1. “Be your own university”— An introduction

It was last June when I decided to go for an interview in the Kunstmuseum (Museum of Art) in Vaduz in Liechtenstein. In my letter of application I mentioned the barriers between different arts as well as the resulting ‘pigeonholing’–to stress the fact that in my mind it is essential to see those barriers not in the sense of limits but rather as challenges. After all I applied for a position which is not exactly tailored to a future high school teacher of History and English. One could interpret this short ‘philosophical interval’ in my letter as a kind of justification–though this was definitely not my aim. Instead I refuse to be labelled as a Historian or English linguist when my interests are distributed among different areas.

“Art is not an escape from life, but rather an introduction to it.”

-John Cage

In my short introductory remark I already mentioned barriers as a central term. I am interested in barriers between different arts and disciplines not in the sense of respecting them but in the sense of blurring. Both, Duchamp and Cage offered me a lot of input through their art, music, philosophy and their blurring of the distinction between art and life. They were in search for a way to escape from traditional painting respectively music. Cage was particularly interested in Zen Buddhism and accordingly invented a new notion of music by using chance as a compositional tool. He was trying to break the traditional barriers between not only theatre, music, dance and fine arts: “I am out to blur the distinctions between art and life, as I think Duchamp was. And between teacher and student. And between performer and audience, etcetera.”

Both Cage and Duchamp revolutionized the common understanding of modern art. They withdrew themselves from commitments to what I call ‘entertaining’ artists who were interested in pleasing a large audience. Duchamp, during his whole lifetime refused to be labelled an artist. “My attitude towards art is that of an atheist towards religion. I’d rather be gunned, kill myself or somebody else than creating art again.” Duchamp was certainly doing art while provocatively refusing it, but here the central message was that he did not want to be categorised in any way. In an interview, he similarly remarked that “a human is a human, as an artist is an artist; only if he is categorised under a certain ‘- Ism’ he can’t be human nor artist.”As I continue my lines of thought at this point it only indicates the beginning of a long walk along these (sometimes invisible) barriers. My ‘philosophical walk’ will be that of an amateur wanderer, someone who got deeply inspired by three outstanding, challenging and at the same time, enigmatic characters.

John Cage first attracted my interest at a lecture in college where our English professor acquainted us with an apparently bright and free mind. When I learned about Cage’s ideals in education I realized that this was the opposite of what we mostly experienced as college students. Reproduction of knowledge is the most common and also most uncomplicated form of assessment, while the written and oral creative output of a student, even when studying languages, lies at a minimum. However, university, as I experienced it, greatly encouraged the meeting with others. It is a place where social exchange can usually take place on a spontaneous basis.

An appealing aspect while working with Cage was the fact that his influence was not just felt in music, but also in visual arts, dance and aesthetic thought in general. He believed that art was intimately connected with our lives and thus not to the museums. Cage stressed the concepts of diversification for unification, of multiversity for university–to express the idea of bringing joy and liveliness into education. He brought into question the term ‘university’ which, he believed, was not encouraging the meeting with oneself. The first rethinking process has to take place in our own minds, thus my title ‘Be your own university.’

My walk will sometimes take place on thin ground, but this interest in border areas would be also in the sense of Cage and Duchamp. Both artists were in search for means to escape tradition. Cage, by inventing compositional tools other than harmony, Duchamp by “unlearning to draw.”In the course of examining those two characters I found many common elements in relation to the mentioned blurring that my final interest focused on this topic. The fact that they shared a lifetime friendship as well as their likewise, but also contrasting ideas and artistic tools represented other interesting elements when studying both characters. Duchamp, more than Cage, created a real challenge for me as his often paradoxical and ironic statements made it hard to ‘complete the puzzle.’ I decided to partly leave the puzzle unfinished–with the slight intention to let my readers finish it.

During the last 50 years, there have been numerous publications on both Duchamp and Cage. I must admit that, for some reasons I intentionally have not read many of them. One reason is that, if I would have, this paper would have ended in a life-time project. Moreover, if the information load is too heavy, one would support unconscious reproduction of different information sources. And I wanted my mind to keep a sense of freedom and space. I gained a great understanding through primary sources as interviews, lectures, texts and letters. Now and then I grabbed books which had only indirectly to do with my topic, such as Rodin’s Art or Gertrude Stein’s Everybody’s Autobiography….in order to keep my mind a bit detached. Thanks to technology it is not much of a problem to get a lively impression of Cage fooling around with the interviewer in a live discussion about his Roaratorio. Those conversations transported the sense of humour and lightness in Cage. I also tried to get familiar with his music–with the rhythms I have heard so much about and still could not guess how they sounded in reality. Sometimes it was indeed an adventurous listening practice and I literally had to keep in mind Cage’s quotation that “disharmony is simply harmony we are unaccustomed to.”

It is worth stating at this point that this project is not intended to be a scientific text in the common sense (as some may have noticed already) Many art historians, at least in German, tend to write in a manner which is apparently designated for a minority target group. It is not the fact that it is impossible for someone interested to understand such a text but that it seems to be an interminable play with words. It appears that they often claim a sense of totality if not universality and thus maintain a clear distinction between art specialists and public. Both Cage and Duchamp have not left behind the impression that their ideas are not accessible to the interested public. After having read some of Cage’s interviews and quotations I almost feel that it is needless to add anything. Many quotations I will cite in the course of this paper could indeed speak for themselves. I guess I just did not have the nerve to leave the space blank in between. Now honestly – I believe that one should first of all enjoy both artists without much scholarship. Cage, in particular, strived to make his work accessible and useful.

This project is best described as an attempt to find my personal way of approaching two artists. I doubt that Duchamp or Cage can be ‘understood’ in the common sense. Duchamp rather left the door open by saying that observers complete works of art themselves. In the end it is up to the audience if a sculpture or a painting is worth surviving. And still, there is something hermetic and mysterious about his work. I must admit that I feel no need to completely uncover its mystery as this would be in contrast to his intentions. The following text will not be scientific in the sense that I do not exclusively intend to give answers but rather challenge new questions. Cage once mentioned in an interview on Duchamp: “‘What did you have in mind when you did such and such?’ is not an interesting question, because then I have his mind rather than my own to deal with.” The paper does not claim comprehensiveness as it, among other things reflects my own experience with both artists.

In order to give hints about what my chapters will be about, I used various quotations which I thought would quite well convey the central topic of the respective essay. However, I refrained from giving too much away and also deliberately missed writing summaries of my ‘essay results.’ The topic is too complex to be packed in a few words and I wanted to allow a space where some doors remain open.

The idea to partly use translucent paper originates from a quotation by John Cage. In his interview with Moira Roth he was asked if his idea of silence had anything in common with Duchamp’s. He answered:

“Looking at the Large Glass (*which is considered to be Marcel Duchamp’s masterpiece), the thing that I like so much is that I can focus my attention wherever I wish. It helps me to blur the distinction between art and life and produces a kind of silence in the work itself. There is nothing in it that requires me to look in one place or another or, in fact, requires me to look at all.”

A glass indeed does not require the spectator to observe the artwork itself, but encourages him to see the environment behind it. In my mind the notion of ‘looking beyond’, that is not being dictated to focus on the work of art itself is a wonderful idea. Through the symbolic use of translucent paper for the initial chapter pages the environment becomes visibly through the pages. As the pages are closed, one can see traces of the next page’s writing. The paper’s contents are blurring in view of the next page’s font. In case my readers believe they are not learning anything new, I invite them to skip parts of the paper.

In History seminars we were taught about the crucial objectivity of a historian. Objectivity is certainly a necessity or at least something to accomplish in this particular area, while at the same time it is almost impossible. Our personal background will, at least subconsciously, make it difficult to maintain objectivity. In view to Cage’s and Duchamp’s overwhelming philosophical input I found it hard to perpetually keep scientific objectivity. I must admit that I did not manage to repress some creative outbreaks. Regarding objectivity, Cage’s introduction to his Autobiographical Statement seems to be quite apt to end my introduction:

“I once asked Arragon, the historian, how history was written. He said, ‘you have to invent it.’ When I wish as now to tell of critical incidents, persons and events that have influenced my life and work the true answer is all of the incidents were critical, all of the people influenced me, everything that happened and that is still happening influences me.”

####PAGES####

2. “There is only one-ism and that is idiotism”

attempt to de-categorise marcel

Paul Cézanne, frequently referred to as the father of Modern Art, once mentioned the line “The great artist is defined by the character he imparts everything he touches.” These words almost ascribe a certain sacredness to the artist. Duchamp’s early oil paintings, in particular the Portrait of the artist’s father or The chess game were apparently influenced by Cézanne. However, as he later self-confidently recalled, those “were only the first attempts at swimming.” At the age of about 25, Duchamp found his own way of self-expression. He more and more distanced himself from what he called “retinal painting” where colour and form of an artwork were overvalued. Oil painting, to his mind, could no longer claim perpetuity. Duchamp believed that true art could only be found in the conceptual space of human mind rather than on the surface of the canvas. This idea reminded me of Kandinsky, who, in his famous Essays on Art and Artists, similarly wrote that it is not so much the form of a work of art which is of significance, but the spirit behind it. Duchamp was one of the first artists who made every effort to desacrifice the common notion of art.

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp

Who is this Marcel Duchamp?

“He neither talks nor looks, nor acts like an artist. It may be in the accepted sense of the word he is not an artist.”

I think of Duchamp (Fig. 1) primarily as an intelligent deceiver. Most of the time he led us believe he was not doing art, as when he was playing chess. Cage commented on him: “All he did was go underground. He didn’t wish to be disturbed when he was working.” In his ‘professional life’ Duchamp wanted to make his own way, accepting a certain isolation. It seems that he often enclosed himself in the solitude of his studio, not telling anybody of his artistic activities. In this way he made a real distinction between his life as artist and his social life. Duchamp wished to be an ‘invisible’ artist as he constantly pretended art did not play a crucial role in his life. He gave up art for chess, experimented with language, eluded us and well kept his mystery. Duchamp’s enigmatic silence led us to questioning and next to the analysis. His silence, among other things, caused curiosity and made him such an interesting character for the public. Joseph Beuys, however, interpreted his silence as ‘silence is absent’ and thus criticised Duchamp’s anti-art concept. He believed that Duchamp’s silence was overrated. Beuys’ statement probably also adverts to his giving up art for chess and writing. On the other hand, Beuys’ artistic goal had much in common with Duchamp’s–he also felt that the action of the artist was more important than the final product. Beuys, by using everyday materials such as fat and felt, also pivotally contributed to the blurring of the distinctions between art and life.

“It’s very important for me not to be engaged with any group. I want to be free, I want to be free from myself, almost.”-Marcel Duchamp

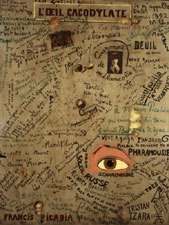

Figure 2

Marcel

Duchamp, Note of 1913

A note, written in 1913, (Fig. 2) reveals an interesting thought, which, in my mind turned out to be central in Duchamp’s artistic life: “Can one make works of art which are not works of art?” As is known, he did make works of art which were up to that point not considered as such–however, he revolutionized the art concept at least for himself. Duchamp wanted art to be intelligent instead of aesthetic. It seems as if he wanted to escape art as practiced in his environment. Duchamp always distanced himself from mainstream artists or what he called “society painters.” However, as we well know, his small, but controversial output exerted a strong influence on the development of the 20th century avant-garde art.

Duchamp was not only interested in art–but in many different areas such as literature, music, mathematics and physics which he tried to incorporate in his art. The fact that he was worrying about problems aside from art, in my mind made him a philosopher. And sometimes history teaches us that a philosopher is more successful than an artist who concentrates too much on art itself. Paradoxical as it may seem, Duchamp did not give up life for art but instead made his life a work of art by living and practicing anti-art. He was probably the first anti- respectively non-artist in history. In an interview he once remarked: “I am anti-artistic. I am anti-nothing. I am against making formulas.” He denied himself as an artist. Some years later he interestingly revised his thoughts by saying that he

“became a non-artist, not an anti-artist…The anti-artist is like an atheist–he believes negatively. I don’t believe in art. Science is the important thing today. There are rockets to the moon, so naturally you go to the moon. You don’t sit home and dream about it. Art was a dream that became unnecessary.”

Anti- or non-artist–in view of Duchamp’s often contradicting statements this question is beside the point. He questioned art as an institution. As Cage mentioned in his 26 Statements Re Duchamp, he “collected dust” while other artists concentrated on being artists. Duchamp refused to lead a painter’s life as he refused to exhibit his works of art. In a letter to an artist fellow, he ironically responded (on the question if he wanted to take part in a public exhibition): “I have nothing to exhibit and, in any case the verb exposer (French word for exhibit) sounds too much like the verb épouser (to marry).” Paradoxically, he did take part in numerous exhibitions of his time…duchamp the intelligent deceiver…Duchamp could obviously live comfor without creating artworks, but never ceased to be an artist of the mind.

Duchamp’s characteristic anti-position was not only expressed in art. Cage, in relation to this, commented: “Marcel was opposed to politics. He was opposed to private property. He was opposed to religion as is Zen. However, he was for sex and for humour.” It seems that what Duchamp refused to do often carried as much significance as what he actually did.

“I am a réspirateur (breather). I enjoy it tremendously.” -Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp had an ironic way of referring to himself in terms as lazy–as a réspirateur or breather–but in fact he was very efficient. In the interview with Cabanne he noted that he preferred breathing to working. When asked how artists manage to make their living, he answered “they don’t have to live. They simply breathe.” According to Duchamp, every breath is itself an artwork without being visually recognizable. He did nothing against the rumour that he had stopped being an artist since the forties–while he was secretly working on Etant Donnés, his last masterpiece, for two decades. Apparently, Duchamp did not even induct his friends into his artistic secrets. Cage commented: “Of course, he was referring to the Etant Donnés, without my knowing that the work existed. He had two studios in New York, the one people knew about, and one next door to it, where he did his work, which no one knew about. That’s why people were able to visit his studio and see nothing going on.” Duchamp managed well to deceive us.

At first sight, Duchamp seemed to be a confirmed anti-materialist. He rarely took a job as he viewed the bourgeois business of having a job and making money as a waste of time. In Paris he worked as a librarian for about two years only to escape from the artistic life there. When he came to America, he gave French lessons in order to bring in enough money to live on. Among his friends, Duchamp was well known for his economy regarding his garments. Cage, in this respect mentioned that Duchamp “was opposed to private property” and recalled the following story:

“Before he married Teeny, he went to visit her on Long Island. Bernard Monnier, her future son-in-law, went to meet Marcel at the station. He said. ‘Where is your luggage?’ Marcel reached into his overcoat pocket and took out his toothbrush and said. ‘This is my robe de chambre.’Then he showed Bernard that he was wearing three shirts, one on top of the other. He had come for a long weekend.”

Art should not be mixed up with commerce, he said–although he could have easily made a fortune from Cubistic paintings. This attitude, however, did not prevent him from buying and selling works of art as a means to earn a living. After having read some of Duchamp’s letters in Affectionately Marcel, I got the impression that he was much more than just an art dealer because of existential reasons. His often dry diplomatic letters to Katherine Dreier and the Arensberg family do not sound much like Duchamp, the réspirateur and anti-materialist. “Budget. Enclose the figures on separate sheet: On one side what I received, on the other side the expenses (I have already paid many things or deposited advances). You will see that on account of the new price of the port-folios, I will be lacking 1221 francs in the end.” Cage, in relation to this said that Duchamp was actually

“extremely interested in money. At the same time he never really used his art to make money. And yet he lived in a period when artists were making enormous amounts of money. He couldn’t understand how they did it. I think he thought of himself as a poor businessman (…) He couldn’t understand why, for instance Rauschenberg and Johns should make so much money and why he should not. But then he took an entirely different life role, so to speak. He never took a job.”

Cage’s statement reveals interesting insights in view to Duchamp’s anti-materialistic attitude (which was of course not truly anti-materialistic) in view to art. Cage indirectly suggested Duchamp’s jealousy of other artists of his time. Without my aiming to give a pseudo-psychological comment, Duchamp apparently resigned making money from art as it did not work out for him. This (well pretended) notion of the anti-materialist fits perfectly into his role as the anti-artist and his withdrawal from painting and the art-world in general, and …it seems as if he once again managed well to deceive us. Duchamp’s self-contradiction must not confuse us, for it is as much one of his trademarks as deception.

Duchamp tried to break with the traditional aesthetic predominance through provocation and irony. He thought that painting as a manual activity increasingly covered the true nature of art by overvaluing retinal aspects. With the invention of his readymades, Duchamp completely changed the direction of modern art. By declaring banal, everyday objects as works of art, he did not only desacrifice art in general, but also the artist himself. “Good taste is repetitive and means nothing else than the rumination of traditional forms of taste.”This certainly meant a provocation for artists who felt related to an art movement such as the Cubists or Abstract Expressionists. Duchamp chose his readymades “on the basis of a visual indifference, and at the same time, on the total absence of good or bad taste.” They were no longer created by the artistic skill, but by the mind and decision of the artist.

Duchamp wanted to break with art as a movement or constitution by turning away from naturalistic modes of expression and inventing his own symbols. Duchamp did not yearn to reach a large audience. Moreover, Marcel was prepared to be misunderstood by the public. He wished to make his own way, accepting a certain isolation: “In 1912 it was a decision for being alone and not knowing where I was going. The artist should be alone…Everyone for himself, as in a shipwreck.” Duchamp, much in contrast to Cage, was never fond of working in a team. He preferred to be an outsider. This outsider role in view to his ‘job’ as an artist, however, must not be confused with the role he took in social life. Duchamp was often described as sociable by his artist fellows, and interviewers “marvelled at how easy it was to talk with Duchamp.”

After a three-months stay in Munich in 1912, Duchamp noted:

“I was finished with Cubism and with movement–at least movement mixed up with oil paint. The whole trend of painting was something I didn’t care to continue. After ten years of painting I was bored with it–in fact I was always bored with it when I did paint, except at the very beginning when there was that feeling of opening the eyes to something new. There was no essential satisfaction for me in painting ever…anyway, from 1912 on I decided to stop being a painter in the professional sense. I tried to look for another, personal way, and of course I couldn’t expect anyone to be interested in what I was doing.”

Apparently, Duchamp tried somehow to escape the traditional notion of being an artist. When Duchamp speaks of trend in relation to art, it sounds unusual as it is frequently associated with fashion. The public art world must have become too superficial and materialistic for him. He was not interested in art in the social sense. Duchamp felt more attracted to the individual mind as such, as he believed most artists were simply repeating themselves. He worked conceptually, putting art “in the service of the mind”, as he would say.

Cabanne:

“You were a man predestined for America.”

Duchamp: “So to speak, yes.”

Things had to change. Duchamp, in a letter to his American friend Walter Pach expressed his dislike for the Parisian art milieu. “I absolutely wanted to leave. Where to? New York was my only choice, because I hope to be able to avoid an artistic life there, possibly with a job that would keep me very busy (…) I am afraid to end up being in need to sell canvases, in other words, to be a society painter.” These lines express crucial reasons for his giving up life as an artist in the professional sense. Duchamp felt incompatible with the French art milieu and wished to escape the prison of tradition where the artist ended up in ‘producing’ paintings in order to earn his living. He felt a strong disapproval of meeting up with other artists. Paris bored him and represented everything he associated with tradition. Duchamp, at this point did not only break with the artistic ties but also with those of his home country. He fled to a country where “they didn’t give a damn about Shakespeare.” His arrival in New York in 1915–Duchamp was 28 at that time–would prove the beginning of a new Duchampian era. By that time, he was already known in America, as his painting Nude descending a staircase caused a scandal at the famous New York Armory Show, an international exhibition of Modern art two years earlier. New York, in contrast to Paris, offered him a “feeling of freedom” and as he said he “loved the rhythm of this town.”Duchamp and America turned out to be the perfect couple.

Duchamp obviously never felt part of an artistic group such as the Dadaists. Moreover, he constantly expressed his dislike for categorisation. From the very outset, he never aimed to describe objects or comment on painting. The more paradox I found the fact that, in most encyclopaedias, Duchamp is either associated with the Cubists or Dadaists. We must rethink the common notion of art in order to get involved with Duchamp. We must free ourselves from convention, categorisation and from -Isms. The following mesostic written by Cage expresses very well Duchamp’s ultimate artistic intention. He wrote it shortly after he had died.

The iMpossibility of TrAdition the loss of memoRy: To reaCh ThEse Two’s a goaL

For those of you who nevertheless feel they have to look up Duchamp’s encyclopaedic biography–(I

am not keeping the secret) See next page.

To refer back to the title: “There is only one -ism and

that is idiotism: John Gillard, a friend, published postcards

with his thoughts–one of them read “There is only one

-ism and that’s a prism.” The idea to change it to ‘idiotism’

came after I was inspired by Kandinsky’s Essays on art and

artists. Kandinsky, like Duchamp often was in the centre

of interest in art criticism. One German art critic called him

the founder of a new art movement called “idiotism.”

Duchamp, Marcel (1887-1968), French Dada artist,

whose small but controversial output exerted a strong influence on the development of 20th-century avant-garde art.

Born on July 28, 1887, in Blainville, brother of the artist Raymond Duchamp-Villon and half brother of the painter Jacques Villon, Duchamp began to paint in 1908. After producing several canvases in the current mode of Fauvism, he turned toward experimentation

and the avant-garde, producing his most famous work, Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 (Philadelphia Museum of Art) in 1912; portraying continuous movement through a chain of overlapping cubistic figures, the painting caused a furor at New York City’s famous Armory Show in 1913. He painted very little after 1915, although he continued until 1923 to work on his masterpiece, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1923, Philadelphia Museum

of Art), an abstract work, also known as The Large Glass, composed in oil and wire on glass, that was enthusiastically received by the surrealists.

In sculpture, Duchamp pioneered two of the main innovations of the 20th century–kinetic art and ready-made art. His “ready-mades” consisted simply of everyday objects, such as a urinal and a bottle rack.

His Bicycle Wheel (1913, original lost; 3rd version, 1951, Museum of Modern Art, New York City), an early example of kinetic art, was mounted on a kitchen stool.

After his short creative period, Duchamp was content to let others develop the themes he had originated; his pervasive influence was crucial to the development of surrealism, Dada, and pop art. Duchamp became an American citizen in 1955. He died in Paris on October 1, 1968.

####PAGES####

3. Silent biography Introduction to John Cage

I thought that the best introduction to John Cage would be an ‘incomplete’ or ‘imperfect’ mestostic. ‘Incomplete’ as I would like to leave enough space for thoughts. Cage described his mesostic technique as follows:

“Like acrostics, mesostics are written in the conventional way horizontally, but at the same time they follow a vertical rule, down the middle not down the edge as in an acrostic, a string spells a word or name, not necessarily connected with what is being written, though it may be. This vertical rule is lettristic and in my practice the letters are capitalized. Between two capitals in a perfect or 100% mesostic neither letter may appear in the lower case. In the writing of the wing words, the horizontal text, the letters of the vertical string help me out of sentimentality. I have something to do, a puzzle to solve. This way of responding makes me feel in this respect one with the Japanese people, who formerly, I once learned, turned their letter writing into the writing of poems (…)”

My mesostics follow a vertical line while the horizontal words consist of different quotations by Cage. Quotations which, in the case of Cage, contain a stronger message than an encyclopaedic biography. Respecting Cage’s ideas such as experience, silence and non-teaching, I would like to leave the reader with the following mesostic. In order to make it easier to identify Cage’s thoughts, I used different type faces. To my astonishment, I found out later that Cage, as a consequence of dealing more and more with the media, also used various font types in various chapters of his book A Year from Monday. In the first chapter,Diary: How to improve the world (you will only make matters worse) 1965, Cage made use of twelve different type faces, letting chance operations determine which face would be used for which statement.

“As far as COnsistency Of I aM here and ThERe is iS NothING To say L SPACE FOR YOUR THOUGHTS SIMPLY GOES HARMONY WEARE PREFER EVERYTHING IS PERMITTED INCONSISTENCY UNCUSTOMED ZERO IS THE BASIC THOUGHT WE NEED NOT FEAR THESE SILENCES.”

Cage, John Milton, Jr. (1912-92), American composer, who had a profound influence on avant-garde music and dance. Born September 5, 1912, in Los Angeles, he studied with the American composers Henry Cowell and Adolph Weiss and the Austrian-born composer Arnold Schoenberg. In 1942 he settled in New York City. Influenced by Zen Buddhism, Cage often used silence as a musical element, with sounds as entities hanging in time, and he sought to achieve randomness in his music. In Music of Changes (1951), for piano, tone combinations occur in a sequence determined by casting lots. In 4’33” (1952), the performers sit silently at instruments; the unconnected sounds of the environment are the music. Like Theatre Piece (1960), in which musicians, dancers, and mimes perform randomly selected tasks, 4’33” dissolves the borders separating music, sound, and nonmusical phenomena. In Cage’s pieces for prepared piano, such as Amores (1943), foreign objects modify the sounds of the piano strings. Cage wrote dance works for the American choreographer Merce Cunningham. His books include Silence (1961), Empty Words (1979), and X (1983).

To refer back to Cézanne’s quotation at the beginning of this chapter–Duchamp proposes the work of art as an independent creation, brought into being a joint effort by the artist, the spectator, and the unpredic actions of chance–a freer creation that its very nature, may be more complex, more interesting, more original, and truer to life than a work that is subject to the limitations of the artist’s personal control.

####PAGES####

4. Passionate encounters Johnand Marcel

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Photograph

of

Duchamp and Cage

John Cage’s and Marcel Duchamp’s (Fig. 3) ways first crossed in 1942. Duchamp, as many European artists, spent the war years in New York. They met in famous Hale House, home of Peggy Guggenheim and Max Ernst which was then well known as the meeting place for European artists in exile. 30 year-old Cage, originally from Los Angeles was invited by his artist-friend Max Ernst to stay in Hale House. When, after a short period, Peggy informed Cage and his wife Xenia who were penniless at the time, to move out of Hale House, Cage “retreated through the usual crowd of revellers until he came to a room that he thought was empty, where he broke down in tears. Someone else was there, though, sitting in a rocker and smoking a cigar. It was Duchamp.” Cage mentioned that “he was by himself, and somehow his presence made me feel calmer. Although I could not recall what Duchamp said to me, I thought it had something to do with not depending on the Peggy Guggenheims of this world.”

Their first encounter reveals interesting aspects of their prospective friendship. Duchamp, the cool smoking type, sitting in a room all by himself, mumbling something amusingly at a desperate stranger. “He had calmness in the face of disaster”, Cage said later. Duchamp could not so easily be disconcerted. The odd encounter scene between Duchamp and Cage somehow conveys Duchamp’s inclination to indifference. Years after they had first met each other, Cage noted in his 26 Statements Re Duchamp: “There he is, rocking away in that chair, smoking his pipe, waiting for me to stop weeping.” Cage obviously experienced Duchamp’s cool indifference first-hand.

Cage, in many interviews, mentioned his friend’s sense for wittiness. As he told Moira Roth, Duchamp was paradoxically “very serious about being amused and the atmosphere around him was always one of entertainment.” He further remarked that “we get to know Marcel not by asking him questions but by being with him.” The reason why Cage did not want to disturb him with questions was that he then would have had Duchamp’s answer instead of his personal experience. Indeed, the concept of experience, deriving from Zen Buddhism, is central in Cage’s philosophy and should not merely be considered in context of his music. He believed that experience, in most respects, was more significant than understanding. It seems that Cage rather wanted to let things happen when spending time with Duchamp. This philosophy has much in common with Cage’s notion of ideal education, but also with his idea of silence and chance in music. Cage was amazed “at the liveliness of Duchamp’s mind, at the connections he made that others hadn’t (…).” These words undoubtedly give evidence of a unbroken Duchamp admirer. When asked what artist had most profoundly influenced his own work, Cage regularly cited Marcel Duchamp.

Duchamp, on the other hand, fondly spoke of Cage as someone full of lightness. “He has a cheerful way of thinking. Not ingeniously (…) He is not acting like a professor or schoolmaster.” I believe that Duchamp did not either want to appear like a schoolmaster, but the respect many people showed towards him, naturally made him less affable. Duchamp, as a consequence of his voluntary artistic isolation, stroke others as aloof.

“Had Marcel Duchamp not lived, it would have been necessary for someone exactly like him to live, to bring about, that is, the world as we begin to know and experience it.” -John Cage

Cage’s respect for Duchamp had blossomed into a sporadic, yet close friendship. In his introduction to 26 Statements Re Duchamp, Cage noted that due to his view “he felt obliged to keep a worshipful distance.” Duchamp’s often mentioned aloof character must have initially had an impact on their friendship. Following Cage’s remarks preceding his 26 Statements, his admiration must have led to dubitation concerning Duchamp. It seems as if he was inapproachable to Cage:

“Then, fortunately, during the winter holidays of ’65-’66, the Duchamps and I were often invited to the same parties. At one of these I marched up to Teeny Duchamp and asked her whether she thought Marcel would consider teaching me chess. She said she thought he would. Circumstances permitting, we have been together once or twice a week ever since, except for two weeks in Cadaqués when we were every day together.”

Cage’s memories leave the impression as though he had long waited for an occasion to ask Duchamp teaching him chess. He later told Calvin Tomkins that Marcel’s quiet way often gave him the feeling that he did not want attention, “so I stayed away from him, out of admiration.” In contrast, it is hard to imagine Duchamp in the role of the passionate admirer. Duchamp rarely spoke about artists that he thought influenced or inspired him. He soon disengaged himself from a model once he grasped it. However, in the case of Raymond Roussel, a writer whose piece Impressions d’Afrique “greatly helped him on one side of his expression”, Duchamp made an exception: “I felt that as a painter it was much better to be influenced by a writer than by another painter. And Roussel showed me the way.”Duchamp found his models less in art than in literature. He was on the way to erase the borders between different arts.

Duchamp, more than Cage, was the type of artist who, due to his mixture of charm and extravagant aloofness, seduced his admirers into an uncritical adulation of his art. He had more of the cool, indifferent type of character who sometimes preferred not to be understood. Though Cage and Duchamp are often discussed in terms of the same artistic circle–along with Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg, their characters appeared to be quite different. Duchamp’s indifference among other things served to keep others from getting to close. I can only to some extent agree with Tomkins who wrote in this respect that “his lack of passionate attachments seemed rather to make him more lighthearted, more alert to everything, and less competitive than others.” Someone who is equally passionate about gathering mushrooms and writing ambitious philosophical texts is in my mind more lighthearted than a professional chess player.

click to enlarge

Figure 4

John Cage

Cage’s sometimes amusing humbleness expressed in his interviews give evidence of his joyful character and his sense of humour (Fig. 4). As Anne d’Harnoncourt, one of Cage’s favourite scholars wrote, he was indeed a delight to observe observing. “Surveying the ground as he walked in a wet field, he found mushrooms; listening to a roomful of silence, he heard his blood circulate in his veins; concentrating on a game of chess, he enjoyed a nearby waterful.” Cage’s interviews, I am thinking in particular of Musicage with Joan Retallack, are interspersed with laughter. Listening to Laughtears–a conversation on Roaratorio, it is not unduly to assert that both the interviewer and Cage laughed their heads off. Though both Cage and Duchamp are frequently described as humorous, Cage’s optimistic and sometimes self-ironic personality probably made him more approachable:

“In connection with my current studies with Duchamp, it turns out I’m a poor chess player. My mind seems in some respect lacking, so that I make obviously stupid moves. I do not for a moment doubt that this lack of intelligence affects my music and thinking generally. However, I have a redeeming quality: I was gifted with a sunny disposition.”

Isn’t it wonderfully amusing to find someone as Cage philosophising about his ‘lack of intelligence’? Duchamp appeared to be more amusing than humorous as a contemporary described him “(…) His blunders are laughable, but he laughs long before you do; as a matter of fact, you laugh at his amusement, not at him.”After having read parts of Duchamp’s letters and interviews, I must add that I found him very amusing. However I would cagely say that his nature of humour was more subtle and black than Cage’s. Duchamp enshrouded himself in a cloud of mystery. After having finished this chapter you will understand what Cage wanted to express by the following mesostic in memory of Duchamp:

Don’t YoU ever want to win? (impatienCe.) How do you mAnage to live with Just one sense of huMor? She must have Persuaded him to smile.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel

Duchamp, Rrose

Sélavy by Man Ray,

1921

As already mentioned in the last chapter, Duchamp was a convinced anti-artist. This attitude was expressed by the adoption of various ‘roles’ such as ‘Duchamp, the dandy’ or ‘Duchamp, the chess player.’ As Roth already wrote in her essay Duchamp in America, Duchamp could be described as a dandy who, as Baudelaire once put it, was obsessed with a “cult of self who used elegance and aloofness of appearance and mind as a way of separating himself from both an inferior external world, and from overt pessimistic self-knowledge.“His dandy appearance also found expression in his ‘roles’ …duchamp the intelligent deceiver… such as Rrose Sélavy (Fig. 5), a self-made, female image inhabiting the idea of an artist-substitute for Duchamp. There is nothing particular in taking on another name – many artists still do. However, he could not so easily take on another sex. Duchamp’s enacted deception was meant as a word play: “(…) Much better than to change religion would be to change sex …Rose was the corniest name for a girl at that time, in French anyway. And Sélavy was a pun on c’est la vie. Duchamp, wearing a seductive fur dressed up as a female and posed for Man Ray’s camera. Rrose Sélavy clearly is the product of an artist who managed to deceive us more than once. After all, he left no indication he was a homo or transsexual.

The most famous role Duchamp however adopted was that of the chess player which again showed himself as the anti-artist. Both Cage and Duchamp devoted much of their energy to playing chess. Duchamp, however, was the more obsessive player. How addicted to chess must one be to neglect one’s bride by spending day and night playing chess during honeymoon? For Duchamp, chess apparently also served as a way to distract himself. Duchamp’s first wife, Lydie, was said to become such annoyed by her groom solving chess problems one night that she got up and glued the pieces to the board. During his 9-months stay in Buenos Aires, Duchamp wrote to a friend: “I feel I am quite ready to become a chess maniac (…) Everything around me takes the shape of the Knight or the Queen and the exterior world has no other interest for me other than in its transformation to winning or losing positions”

For Cage, the goal of winning was clearly beside the point. His motto could be compared to that of the Olympic athletes, “taking part means everything”, under the premise of Duchamp as the antagonist. He was interested in the Buddhist notion of letting things happen, especially when spending time with Duchamp. Cage could apparently confirm Duchamp’s chess addiction – in his interview with Roth he remembered one game of chess where Duchamp got quite angry with him and ‘accused’ him of not wanting to win:

“The only time he disturbed me was once when he got cross with me for not winning a game of chess. It was a game I might have won; then I made a foolish move and he was furious. Really angry. He said ‘Don’t you ever want to win?’ He was so cross that he walked out of the room, and I felt as though I had made a mistake in deciding to be with him–we were in a small Spanish town–if he was going to get so angry with me.”

Duchamp was an excellent chess player, who, in the role of the tireless thinker even made it to the French national team. After his immigration to the United States, Duchamp was ranked among the top twenty-five chess players in the twenties and thirties. In 1932, he published a chess book titled Opposition and Sister Squares Are Reconciled which was devoted “to a very rare situation in the end game, when all the pieces have been captured except for the opposing kings and one or two pawns on each side.” The book gives evidence of Duchamp’s mathematical gift. Cage, on the other hand, used his mathematical ambitions for chance operations in music.

Duchamp and Cage spent more and more evenings together playing chess. “I saw him every night, four nights in a row,“ Cage recalled. What did they do when they were not indulged in their passion? It is certain that they were not talking about each other’s work, according to Cage’s interview with Moira Roth. Meanwhile, they were rather ‘experiencing’ each other simply by spending time together. Cage, rather humble in his statements, often admired his friends’ genius for chess:

“I rarely did (play chess), because he played so well and I played so poorly. So I played with Teeny, who also played much better than I. Marcel would glance at our game every now and then, and in between take a nap. He would say how stupid we both were. Every now and then he would get very impatient with me. He complained that I didn’t seem to want to win. Actually, I was so delighted to be with him that the notion of winning was beside the point. When we played, he would give me a knight in advance. He was extremely intelligent and he almost always won. None of the people around us was as good a player as he, though there was one man who, once in a blue moon would win. In trying to teach me how to play, Marcel said something which again is very oriental, ‘Don’t just play your side of the game, play both sides.’ I tried to, but I was more impressed with what he said than I was able to follow it.”

click to enlarge

Figure 6Photograph

of Reunion

performance, 1968

For Cage, chess apparently served as a pretext to spend time with Duchamp. In 1968, the year of Duchamp’s death, Marcel and his wife were invited to take part in a musical event entitled Réunion by John Cage (Fig. 6). Cage’s idea behind thishappening was that, in his mind, chess contained a finality in itself, as its goal was to win. Cage thus wanted to alienate the game from its ‘purpose’ by distributing sound sources each time movements took place on the chess board. He noted that “the chess board acted as a gate, open or closed to these sources, these streams of music (…). The game is used to distribute sound sources, to define a global sound system, it has no goal. It is a paradox, purposeful purposelessness.” The event consisted of Cage and Duchamp (and later Cage and Teeny) playing chess on stage on a board that had been equipped with contact microphones. Whenever a piece was moved, it set off electronic noises and images on television screens visible to the audience. Cage’s alienation of the chess game from its original purpose is an interesting concept in view to both Duchamp’s and Cage’s understanding of art. Alienation indeed played a crucial role in both artists’ lives. I am thinking now in particular of Duchamp’s readymades and of Cage’s Prepared Piano. Duchamp later amusingly recounted the chess event: “It went very well, very well, it began about eight-thirty. John played against me first, then against Teeny. It was very amusing.” Asked whether there was any music, he replied “Oh yes, there was a tremendous noise.”

Chess brought in no money for Duchamp, but provided richer satisfaction. After all, he was aréspirateur. But why chess? When I learned how to play chess at about 14, I was fascinated about it and eagerly taught it some of my friends. However, I never aimed to perfect it, to rack my brain endlessly about possible combinations. A friend of mine is a passionate chess player and I was quite curious what he found so fascinating about it. He spontaneously answered: “Chess is completely different from other games–it has nothing to do with chance or luck.” I found this statement quite interesting in respect to Duchamp’s use of artistic tools–chance was not only typically Cagean, but in fact used by Duchamp in his music pieceErratum Musical already in 1912, the year Cage was born. For both artists, chance functioned as a means to escape from tradition, taste and conscious intentions. Thus it appears that chess stood in strong contrast to various methods and ideas both Cage and Duchamp used in art. An instinctive compensation? Cage, according to an interview, was interested in mushrooms and chess as a compensation for his concern with chance. This was apparently also true for Duchamp–after all he was well aware of the contradiction between chess and art: “The beautiful combinations that chess players invent–you don’t see them coming, but afterward there is no mystery–it’s a pure logical conclusion. The attitude in art is completely different, of course; probably it pleased me to oppose one attitude to the other, as a form of completeness.”On the other hand, Duchamp believed that art and chess were in fact closer to each other than they seemed. He thought that the game had a visual and imaginative beauty that was similar to the beauty of poetry. Duchamp ended his remarks by saying that “from my close contact with artists and chess players, I have come to the personal conclusion that while all artists are not chess players, all chess players are artists.” When Cage asked Duchamp to write something in his book on the end game, he wrote: “Dear John, Look out! Another poisonous mushroom.” Chess and mushrooms were obviously opposed to the chance operations both Cage and Duchamp used in their art.

What immediately came to my mind when I heard about luck in the course of the chess conversation with my friend, were some thoughts Duchamp wrote to his sister’s husband Jean–on the enquiry, what Duchamp thought about one of his works of art:

“Artists throughout the ages are like Monte Carlo gamblers and the blind lottery pulls some of them through and ruins others (…) It all takes place at the level of our old friend luck. Artists who, in their own lifetime, have managed to get people to value their junk are excellent salesmen, but there is no guarantee as to the immortality of their work. And even posterity is a terrible bitch who cheats some and reinstates others, and reserves the right to change her mind again every 50 years.”

This statement carries a touch of resignation. Duchamp believed that artistic luck had nothing to do with real genius. According to him, “a good artist is just a lucky guy, that’s all.” It seems that Duchamp refused to take part in the ‘artistic lottery’, in the useless competition between artists. Chess, in contrast, justly rewarded those who had a real talent. His passion required him to ‘work hard’ in order to win. Duchamp apparently forgot about his self-made image of the réspirateur when sitting in front of a chess board.

I found it interesting to observe that both Cage and Duchamp had obsessions which cannot immediately be connected to art. Duchamp did not exclusively devote his life to art, as did Cage not concentrate merely on music. The former had a passion for chess, the latter for mushrooms and cooking. Cage was aware of the fact that many people criticised him for not devoting his life to music utterly. When he began his studies with Schönberg, he told his teacher that could not afford the price. Schönberg then asked him if he would devote his life to music and Cage’s answer was “yes.” But–why devoting one’s life to art respectively music if all areas are interrelated? Cage, in this respect said that “I still think I’ve remained faithful. You can stay with music while you’re hunting mushrooms(…)” Both Duchamp and Cage expanded the notion of art into areas which were up to that time clearly separated from art itself. Chess cannot be simply regarded as a pastime for Duchamp, as Cage’s mushrooms and cooking passion were not merely an amusement. They did not only function as a counterbalance to their work as artists. Instead, they were integrated within their thinking and philosophy. Both artists transposed the idea of blurring the distinctions between art and life simply by their way of life. A female friend of Cage interestingly reflected on him:

“The months that followed, which extended into years, afforded me close proximity to both the man and his work. What I came to see was that there was very little difference between the two. That is Cage cooking was Cage composing was Cage playing chess was Cage shopping was…You get the picture. All of his daily activities, from the most sublime to the most mundane, were equally infused with a kind of mindful detachment.”

The way Cage devoted himself to an ‘ordinary business’ such as mushrooms and cooking, is certainly remarkable. Much of his experimental writing and also music was dedicated to his mushroom passion. It seems that whatever Cage experienced in his daily life became raw material for his art. Many of his elaborate remarks in A Year from Monday rather reminded me of an affectionate cook. As in the second part of his Diary: How to Improve the World, where he wrote: “After getting the information from a small French manual, I was glad to discover that Lactarius piperatus and L. vellereus, large white mushrooms growing plentifully wherever I hunt, are indeed excellent when grilled. Raw, these have a milk that burns the tongue and throat. Cooked, they’re delicious. Indigestion.”

Similar to Beuys, who worked with felt, fat and cloth after these materials saved his life after an aircrash, Cage’s interest in mushrooms originated from necessity during the World Depression. He then solely lived on mushrooms for one week and after this experience decided to occupy with them intensely. According to Cage, much could be learnt from music by devoting oneself to the mushroom. “It’s a curious idea perhaps, but a mushroom grows for such a short time and if you happen to come across it when it’s fresh it’s like coming upon a sound which also lives a short time.”Cage found many parallels between mushrooms and music. However, he was well aware of the fact that his mushroom passion, like chess, was in fact in conflict to his idea of chance in music. To leave it to chance whether to eat a mushroom or not could after all end fatal. Mushroom growth is not even determined by chance. They are rather choosy–grow on wet grounds only. Like Duchamp, Cage published a book on his passion in cooperation with two other mycologists. And – surprisingly, he did make money with his mushroom passion. Cage once appeared on an Italian show as mushroom expert and won 6000 US dollars by answering ‘mushroom questions’ correctly

Mushrooms fired Cage’s imagination. His idea was that everything on earth should be audible because of vibration–including mushrooms. “I’ve had a long time the desire to hear the mushroom itself, and that would be done with a very fine technology, because they are dropping spores and those spores are hitting surfaces. There certainly is sound taking place.”Proceeding on this assumption, he made explorations on which sounds further the growth of which mushrooms. Besides being one of the founders of the Mycological Societyin New York, Cage taught a course called ‘Mushroom Identification’ at the NY School for Social Research. One lecture he held dealt with the ‘sexuality’ of mushrooms:

“We had invited a specialist from Connecticut, who had cultivated a certain species of mushroom, a Coprinus, in very large quantities to study their sex. In his lecture, he taught us that the sexual nature of mushrooms wasn’t so very different from that of human beings, but that it was easier to study. He explained that there are around eighty types of female mushrooms and around one hundred and eighty types of males in one species alone. Some combinations result in reproduction, while others do not. Female type 42, let’s say, will never reproduce with male type 111, but will with certain others. That led me to the idea that our notion of male and female is an oversimplification of an actually complex human state.”

Would you have thought of mushrooms in terms of female and male? I would not and besides enjoying myself immensely, I am continually amazed at Cage’s affectation of details. He had an extraordinary ability to exploit these new insights and incorporate them into his artistic thinking. And yet at the same I am asking myself how one can possibly have such a playful mind in order to connect sounds with mushrooms…I wonder if Cage was aware of his mushroom passion as something which many people would simply consider absurd if they did not study him thoroughly. To my astonishment I found the answer on the very last page of Cage’s first book Silence. Cage’s thoughts prove that he was hardly someone worldly innocent.

“In the space that remains, I would like to emphasize that I am not interested in the relationships between sounds and mushrooms any more than I am in those between sounds and other sounds. These would involve an introduction of logic that is not only out of place in the world, but time-consuming. We exist in a situation demanding greater earnestness, as I can testify, since recently I was hospitalised after having cooked and eaten experimentally some Spathyema foetida, commonly known as skunk cabbage. My blood pressure went down to fifty, stomach was pumped, etc. It behoves us therefore to see each thing directly as it is, be it the sound of a tin whistle or the elegant Lepiota procera.”

“Isn’t cooking all about mixture and letting individual flavours hold our attention?”

-Anne d’ Harnoncourt

In the late 70s, Cage, after serious health problems, began a macrobiotic diet on the advice of John Lennon and Yoko Ono. The idea of the macrobiotic diet is to make a shift from animal fats to vege oils. What fundamentally distinguishes the macrobiotic diet from other health programs is that, rather than consisting of a fixed list of foods to be consumed or avoided, it provides a structure which applies to the whole range of available choices, an orientation which many adherents of the diet extend to a whole cosmology. For Cage, macrobiotics undoubtedly meant more than just cooking or eating. However, he did not take the diet too seriously–he used herbs and spices which he enjoyed. In the short introduction to his macrobiotic recipe collection in his Rolywholyover – A Circus Box, Cage wrote: “The macrobiotic diet has a great deal to do with yin and yang and from finding a balance between them. I have not studied this carefully. All I do is try to observe whether something suits me or not.” Strictly following a recipe would not sound much like Cage–reading his recipes for chicken or beans indeed sound a bit like his notations in music–they allow enough room for the performer’s interpretation.

Cage’s discovery of macrobiotics is no coincidence–with its oriental origin and its application of yin and yang, the macrobiotic diet fits in very well with both Zen and with the temperament of Cage. He believed he had already been affected by the ideas of the diet before he actually started it: “I accepted the diet you might say aesthetically before I accepted it nutritionally.” As Harnoncourt’s interesting quotation (“Isn’t cooking all about mixture and letting individual flavours hold our attention?”) suggests, cooking has a great deal to do with music where individual sounds hold our attention. After studying Cage, I cannot suppress the impression that he could have utilized all daily activities in his art. Cage’s kitchen probably was one big sound studio:

“In all the many years which followed up to the war, I never stopped touching things, making them sound and resound, to discover what sounds they could produce. Wherever I went, I always listened to objects. So I gathered together a group of friends, and we began to play some pieces I had written without instrumental indications, simply to explore instrumental possibilities not yet catalogued, the infinite number of sound sources from a trash heap or a junk yard, a living room or a kitchen…we tried all furniture we could think of.”

Cage was astonished by the positive results of the macrobiotic diet. “Your energy asserts itself the moment you wake up at the beginning of the day. It remains constant. It doesn’t go up and down, it stays level, and I can work much more extensively. I always had a great deal of energy, but now it is extraordinary. At the same time,” he added, “I’m much more equable in feeling; I’m less agitated.” His improvement so amazed him that he kept up the diet from that time onwards and frequently recommended it in interviews:

“Now, however, after, say, four years of following the macrobiotic diet, my health has so greatly improved that I would seriously advise almost anyone who would lend me an ear to make a shift in diet from animal fats to vege oils, to exclude dairy products and sugar, to ‘choose’ chicken only if it actually is a chicken, that is, free from injected hormones, agribusiness, etc., to eat fish, beans and whole grains, nuts and seeds, and vege s with the exception of theSolanaceae (potatoes, tomatoes, egg-plant, and peppers)”

Macrobiotics also inspired Cage to a growing concern with nature and ecological matter. Big business and agribusiness, he stressed, damage our meat, vege and water supplies. Food which he mostly advised in special books of recipes include proper preparations for brown rice, zucchini, beans and chicken. In connection with the museum project calledRolywholyover Circus, John Cage published various macrobiotic recipes. Four of them I will include at the end of this chapter.

“I try to discover what one needs to do in art by observations from my daily life. I think daily life is excellent and that art introduces us to it and to its excellences the more it begins to be like it.” –John Cage

Cage’s devotion to macrobiotics and mushrooms are interesting insofar, as they once again witness his contribution to the blurring of the distinction between art and life. As already suggested, Cage’s passions cannot be simply regarded as pastimes or, as in the case of cooking, in the context of a human necessity–though Cage began his macrobiotic diet on medical grounds, thus out of a necessity. We certainly do not get past spending time to prepare our daily food–nevertheless it is a question of how we deal with those daily routines. Cooking was as much a part of Cage’s life as composing music and poetry. Once Cage managed the shift from ordinary cooking to macrobiotics, he consciously devoted more time to what can be called the ‘act of cooking.’ This is at least the impression he left behind in his elaborate recipe descriptions. As Kuhn wrote in her essay, it was hard to distinguish Cage from his work: “Cage cooking was Cage composing was Cage playing chess was Cage shopping was…”

Cage, in contrast to Duchamp, frequently made his friend the theme in his writings as well as music. Cage’s ‘homages to Duchamp’ give evidence of the importance of this friendship for him. In his book, A Year from Monday he dedicated 26 Statements on Re Duchamp to his artist friend. The Statements are among other things Cage’s reflections on Duchamp’s artistic methods: “The check. The string he dropped. The Mona Lisa. The musical notes taken out of a hat. The glass. The toy shot-gun painting. The things he found. Therefore, everything seen–every object, that is, plus the process of looking at it–is a Duchamp.”Cage continued his reflections on Duchamp in the second and third part of his Diary: How to Improve the World. In the late 40s, Cage wrote the music for a Duchamp sequence in Hans Richter’s famous avant-garde film Dreams that Money Can Buy. The song is called Music for Marcel Duchamp. In his M–writings ’67-’72, Cage composed several mesostics in memory of Marcel. The following mesostic was written shortly after Duchamp’s unexpected death in 1968. Cage remarked, “it was a loss I didn’t want to have.”

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride Stripped

Bare by Her Bachelors, Even,

1915-23

Undoubtedly, Duchamp’s work and philosophy lived on in the work of John Cage – as in the case of his visual work titled Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel (1969). The work consists of a Plexiglas field on which one may find letters and fragments of words. Anne d’Harnoncourt wrote about it that “Cage characteristically sought to maintain both multiplicity and transparency by setting eight sheets of clear plastic printed with words in stands so that the viewer peered through them; and if he wasn’t careful, his gaze passed beyond them.” The work is indeed very reminiscent of Marcel Duchamp’sLarge Glass (Fig. 7). As the title suggests, Cage did not want to say anything about his artist friend and thus subjected words to chance operations. He possibly wanted to leave the spectator with language fragments in order not to take him in completely. There is no point in attempting to ‘resolve’ Not Wanting to Say Anything about Marcel. I believe it is a homage to a very good friend.

Another interesting work which Duchamp apparently inspired him to, was the box which I already mentioned in connection with his macrobiotic recipes. Duchamp, in his artwork called Boite, gathered together small reproductions of his artworks unbound in boxed form rather than in an album or a book. So did Cage: Rolywholyover – A Circus is a reflecting box which was designed in consultation with Cage himself. The publication accompanied with a major exhibition at The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles conceived of by Cage as a “composition for museum.” The box is an artwork fully in keeping with his philosophy. It contains a wide range of materials, printed in different formats–such as reprints of texts that Cage found useful and inspiring. The texts can be read in any order. The box also includes reproductions of works by Cage, musical scores, recipes, advice on healthy eating and photography. As Cage said in discussing the box,

“The world is vast, give the impression that the materials are endless.” -John Cage

Despite Cage’s intense occupation with Duchamp, he always remained a somehow mysterious mind. In the foreword to his alphabet in X-writings ’79-’82, Cage reflected on Satie, Joyce and Duchamp–three artists who greatly inspired him. Cage is quite explicit about his ‘goals’ in respect to those three artists–namely that he is not interested in ‘understanding’ in the sense of giving ultimate answers. His humbleness nevertheless gives evidence of an exceptional bright and free mind. In relation to Joyce’s masterpieceFinnegan’s Wake he wrote:

“When I was in Ireland for a month last summer (…) many Irishmen told me they couldn’t understand Finnegan’s Wake and so didn’t read it. I asked them if they understood their own dreams. They confessed they didn’t. I have the feeling some of them may now be reading Joyce or at least dreaming they’re reading Joyce. Adaline Glasheen says: ‘I hold to my old opinion. Finnegan’s Wake is a model of a mysterious universe made mysterious by Joyce for the purpose of striking with polished irony at the hot vanity of divine and human wishes.’ And she says: “Joyce himself told Arthur Power, ‘What is clear and concise can’t deal with reality, for to be real is to be surrounded with mystery.’ Human kind, it is clear, can’t stand much reality. We so fiercely hate and fear our cloud of unknowing that we can’t believe sincere and unaffected, Joyce’s love of the clear dark–it has got to be a paradox….an eccentricity of genius.”

I was impressed by Joyce’s quotation–for reality is indeed often mysterious and inexplicable. In Cage’s interview on his Roaratorio–An Irish Circus on Finnegan’s Wake, Cage remarked that “Joyce didn’t mean Finnegan’s Wake to be understood, he meant it to be a piece of music.” We tend to question everything which is unfamiliar with. Asking questions is one thing but expecting precise answers is another. In relation to Duchamp, Cage thought that asking him questions was the wrong tactic. He had no special intentions when spending time with him. I believe that we can learn a lot from Cage when trying to study Duchamp. Asked on how Cage would circumscribe his friendship with Duchamp, he answered:

“If, for instance, you go to Paris and spend your time as a tourist going to the famous places, I’ve always had a feeling you would learn nothing about Paris. The best way to learn about Paris would be to have no intention of learning anything and simply to live there as though you were a Frenchman. And no Frenchman would dream of going to, say, Notre Dame.”

Nevertheless, there remained a hermetic aspect of Duchamp’s work. Cage once spoke to Marcel’s wife, Teeny Duchamp about this: “I said, ‘You know I understand very little about Marcel’s work. Much of it remains very mysterious to me.’ She answered “It does to me, too.” We must be satisfied with what we are offered by Duchamp–otherwise we will end in a never ending helix. John and Marcel simply enjoyed each other’s presence, without much talking about their work. In order to contribute something to your enjoyment – my suggestion is that you try Cage’s Roast chicken before you continue with the next chapter. In case you are not hungry you will enjoy reading them.

‘Passionate encounters’, this chapter’s motto, is dedicated to the personalities of both Cage and Duchamp as well as their friendship – a friendship which was very much formed by their passions. Though chess initially functioned as a pretext for Cage to spend time with Duchamp, it became an important and enjoyable common amity experience. While writing about chess, I found many parallels in Cage’s passions repertoire and thus tried to examine it also in view to the central notion of the essay–the blurring of the distinction between art and life. Moira Roth’s interview with John Cage has helped me a lot to get an insight into their nature of friendship. However, this only gives a one-side impression and as Duchamp’s documented statements on Cage were comparatively rather rare, it is far from completing the puzzle. I am writing this with the humble precaution of a historian who was taught to take all possible historical resources into account.

As I am writing these lines, my thoughts lead me to Duchamp, the perpetual intelligent deceiver. I am thinking of the Duchamp who was never willing to give away too much. While listening to the last beats of Cage’s Music for Marcel Duchamp I am constantly reminded of the Duchamp who managed well to surround himself with mystery. One should be a clairvoyant rather than a historian.

Recipes À LA JOHN CAGE

“Cage’s scores for music, scores for prints, recipes for chicken, all exist for realization by the artist in real time, and he invited his audience (or his dinner guests) to realize that listening, cooking, and eating are also creative acts.” -Anne d’Harnoncourt

John Cage’s recipes are an interesting experience in view to his whole philosophy. His cooking advices are precise and clear, but far from elitist. They give evidence of his pedagogical gift not to impose his ideas on anybody. Cage, for example did not use the imperative form of “you do …(such and such)”, but instead used the self-referential “I” when explaining the cooking procedures. Interesting also, that his recipes are be inspired by various cultures. The following recipes should offer a possibility to ‘experience’ John Cage. I found it quite interesting what Cage said about experience:

“I think that there is a distinct difference between…. I think that the most pointed way to put this distinction is by using the word “understanding” as opposed to “experience.” Many people think that if they are able to understand something that they will be able to experience it, but I don’t think that that is true. I don’t think that understanding something leads to experience. I think, in fact, that it leads only to a certain use of the critical faculties. Because…say you understand how to boil an egg. How will that help you in cooking zucchini? I’m not sure. One could make the point more dramatically by saying, “How will that help you to ride horseback?” But that probably goes too far. I think that we must be prepared for experience not by understanding anything, but rather by becoming open-minded.”

Roast Chicken

Get a good chicken not spoiled by agribusiness. Place in Rohmertopf (clay baking dish with cover) with giblets. Put a smashed clove of garlic & a slice of fresh ginger between legs and wings and breasts. Squeeze the juice of two & three lemons over the bird. Then an equal amount of tamari. Cover, place in cold oven turned up to 220°. Leave for 1 hour. Then uncover for 15 minutes, heat on, to brown. Now I cook at 170°, 30 minutes to the pound. Or use hot mustard and cumin seeds instead of ginger. Keep lemon, tamari or Braggs and garlic. Instead of squeezing the lemon, it may be quartered then chopped fine in a Cuisinart with the garlic & ginger (or garlic, cumin & mustard). Add tamari. The chicken & sauce can be placed on a bed of carrots (or sliced 3/4-inch thick bitter melon obtainable in Chinatown)

Brown Rice

Twice as much water as rice. If you wish, substitute a very little wild rice for some of the brown rice. Wash or soak overnights then drain. Add a small amount of hijiki (seaweed) and some Braggs. Very often I add a small amount of wild rice. Bring to good boil. Cover with cloth and heavy lid and cook for twenty minutes over medium flame, reduce flame to very low and cook thirty minutes more. Uncover. If it is not sticking, cook it some more. If it is sticking to the bottom of the pan, stir it a little and then cover again and let it rest with the fire off. When you look at it again after ten minutes or so it will have loosened itself from the bottom of the pan. Another way to cook rice: using the same proportion of rice, bring to a boil and then simply cover with lid without the cloth, reducing the fire to low. After forty-five minutes, remove from fire but leave lid on for at least 20 minutes.

BEANS

Soak beans overnight after having washed them. In the morning change the water and add Kombu (seaweed). Also, if you wish, rosemary or cumin. Watch them so that they don’t cook too long, just until tender. Then pour off most of the liquid, saving it, and replace it with tamari (or Braggs). But taste first: you may prefer it without tamari or with very little. Taste to see if it’s too salty. If it is, add more bean liquid. Then, if you have the juice from a roasted chicken, put several teaspoons of this with the beans. If not, add some lemon juice. And the next time you have roast chicken, add some of the juice to the beans. Black turtle beans or small white beans can be cooked without soaking overnight. But large kidney beans or pinto beans can be cooked without soaking overnight. But large kidney beans or pinto beans, etc. are best soaked (So are the others.) Another way to cook beans which has become my favourite is with bay leaves, thyme, garlic, salt and pepper. You can cook it with some kombu from the beginning. I now use the “shocking method.” See Avelines Kushi’s book. And now I’ve changed again. A Guatemalan idea: Bury an entire plant of garlic in the beans without bothering to take the paper off. Cook for at least 3 hours.

Chick-Peas (Garbanzos)

Soak several hours. Then boil in new water. Until tender. They can then be used in many ways. 1. Salad. Make a dressing of lemon or lime with olive oil (a little more oil than lemon), sea salt and black pepper, fresh dill-parsley, and a generous amount of fine French mustard (e.g., Pommery). 2. Or use with couscous having cooked them with fresh ginger and a little saffron. 3. Or make hummous. Place, say, two cups of chick-peas with one cup of their liquid in Cuisinart. Add a teaspoon salt, lots of black pepper, a little oil and lemon juice to taste. Add garlic and tahini. Now I no longer add salt, but instead a prepared gazpacho.

####PAGES####

5.

“If that’s art, I’m a Hottentott”

“Everyone is doing something, and those who make things in a framed canvas, are called artists.” –Marcel Duchamp

Duchamp was apparently interested in a general conception of art. What do we call art? Or better what is not considered as art? Can we define works of art which are not works of art–as Duchamp already questioned. Moira Roth, in relation to this wrote that “if one is Duchamp the answer is probably no, although he did ‘make’ works which were not immediately works of art.” Otherwise, these questions are not easy ones to answer–on the contrary, they provoke a number of new question marks. Where is the border between art and non-art? And then–how do we define non-art?

As a historian, I was first of all interested in a definition of art. And as it turned out I had to dig a bit into philosophy. Art originally derived from Sanskrit and meant ‘making’ or ‘creating something’. Plato took up the definition and went one step further by distinguishing artists into two categories: those who are productively creating objects such as architects or carpenters and those who are restricted to the already existing or imitation (what he calledMímesis). Plato honoured the craftsman more than the artist as he believed that the former was oriented at the ideas of the mind, while the latter was simply creating an imitation of the already existing. According to Plato, the painter distanced himself from the truth–in order to attain it, one has to leave all appearances behind and should not duplicate it by a sort of reflection. In the Middle Ages, art (Ars) was generally interpreted as a production and design of everyday objects. It was a skilled trade which was thus never valued under just aesthetic aspects. If we strictly stick to this definition, an artist is nothing else than a workman. And as Duchamp said in an interview, everyone of us is somehow a workman–in different areas of course. Artworks have not always been valued under just aesthetic characteristics–as this short historical outline teaches us.