brief, and indirect. Rather than answering his own question in relation to this material, Ramirez offers visually similar images but fails to contextualize them and discuss the direct avenues through which Duchamp may have seen or obtained them. Therefore, re-asking Ramirez’s question, I offer the Black Dahlia as a more convincing non-art historical influence.

15. The most complete investigation of the nude body in Etant donnés, its influences, and location within a history of nudes in the landscape is Antonio Juan Ramirez’s discussion in his book Duchamp: Love and Death, Even. In an attempt to separate fact from hearsay, Ramirez asks an important question: “What kind of things might Duchamp have seen or read; with which intellectual wave and artistic movement was he associated at any given moment?” ibid., p. 12. Ramirez’s discussion focuses, for the most part, on art historical sources beginning as early as the end of the 15th century and ending with the surrealist work of Hans Bellmer and others. While he does briefly mention that popular photographs of pornographic subjects were more important than art historical images of the nude, his discussion of this material is brief, and indirect. Rather than answering his own question in relation to this material, Ramirez offers visually similar images but fails to contextualize them and discuss the direct avenues through which Duchamp may have seen or obtained them. Therefore, re-asking Ramirez’s question, I offer the Black Dahlia as a more convincing non-art historical influence.

16. A “seemingly dead female body” in A. Jones. Postmodernism and the Engendering of Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, 1994) 192 and a “mutilated woman” in Ramirez, op.cit., p. 234.

16. A “seemingly dead female body” in A. Jones. Postmodernism and the Engendering of Marcel Duchamp (Cambridge, 1994) 192 and a “mutilated woman” in Ramirez, op.cit., p. 234.

17. This is discussed, among others, by J. A. Ramirez, D. Judovitz, and A. Jones.

17. This is discussed, among others, by J. A. Ramirez, D. Judovitz, and A. Jones.

18. As Gilmore explains, soldiers began to call Elizabeth Short by this name as a re-worked version of a recent film entitled “The Blue Dahlia.” The “Black Dahlia” quickly became a nickname that soldiers would use in their queries as to whether she had been spotted somewhere on the streets each day. Gilmore, op. cit., p.56.

18. As Gilmore explains, soldiers began to call Elizabeth Short by this name as a re-worked version of a recent film entitled “The Blue Dahlia.” The “Black Dahlia” quickly became a nickname that soldiers would use in their queries as to whether she had been spotted somewhere on the streets each day. Gilmore, op. cit., p.56.

19. Elizabeth Short’s body had been drained of blood prior to being dumped in the lot, explainingwhy it appeared “white as a lily.” ibid., p. 5.

19. Elizabeth Short’s body had been drained of blood prior to being dumped in the lot, explainingwhy it appeared “white as a lily.” ibid., p. 5.

20. A. Schwartz,Man Ray: The Rigour of the Imagination (New York, 1977) 188.

20. A. Schwartz,Man Ray: The Rigour of the Imagination (New York, 1977) 188.

21. Hoppsand d’Harnoncourt, op. cit., p. 32.

21. Hoppsand d’Harnoncourt, op. cit., p. 32.

22. D. Hopkins,“Men Before the Mirror: Duchamp, Man Ray and Masculinity”, Art History,v 21 (September 1998)s 317.

22. D. Hopkins,“Men Before the Mirror: Duchamp, Man Ray and Masculinity”, Art History,v 21 (September 1998)s 317.

23. Le Recit de Lydie, Rrosopopees 19-20 March 1989: 489.

23. Le Recit de Lydie, Rrosopopees 19-20 March 1989: 489.

24. Jones, Postmodernism and.., op. cit., p. 201.

24. Jones, Postmodernism and.., op. cit., p. 201.

26. L.D. Steefel, Jr., The Position of Duchamp’s Glass in the Development of His Art (New York, 1977) 167.

26. L.D. Steefel, Jr., The Position of Duchamp’s Glass in the Development of His Art (New York, 1977) 167.

27. This suggests a more convincing date for the first drawing as 1947 rather than 1945. If Duchamp had seen the photographs of the Black Dahlia, then perhaps they might explain an origin for the pose of the figure, usually referred to as Marie Martins. In addition, the last number of the date inscribed on this drawing, in my opinion, looks much more like a “7” than a “5.” Calvin Tomkins also identifies the date of this drawing as 1947. C. Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (New York, 1996) 357.

27. This suggests a more convincing date for the first drawing as 1947 rather than 1945. If Duchamp had seen the photographs of the Black Dahlia, then perhaps they might explain an origin for the pose of the figure, usually referred to as Marie Martins. In addition, the last number of the date inscribed on this drawing, in my opinion, looks much more like a “7” than a “5.” Calvin Tomkins also identifies the date of this drawing as 1947. C. Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (New York, 1996) 357.

28. Detective Brown, speaking about the letters found in her suitcase. Gilmore, op. cit., p.

28. Detective Brown, speaking about the letters found in her suitcase. Gilmore, op. cit., p.

29. “Mother of Hero Doubts Marriage to Short Girl”, Los Angeles Times 19 Jan. 1947: 3.

29. “Mother of Hero Doubts Marriage to Short Girl”, Los Angeles Times 19 Jan. 1947: 3.

30.Daily News, New York, 18 Jan. 1947: 1,3.

30.Daily News, New York, 18 Jan. 1947: 1,3.

32. See J.F. Lyotard, Duchamp’s TRANS/formers, Venice, CA, 1990, pp. 58-61, and D. Judovitz. Unpacking Duchamp, op. cit., p. 215.

32. See J.F. Lyotard, Duchamp’s TRANS/formers, Venice, CA, 1990, pp. 58-61, and D. Judovitz. Unpacking Duchamp, op. cit., p. 215.

33. For a detailed discussion of infra-mince, see M. Nesbit “Last Words: (Rilke, Wittgenstein) (Duchamp)”, Art History 21 (December 1998): 547. There are other striking similarities between the images of the Black Dahlia crime scene and Duchamp’s studies for Etant donnés, especially a drawing from 1959 in which the Large Glass is juxtaposed with a landscape that includes telephone poles. These appear in the same area as some of the telephone poles in several crime scene photographs. Moreover, the Occulist Witnesses in Duchamp’s drawing occupy the same position as the policemen and detectives in the crime scene photographs.

33. For a detailed discussion of infra-mince, see M. Nesbit “Last Words: (Rilke, Wittgenstein) (Duchamp)”, Art History 21 (December 1998): 547. There are other striking similarities between the images of the Black Dahlia crime scene and Duchamp’s studies for Etant donnés, especially a drawing from 1959 in which the Large Glass is juxtaposed with a landscape that includes telephone poles. These appear in the same area as some of the telephone poles in several crime scene photographs. Moreover, the Occulist Witnesses in Duchamp’s drawing occupy the same position as the policemen and detectives in the crime scene photographs.

34. O. Paz, Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1978, p. 122.

34. O. Paz, Marcel Duchamp, New York, 1978, p. 122.

35. A. Jones, “Eros..”, op. cit., p. 240.

35. A. Jones, “Eros..”, op. cit., p. 240.

36. From January 18th, 1947 through early February the New York Daily News ran three front-page stories, and fourteen other articles that appeared somewhere on the first five pages of the newspaper (most on them on page three).

36. From January 18th, 1947 through early February the New York Daily News ran three front-page stories, and fourteen other articles that appeared somewhere on the first five pages of the newspaper (most on them on page three).

37. See for example Ramirez, who claims that these “aspects (photographs), along with the adventures shared by the two friends suggests (as we shall see) Man Ray’s considerable influence on Duchamp.” Ramirez, op. cit., p. 221.

37. See for example Ramirez, who claims that these “aspects (photographs), along with the adventures shared by the two friends suggests (as we shall see) Man Ray’s considerable influence on Duchamp.” Ramirez, op. cit., p. 221.

38. Elizabeth Short is known to have frequented the following locales: Four Star Grill, Florentine Gardens, The Rhapsody, the Dugout, the Loyal Café, and the Streets of Paris. Moreover, in an email correspondence, John Gilmore informed me that there was a strong possibility that Man Ray may have known the Black Dahlia, or at least met her.

38. Elizabeth Short is known to have frequented the following locales: Four Star Grill, Florentine Gardens, The Rhapsody, the Dugout, the Loyal Café, and the Streets of Paris. Moreover, in an email correspondence, John Gilmore informed me that there was a strong possibility that Man Ray may have known the Black Dahlia, or at least met her.

39. For a summary see A. Schwartz, Man Ray, p.187-190. The articles in the

39. For a summary see A. Schwartz, Man Ray, p.187-190. The articles in the

Los Angeles Times and the Examiner, for example, discuss the sado-masochistic aspects of the crime.

40. In John Gilmore’s book, Detective Brown is quoted in the autopsy room as saying, “There are already a thousand photographs… You can see most of what’s been done…..” Gilmore, op. cit., p. 126.

40. In John Gilmore’s book, Detective Brown is quoted in the autopsy room as saying, “There are already a thousand photographs… You can see most of what’s been done…..” Gilmore, op. cit., p. 126.

41. M. Ray, Self Portrait: Man Ray, Boston, 1988, p. 291.

41. M. Ray, Self Portrait: Man Ray, Boston, 1988, p. 291.

42. For a summary of Duchamp’s participation in this event, as well as a chronology of his California experiences, see B. Clearwater, West Coast Duchamp (Miami, 1991).

42. For a summary of Duchamp’s participation in this event, as well as a chronology of his California experiences, see B. Clearwater, West Coast Duchamp (Miami, 1991).

45. “Girl Victim of Sex Fiend Found Slain”, Los Angeles Times, Thursday, 16 Jan. 1947: 2. The interview with Hopps is quoted from Tomkins, op. cit., p.423.

45. “Girl Victim of Sex Fiend Found Slain”, Los Angeles Times, Thursday, 16 Jan. 1947: 2. The interview with Hopps is quoted from Tomkins, op. cit., p.423.

46. Tomkins, op. cit., p. 366.

46. Tomkins, op. cit., p. 366.

48. Tomkins, op. cit., p. 370.

48. Tomkins, op. cit., p. 370.

49. To my knowledge, no one has ever made a cast of the female groin region of the body in Etant donnés. It could be possible that Female Fig Leaf is directly linked to Etant donnés in this way.

49. To my knowledge, no one has ever made a cast of the female groin region of the body in Etant donnés. It could be possible that Female Fig Leaf is directly linked to Etant donnés in this way.  50. “Woman Now Sought in Black Dahlia Killing”, New York Daily News 21 Jan. 1949:5.

50. “Woman Now Sought in Black Dahlia Killing”, New York Daily News 21 Jan. 1949:5.

53. Some scholars were disappointed because this seemed to point to a return to representation that negated Duchamp’s “progress” toward conceptual art.

53. Some scholars were disappointed because this seemed to point to a return to representation that negated Duchamp’s “progress” toward conceptual art.

55. N. Baldwin, Man Ray: American Artist (New York, 1988) 276.

55. N. Baldwin, Man Ray: American Artist (New York, 1988) 276.

56. Duchamp told Cage that having as second studio “was a way of going underground”, J. Masheck, Marcel Duchamp in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, N.J, 1975) 155.

56. Duchamp told Cage that having as second studio “was a way of going underground”, J. Masheck, Marcel Duchamp in Perspective (Englewood Cliffs, N.J, 1975) 155.

57. S. Swezey, Preface, in Gilmore, op. cit., p. iii.

57. S. Swezey, Preface, in Gilmore, op. cit., p. iii.

60. Interestingly, a 1945 work sometimes thought to be the earliest model for the nude body was sent to forensics and FBI specialists to test and confirm the material as human semen. Ramirez, op. cit., p. 233. How interesting to think that Duchamp, in an erotic act, used the chance design of his ejaculated semen on a piece of paper as a possible “origin” for a body in Etant donnés.

60. Interestingly, a 1945 work sometimes thought to be the earliest model for the nude body was sent to forensics and FBI specialists to test and confirm the material as human semen. Ramirez, op. cit., p. 233. How interesting to think that Duchamp, in an erotic act, used the chance design of his ejaculated semen on a piece of paper as a possible “origin” for a body in Etant donnés.

61. The physical construction of Etant donnés is emphasized by its context in the museum, and also by the fact that it was posthumously re-constructed by others, “put together” again, so to speak.

61. The physical construction of Etant donnés is emphasized by its context in the museum, and also by the fact that it was posthumously re-constructed by others, “put together” again, so to speak.

62. This is Duchamp’s self-written epitaph.

62. This is Duchamp’s self-written epitaph.

Figs. 1-10, 13, 15-16, 18-25 © 2005 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.