click to enlarge

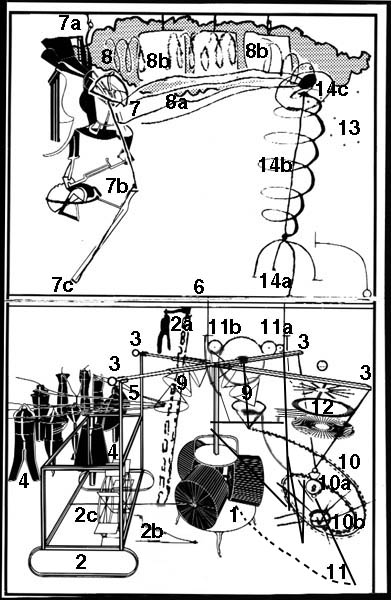

Figure 1.

Marcel Duchamp’s masterpiece is The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even (The Large Glass), 1915-1923 (Figure 1). With his notes, which the artist stated were part of the piece, it stands as the most influential artwork of our century. Duchamp said that the two plate-glass panels which hold the work were accidentally broken, then carefully repaired.

The greater our familiarity with the sources for this work, the stronger the sense that this must have been the most fortuitous accident in the history of art; or not an accident at all. In any case, The Large Glass, visualized in its unbroken state, does not make nearly the poetic sense that it does in its broken state. Duchamp’s own response to interviewers is not at odds with this evaluation. This article will talk generally of the Jarry/Duchamp connection and present evidence suggesting a conscious breaking of the glass.

* * *

Marcel Duchamp once said, “Rabelais and Jarry are my gods, evidently”.Barely any of Rabelais’ imagery can be found with any specificity or consistency in Duchamp’s work and notes, but ideas and imagery adapted from Alfred Jarry’s writings crop up regularly in many of his most characteristic concoctions. Sometimes we see the material straight up, thinly disguised, sometimes in the form of either ingenious or obvious inversions. An example of inversion occurs in a Duchamp note treating an image from a pivotal scene in Jarry’s science fiction novel, The Supermale. A five-man bicycle team of inconceivable potency is engaged in a cosmic race, sometimes exceeding the speed of light, with a train on a ten-thousand-mile elliptical course. When they reach the apogee, which represents the fourth dimension, Jarry describes a tower, “shaped like a truncated cone.” In Duchamp’s writings for the large glass, with their “heaps of notes on the fourth dimension,”he makes reference instead to a “conical trunk.” Vis à vis breakage, the Jarry scene ends with the symbolic penetration of the fourth dimension’s barrier, pictured as the shattering of a large barrel which has magically appeared as the racers complete their turn. “The cowcatcher of the locomotive hit [the barrel] like a football, spattering the rails and the track with a little water and sheaves of roses.” Roses owe their presence to the Supermale’s virgin inamorata Ellen Elson, the sole female passenger on the train. Her entire car had earlier been mysteriously covered by “red roses; enormous, full-blown, and as fresh as if they had just been picked. Their perfume spread through the stillness of the air…”

The English title for The Large Glass is The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even. In Jarry’s first novel, the autobiographical Days and Nights, a licentious young artist’s model named Huppe is itching to entertain five lovers in the studio where she poses. One of the chosen, introduced as “the Jewish eunuch Severus Altmensch,” is understandably hesitant. Sengle, the Jarryesque hero of the novel, dreams up a ruse to permit all present to see the naked body of Severus. His objective is to discover “whether he lacked so much as to be a eunuch or merely enough to prove him a Jew.” He proposes a game “to decide who would pose nude on the dais.” Then, “without cheating, although Sengle might have predicted the result, the lot fell upon Severus Altmensch. Who refused to comply. Sengle held him by the shoulders — with his fingertips –and Huppe stripped (him)…” The inversion here is that a male (“bachelor”) is being stripped by a female (“bride”). In a number of Jarry’s novels hyper-sexual females who are not brides are referred to as such. Another figurative foretaste of Duchamp, here sans inversion, is the central presence of one “bride” and multiple “bachelors,” with copulation their sole raison d’être. And we meet in the person of the Jewish eunuch — the stripping reveals as much — a viable forerunner to Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Sélavy, who was born when the artist had himself photographed as a female. Castration is naturally implied when a male becomes female. Recall, too, that Duchamp’s first idea for Rrose involved turning himself into a Jew.

This orgy scene takes place in a “studio below the oasis of a great lamp.”The short chapter ends with the naked troupers scampering: “And the six disappeared in the smoke of the great lamp, whose glass was cracked … they rushed to their clothes, barefoot across the cracks.” Appearing in 1897, this is the first of three crucial scenes in separate Jarry novels describing “stripped” participants in a whirl of sexual jouncing, accompanied by images of cracked or shattered glass. The second occurs in Messalina, 1900, the third in The Supermale, 1902.

In Chapter One of Messalina, the heroine, wife of Emperor Claudius Caesar, takes on all comers in a lowly brothel from nightfall to sun-up, then “[closes] her cell-door last of all, later even than her servant, still consumed with desire.”Duchamp’s “Bride”, according to his notes, is “basically a motor” and “in perpetual motion.”

Chapter Two begins with Claudius rising at dawn, “when Messalina slept at last,” then entering “the quadrangular, glass-paned study which rose above the roofs of the palace…” On the next page we learn that most of the Emperor’s courtiers are also his wife’s lovers. In the same chapter, Jarry describes a cameo of the Empress “that was copied and preserved by Rubens.” We read that “according to this cameo … [she is] not beautiful, in fact; but then the fire in her eyes has been put out in the unliving stone! And surely beauty is only a convention.(7) Or perhaps a form that is called beautiful is but a vase for passion, and one preferably unblemished, uncracked even, as it is itself of the purest transparency.” Though Jarry here equates beauty with an uncracked and transparent vase, in the next scene his promiscuous heroine, soon to be a “bride,” is associated with an image of shattering glass. She contemplates the magnificent landscape outside her window “as though admiring herself in a mirror…Suddenly she burst into sobs, and in her room it was as though the great mirror of Sidon glass had shattered across the mosaic floor –a sparkling arena of powdered specular stone! –or as though the pearls of the portrait were unstrung and the beauty of Messalina flooded over the ground in a thousand fragments.”

Chapter Three, Book II, of Messalina is titled THE ADULTEROUS NUPTIALS. It describes a “marriage” in which the Empress (who, of course, is already married) is to be the “bride.” This chapter, with its central figure the unquenchable Messalina, certainly relates to the drama Duchamp described in his notes to the glass, with an axial bride surrounded by her bachelors.

Relevant to Duchamp’s “Stripped Bare,” Jarry’s heroine, “altogether naked” for most of her appearances, declares at one critical point, “But I have given you my whole life! I love you, Silius! My body, which you do not reject. . . will you also peel off my skin…?” The bride of the adulterous nuptials is offering herself to be stripped bare indeed by one of her “bachelors.”

In The Supermale, the American Ellen Elson, as eager in her clean-cut way as the notorious Roman Empress, says towards the end of a non-stop around the clock sexual marathon, “I’m not naked enough. Couldn’t I take this thing off my face?” She makes reference to her sole bit of apparel, a pink plush driver’s mask meant to hide her identity from the peeping scientist busy keeping score for the bettors. In the chapter titled AND MORE, she has just helped Marcueil, the Supermale, achieve an imposing record of eighty-two consummations in twenty-four hours. Marcueil leaves the room briefly, pleased with having accomplished his goal.But the instant he returns,

“a supple body, still warm from his embrace, wrapped itself about him and pushed him onto the bed of fur. And the young woman’s breath murmured, in a kiss that made his ears buzz: ‘At last we’re through with the betting to please… Now let’s think of ourselves. We haven’t yet made love. . . for pleasure.’ She had double-bolted the door. Suddenly, near the ceiling, a windowpane shattered, and the glass showered down on the rug.”

Thus ends the chapter.

click to enlarge

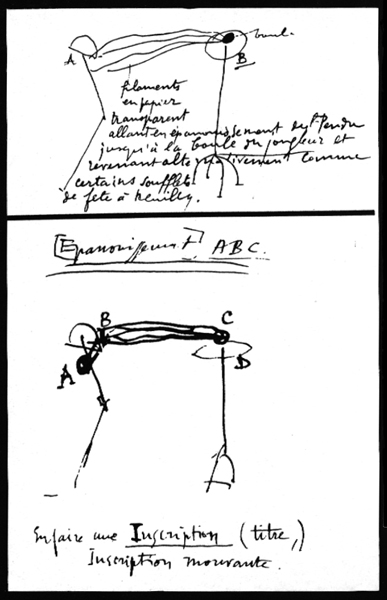

Figure 2.

Before delving further into broken glass, we’ll detour to a glass-free passage from Jarry which depicts a sexually amenable machine-bride.In 1902, the same year as The Supermale, Jarry’s article for La Revue Blanche titled Wife-beaters tells of a “matrimonial agent who was at the same time a large rubber manufacturer” who made “spouses of elastic rubber available for two-thousand francs per specimen, three thousand with made-to-order head.”We learn that “honeymooning in their company is incomparable” and that “one enters into communication with them by means of a valve.” Duchamp’s bride seems to share this handy feature with Jarry’s honeymooning spouse. Under the heading Compression in Duchamp’s posthumously published notes for the glass we find, with the artist’s idiosyncratic punctuation: “cones in elastic metal (resembling udders) passing drop by drop the erotic liquid which descends toward the hot chamber, onto the planes of slow flow. to impregnate it with oxygen required for the explosion. the dew of Eros.” An additional possible connection suggests itself here. Duchamp’s perfume bottle festooned with Rrose Sélavy’s face is titled BELLE HALEINE, EAU DE VOILETTE 1921. (Figure 2) One of the English translations for belle is ‘rubber’ as in “rubber game” or “winning game.” French/English puns were a specialty with the artist, as were games. Jarry’s honeymooning bride is made of rubber, and his Supermale’s sexual marathon was a winning game.

Jarry and Duchamp circle around the same exotic terrain obsessively. They share a marvelously specific stereotype of woman as sexually insatiable. In Jarry’s case she is sometimes flesh and blood, sometimes a machine; in Duchamp’s case, always a machine.

* * *

The Large Glass, with its notes, features a distinctive pattern of sexual motifs combining the ideas of virginity, sexuality and machinery. There are machines that resemble the living, a bride who “reveals herself as nude,” who, although he calls her “basically a motor,” “becomes a sort of apotheosis of virginity,” or “must appear” as same. A little later she is simply “this virgin” with an “intense desire for the orgasm,” whose “reservoir will end at the bottom with a liquid layer.” His bachelor machine section includes a description of “the bottles: Great density and in perpetual movement…(oscillating density). It is by this oscillating density that the choice is made between the three crashes. It is truly this oscillating density that expresses the liberty of indifference”“…after the 3 crashes = Splash.”

Jarry, in a passage from Days and Nights (1897), shows a similar collision of motifs. These include the idea of “virgins,” nakedness, love-making, “glass wall,” a “liquid sea,” “machines [which] resemble the living” and “which move, oscillating in the waves…” Two pages earlier, Jarry introduced the subject of “a glass shopfront.” Here are two passages without the intervening text:

Sengle,…thought first of looking for a ditch or a glass shopfront for the temporarily blind men to topple into…

I have been unable to bring Micromegas back to life or join the quotinoctial circling of virgins around the enclosure.

There is an inscription upon the wall stating that whoever passionately kisses his Double through the glass, for them the glass comes to life at one point and becomes a sex, and person and image make love through the wall, whether by the will of the immortal gods or the artifice of some skillful man who has constructed machines to resemble the living, and which move, oscillating in the waves and to the island’s libation, on the other side of the glass.

Compare this with Duchamp’s ‘shop window’ soliloquy dated 1913, published in A l’Infinitif:

The question of shop windows

To undergo the interrogation of shop windows.

The exigency of the shop window

The shop window proof of the existence of the outside world

When one undergoes the examination of the shop window, one also pronounces one’s own sentence. In fact, one’s choice is “round trip.” From the demands of the shop windows, from the inevitable response to shop windows, my choice is determined. No obstinacy, ad absurdum, of hiding the coition through the glass pane with one or many objects of the shop window. The penalty consists in cutting through the glass pane and in feeling regret as soon as possession is consumated. Q.E.D.

Of all the images common to both passages, the critical parallel is between the idea of “coition through the glass pane,” as Duchamp puts it, and Jarry’s “person and image make love through the [glass] wall.”

There are, as well, numerous subsidiary affinities: Jarry has, “a glass shopfront for the temporarily blind men to topple into…” Duchamp has, “The shop window proof of the existence of the outside world.” And the title of his 1917 magazine was The Blind Man,with its celebratory Blindman’s Ball. Jarry pictures for us “the…circling of virgins,” Duchamp’s notes describe the Bride as “a sort of apotheosis of virginity,” and her “Sex Cylinder” features “Heat produced by rotation.” Jarry: “I stand naked against the glass wall…standing in the liquid sea.” Duchamp: “The Bride reveals herself as naked,” and “The reservoir will end at the bottom with a liquid layer… This liquid layer will be contained in the oscillating bathtub (hygiene of the Bride.)” Jarry’s “…by the will of the immortal gods or the artifice of some skillful man who has constructed machines to resemble the living…” sounds like a precise prediction, twenty years before the fact, of the notes for The Large Glass and the skillful man who wrote them.Jarry tells us that the machines made by this man “move, oscillating in the waves … on the other side of the glass,” a harbinger of Duchamp’s Bride in her “oscillating bathtub” and his bachelor machine, with its “oscillating density.”

click to enlarge

Figure 3.

From Duchamp’s ‘shop window’ soliloquy we learn that “one’s choice is “round trip.” This almost certainly relates to his known interest in the androgyne, a male-female creature. His L.H.O.O.Q., from 1919, (Figure 3), is a reproduction of the Mona Lisa to which he has added a mustache and beard. The title, when the letters are pronounced in French, becomes “She has a hot ass,” which readily reminds us of Jarry’s famous homosexual bravado and occasional cross-dressing. Two years later, in harmony with Jarry’s line, “I…gaze at my image glued close to me…” Duchamp himself cross-dressed and began his habit of hiding behind his female double, Rrose Sélavy, signing many of his important works with her name. It is quite easy to view The Large Glass, in addition to its other significations, as a picture of Duchamp “kissing” his Double through the glass.

To the cast of characters cited thus far as likely models for Duchamp’s bride and bachelors, add Adele from The Supermale. She is first among “the seven prettiest harlots in Paris” who have been hired by Marcueil to assist him in attaining a new record for virility. Prior to being locked out and preempted by the amateur Miss Elson, we find the prostitutes arguing among themselves over who would “go” first. Virginie informs the others that she was told “we’ll be ‘put through’ in alphabetical order.” A few lines later we read, “Let’s congratulate the first ‘bride,’ said all six, making deep curtsies to Adele.” As in Messalina, a lady with an accommodating sexuality is referred to as a bride. Unlike the scene in the earlier novel, this arrangement is the reverse of the configuration in The Large Glass. The prostitutes were hired to be many “brides” for one bachelor.

In the same novel, the five-man bicycle team racing the speeding locomotive enlightens us regarding “the machine with 5 hearts” in Duchamp’s notes for The Large Glass.

“Perpetual Motion Food” energizes Jarry’s cyclists, whose interminable race symbolizes and prefigures the sexual marathon to follow; “Love Gasoline” energizes Duchamp’s bride and he describes the Bachelor Machine’s “bottles” as “in perpetual movement.”

Jarry speaks of the gears of the cycle, Duchamp of the “desire gears” and “lubricious gearing.”

Early in the novel, we read of Marcueil’s physical attack on an imposing “female” machine, literally shattering it to pieces as he utters, “Come, Madame.” Duchamp’s 1912 machine-like painting Bride is called to mind, as well as a Green Box note from that period describing “this nude bride before the orgasm which may (might) bring about her fall.” Also, this orgasm/fall idea can be tied to Marcueil’s firm belief, later in the story, that he has killed Ellen with his frenzied lovemaking, as well as to Messalina’s execution for indiscriminate bed-hopping. The Love Machine, title of the final chapter of The Supermale, again calls to mind Duchamp’s concept of a mechanical bride and bachelors and their “love gasoline.” Messalina and Ellen could be called, in common parlance, sex-machines; Duchamp’s Bride is literally that. Yet notwithstanding unremitting desire and sexual athleticism, his Bride, like Jarry’s heroines, is described a virgin.

* * *

Jarry’s biographers are in agreement that each of his heroines can be easily identified as symbolizing his mother, with whom he was obsessed. Jarry’s ultimate “dramatic situation” is “to perceive that one’s mother is a virgin.” The reason for his repeated association of sexual intercourse with the breaking of glass is plainly related to a fantasy he shared with his readers in which his mother is a virgin whom he would break in. In his novel L’Amour Absolu (Absolute Love) written in 1899, a young man resembling the author makes love to his “virgin” mother, then kills her. Duchamp’s alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, gives us that basic plot in a few words: “…an incesticide must sleep with his mother before killing her…” (…un incesticide doit coucher avec sa mère avant de la tuer…) . Both the Jarry story and Duchamp’s encapsulation remind us of Duchamp’s “virgin” bride, whose orgasm might bring about her fall. Any doubt that Jarry means his “bride” vanishes when we read in this novel, “I am the Son, I am your Son, I am the spirit, I am your husband, in all eternity, your husband and your son, oh pure Jocasta,” connecting his mother to Oedipus’ mother/wife. Oedipus was blinded as punishment for making his mother his bride; Jarry describes “a glass shopfront for the temporarily blind men to topple into…” His imagery of making love through a glass wall may well signify the breaking of his mother’s hymen. Duchamp’s soliloquy ends, “The penalty consists in cutting the pane and in feeling regret as soon as possession is consummated. Q.E.D.” The “regret” and the “penalty” seem to both connect with Rrose’s mention of “an incesticide.” The pun possibilities, which include ‘incest’, ‘insect’, ‘insecticide’ and ‘suicide’, work equally well in French and English. Q.E.D., abbreviation for which was to be demonstrated, in all likelihood points to the immanent construction of The Large Glass.

* * *

Considering Jarry’s persistent association of frenetic coupling with cracked or shattering glass, and Duchamp’s words from 1913, “The penalty consists in cutting the pane…,” the suspicion arises, though obviously only a theory, that the two thick glass plates of The Bride Stripped Bare By Her Bachelors, Even were not broken accidentally, as advertised.

click to enlarge

Figure 4.

Remember that Tu m’, 1918, (Figure 4), Duchamp’s last painting as such, features a zigzagging trompe l’oeil rent cutting the plane of the picture, as well as a brush handle, a bolt, and three safety pins physically puncturing the canvas surface — an unprecidented violation of the heretofore sacred face of a painting. This could be an indication that Duchamp’s intentions, conscious, or half-conscious, were already preparing for a later, more ambitious breaking of a two-dimensional work’s plane. By 1918, the year of the painting, he was well into work on The Large Glass.

The story given to the world regarding this famous breakage is devoid of details and has sufficient time and space for the act to have been done surreptitiously. We’re told that more than four years passed before the breakage was discovered by the Glass’s owner, another two months before the artist was let in on the secret. A 1956 television interview of Duchamp has the interviewer, J.J. Sweeney, opening with : “So here you are, Marcel, looking at your Large Glass.” Duchamp responds, “Yes, and the more I look at it the more I like it. I like the cracks, the way they fall. You remember how it happened, in 1926, in Brooklyn?”

Duchamp errs slightly here regarding the year. The Glass was not packed up until January of 1927 after its premiere showing at The Brooklyn Museum. Also, since by all accounts it wasn’t discovered broken until 1931 in Connecticut, “it happened…in Brooklyn” can be an assumption at best. If it occurred in transit between Brooklyn and Connecticut, with the truckers unaware, or at the least uncommunicative, why assume Brooklyn? Possibly to divert attention from Connecticut. To further muddy things, Duchamp’s handwritten caption on the back of the Glass states that it was broken in 1931, even though he repeatedly told interviewers that it broke on its way to Connecticut years before. Is it possible that his caption on the artwork is more reliable than his words? If so, then Connecticut would have been the scene of the breakage.

Continuing Duchamp’s reply: “They put the two panes on top of one another on a flat truck, not knowing what they were carrying, and bounced for sixty miles into Connecticut, and that’s the result! But the more I look at it the more I like the cracks: they are not like shattered glass. They have a shape. There is a symmetry in the cracking, the two crackings are symmetrically arranged and there is more, almost an intention there, an extra — a curious intention that I am not responsible for, a ready-made intention, in other words, that I respect and love.”

On the same subject, Duchamp gave this account to Pierre Cabanne in 1966: “While I was gone, it was shown in an international exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum. The people who sent it back to Katherine Dreier weren’t professionals; they were careless. They put the two glasses one on top of the other, in a truck, flat in a box, but more or less well packed, without knowing if there was glass or marmalade inside. And after forty miles, it was marmalade. The only curious thing was that the two pieces were one on top of the other, and the cracks on each were in the same places.’

Cabanne: The cracks follow the direction of The Network of Stoppages, it’s astonishing all the same.

Duchamp: Exactly, and in the same sense. It constitutes a symmetry which seems voluntary, but that wasn’t the case at all.

Cabanne: When one sees The Large Glass one doesn’t imagine it intact at all.

Duchamp: No. It’s a lot better with the breaks, a hundred times better. It’s the destiny of things.

Cabanne: The intervention of chance that you count on so often.

Duchamp: I respect it; I have ended up loving it.

Jarry, no less than Duchamp, seemed to love Chance, l’accident. He had invented a new physics, for which he coined the word ‘Pataphysics,’ containing nothing less than an alternate hypothesis for the workings of the universe. These workings depended ultimately on “purely accidental phenomena.” Duchamp identified to a startling degree with this concept and coinage in his notes and attitudes. For example, he describes his 3 Standard Stoppages, of 1913, as “casting a pataphysical doubt on the concept of a straight line as being the shortest route from one point to another.” And once, for a friend, he signed a photograph of himself, “Yours Pataphysically (Bien pataphysic a vous), Marcel Duchamp.”

click to enlarge

Figure 5.

The fervor of Duchamp’s remarks about the breakage is unprecedented. We never hear him raving about any piece or aspect of his work the way he does about this. One explanation might be that he felt free to be so openly enthusiastic about this because it was not his doing. But it may be instead that given what the world was told, he felt free to rave about the one part of the idea that he personally liked most. When we consider that earlier, two other important pieces on thick plate glass were also reported to have been accidentally shattered (The 9 Malic Moulds, 1914-1915, and To Be Looked At With One Eye, Close To, For Almost An hour, 1918 — Figure 5) — both, according to my thesis, influenced to a substantial degree by Jarry — the case for a discreet intentional breaking becomes stronger. Duchamp’s account of how The 9 Malic Moulds was broken may shed light on the “astonishing” symmetry that Cabanne and others have commented upon: “[The glass] was cracked when I brought it here to America in 1915. I showed it to somebody and it was leaning against a rocking chair which rolled back, so the splinters were not scattered at all, the floor was carpeted, it stayed in shape, as it is today. All I had to do was to pick it up very carefully between two other glasses, so that it would not change shape, and would keep like that, which it has for the last forty years.”

A chess master, and self-described “very meticulous man,” would seem an unlikely victim of such an accident, let alone three of them. His description of this accident raises questions. To break a thick plate glass panel on a carpeted floor, one would have to be particularly unlucky or clumsy. Yes, if you were careless enough to leave the piece under the runner of a rocking chair, a person sitting and inattentively rocking backward or forward over it might break it, carpeted floor notwithstanding. But what Duchamp describes is different. Rolling an empty chair back, causing the glass to fall from its leaning position to a flat position on a carpeted surface, would seem insufficient to cause such thick glass to shatter. A look at the configuration of cracks on the piece only reinforces this skepticism.

click to enlarge

Figure 6.

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Wanted, 1923.

The stories offered are of accidents. My questioning Duchamp’s veracity will be seen as decidedly late-in-the-day when we consider his own famous all-purpose disclaimers, such as, “Every word I tell you is stupid and false,” and “All in all I’m a pseudo, that’s my characteristic.” We also have the famous self-portrait titled With My Tongue In My Cheek, 1959, (Figure 6), a second self-portrait as a “Wanted” felon, 1923,(Figure 7), and a third as the very devil.In the Cabanne interview, given two years before Duchamp’s death, we find him blatantly ignoring the truth. When the interviewer, harking back to the twenties, brings up his decision to stop painting, Duchamp reminds him that the Glass “was far from the traditional idea of the painter, with his brush, his palette, his turpentine, an idea which had already disappeared from my life.”

Cabanne: Did this break ever bother you?

Duchamp: No, never.

Cabanne: And you never had a longing to paint since then?

Duchamp: No,… Never… All that disgusted me.

Cabanne: You never touched a brush or pencil?

Duchamp: No. It had no interest for me. It was a lack of attraction, a lack of interest.

Duchamp is leaving out the palette and all the brushes and turpentine that he used in executing the meticulously painted backdrop for the Etant Donnés, knowledge of which was kept from the world while he lived. Later in the interview, Duchamp goes out of his way to close any conceivable loophole to the truth.

Cabanne: You’re the first in art history to have rejected the idea of painting…

Duchamp: Yes. Not only easel painting, but any kind of painting.

click to enlarge

Figure 8.

It is noteworthy that the cracks in The Large Glass are the part that Duchamp seems to be most proud of. When having it photographed for reproduction in The Box in a Valise, 1935-41, (Figure 8), Duchamp tells Dreier to make sure that the photographer shoots the piece so that every crack in the glass is visible. He wrote, “I hope you won’t have too much trouble with Mr. Coates about photographing the glass. It seems important to me to have the black background as well as the white one… The black is to help outlining the cracks in the glass, the white outline is to help outline each group painted on the glass (chocolate grinder etc…….) …Each item (including cracks) on the glass shall be printed from half-tone cuts cut out and leaving the cellophane perfectly transparent.” This means that in the concise 16″ x 10″ reproduction in the Box, Duchamp, with the help of hundreds of tiny stencils, will reproduce every tiny shard of broken glass that state-of-the-art photography could reveal. If the cracks were not part of the original thinking, he has certainly welcomed them into the family with all the rights and privileges accorded the children of his own brain. And it may be significant that he treated the cracks on the other two broken works in similar ways reproducing them for the Box. For The 9 Malic Moulds: “A labor-intensive detail that is almost invisible…is the pattern of “original” cracks in the glass, reproduced by scratching with an etching needle.” For To Be Looked at With One Eye…..: “…the lines of the cracks in the glass have been strengthened in ink.”

Duchamp to Arturo Schwarz: “I never finished The Large Glass, because after working on it for eight years I probably got interested in something else; also I was tired.” To Cabanne on this subject: “…it became monotonous, it was a transcription, and toward the end there was no invention. So it just fizzled out.”But though he may have stopped the work in 1923 because he was bored by it, he seems, in 1965, only a few years before the end, to have been still very enthusiastic about its cracks. In fact, nothing in the hundred page Cabanne interview elicits equal exuberance. Furthermore, his fondness for broken glass can be traced back to the era of the Arensberg salon when he was still at work on the piece. It was there that he declared that “a stained glass window that has fallen out and lay more or less together on the ground is of far greater interest than the thing conventionally composed in situ.”

One last sign that may point away from l’accident is that in his early notes, composed either before or roughly concurrent with the three shatterings, Duchamp makes reference to “the 3 falls,” and repeatedly to “the 3 crashes.” Coincidentally, of the seven pieces which he made with or on panes of glass, three were “accidentally broken.” Coincidentally, in three Jarry novels, highly sexual activity is accompanied by cracking or shattering glass. Eventually the sheer number of coincidents seems to make a statement.

Duchamp never names a second person witness to any of the accidents. In the case of The 9 Malic Moulds, as mentioned, he was showing it to “somebody.” Regarding To Be Looked At With One Eye…, I have come across no description of the circumstances surrounding its breaking. And The Large Glass itself, we’re told, was discovered broken years after it was delivered to Katherine Dreier. Neither she nor anyone else is named as having been aware of the breakage when it occurred. Was the shattered glass of the two large panels mute as the heavy packing crate was carried from the truck and set down in Dreier’s storage space? Was she in attendance for the event? Was anyone there besides the truckers? Was an insurance company of the truckers or of Dreier or of the Museum ever notified?

Dreier is the one person identified by Duchamp in connection with any of the breaks. She was a “formidable woman who considered herself an artist,” and who was known for her “organizational skills.” She was to all appearances obsessed with Duchamp. She followed him to Buenos Aires in 1918 even though it is clear that they were never romantically involved.Duchamp made the laborious repairs over a period of two months in her home in West Redding, Connecticut. Dreier has been described as a “demanding presence” for Duchamp during the entire thirty years of their acquaintance. Nor was the connection left to die with her — she had named him executor to her will.

Perhaps Duchamp looked to Jarry’s works for ‘instructions,’ even to the point of breaking three thick plate glass pieces. Telling the world that The Large Glass and the others were broken accidentally would then be just another of his famous hoaxes. True, in all of art history we have never heard of an artist who secretly destroys major works, telling the public a story of accidents, all with the intention of laboriously repairing them. But then, we have never before had an artist who works on a major work for twenty years in total secrecy — the intricate Etant Donnés, with its moving parts, its artificial lighting, and its fifty page construction manual — while claiming publicly that he had completely stopped making art, leaving his survivors to deal with the complications of its posthumous debut. This was a man who thrived on secrets and who was obviously more interested in posterity’s decision than in the instant gratification most artists hunger for. “Wait for posterity,” was one of his mantras. Another was, “I found it amusing.” Conceivably the artist capable of the drawn out ruse of the Etant Donnés, with its awesome logistics, might have been just the artist capable of three sudden gestures — three falls — kept equally secret.In the one case, it takes twenty years to construct one hidden piece; in the other, it takes seconds to destroy three public ones. It would be a neat inversion indeed.

* * *

AFTERWORD

In 1959 Duchamp agreed to be “a satrap” in the College of Pataphysics, the “Parisian band of zealots devoted to perpetuating (and often distorting) Jarry’s philosophical pranks.”But, in spite of his having identified Jarry as one of his two “Gods,” by 1965 he had been fairly quiet about a Jarry connection for about forty-five years. In 1965, possibly inspired by mixed signals which the artist himself had periodically put on the record about Jarry, the Swiss art historian Serge Stauffer sent the question, “Was Alfred Jarry an influence?” Duchamp answered, “Not directly, only in an encouragement found in Jarry’s general attitude toward what passed for Literature in 1911.” Actually, Jarry had already been in his grave four years by 1911. That year may have come to Duchamp’s mind because it was the year in which Jarry’s influential Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll, Pataphysician was published posthumously. This was hailed by Apollinaire as “the publishing event of the year.” It is clear that back in 1914 Duchamp did not mind confiding to his notes, and to whomever might read them, his intense interest in Jarry. In his art-defining formula of that year, consisting of just four words, the most revealing word is Jarry’s coinage merdre, by then famous in the art world and beyond as marking the end of one era in the arts, and the beginning of another. It is the only one of the four words not found in the French dictionary, or in any other. The equation reads,

Arrhe est à art que merdre est à merde. In English it would be something like ‘Deposit is to art as shitte is to shit.’

Even by 1918, he is still relaxed about the possibility of someone connecting the writer to himself. Tu m’ of that year is essentially an abstracted illustration of the pivotal scene in The Supermale where the racing five-man bicycle team reaches the fourth dimension, the turning point of the race. There is a Jarry sentence there that would work well as a caption for Tu m’, Duchamp’s last painting for a wall: “It was revolving on its own axis, corkscrewing through the air just above the ground in front of us, while a furious wind was sucking us toward its funnel.”

Duchamp obviously came to reverse this openhandedness about Jarry. He may have decided that the connection was too good to broadcast. Or it may have been that admitting as an influence the same writer who was being increasingly lionized by the likes of Picasso, Dali, Ernst, Miró, Magritte (as well as by virtually all of the Futurists, Surrealists and Dadaists) would have been out of character for the secretive and independent person he was becoming. This reading is consistent with Robert Lebel’s recollection of a remark made by his friend, Marcel Duchamp: “In a shipwreck, it’s every man for himself.”

* * *

HE HAS NICE TEETH, HE PROBABLY ONLY CHEWS BROKEN GLASS AS A RULE…

…THE CHANDELIER SWAYED, THE PICTURE FRAMES TREMBLED, AND NEAR THE CEILING, A PANE OF GLASS VIBRATED.

…A FIST, CUIRASSED WITH RINGS BUT WHICH BLED NEVERTHELESS, SMASHED IN THE PANE.

SUDDENLY, NEAR THE CEILING, A WINDOW-PANE SHATTERED, AND THE GLASS SHOWERED DOWN ON THE RUG.

The Supermale

…THE GREAT MIRROR OF SIDON GLASS HAS SHATTERED ACROSS THE MOSAIC FLOOR…

Messalina

…THE SIX DISAPPEARED IN THE SMOKE OF THE GREAT LAMP, WHOSE GLASS WAS CRACKED. AND SCANDALIZED…THEY RUSHED TO THEIR CLOTHES, BAREFOOT ACROSS THE CRACKS.

Days and Nights

Notes

1. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp (New York: Henry Holt and Co.), 73.

1. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp (New York: Henry Holt and Co.), 73.

2. Duchamp in 1966 to Pierre Cabanne: Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (New York: Viking Press, 1971).

2. Duchamp in 1966 to Pierre Cabanne: Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp (New York: Viking Press, 1971).

3. Jarry’s “…a little water and sheaves of roses,” whose “perfume spreadthrough the stillness of the air,” would seem to connect with Duchamp’sperfume bottle labeled with a photograph of the artist as Rrose Sélavy[BELLE HALEINE, EAU DE VOILETTE — Beautiful Breath, Veil Water]of 1921. The title’s second word could remind us that the Supermaledreams of Ellen transformed into Helen of Troy (Hellene is French forGreek) during a post coitum animal triste. (P. 72). Haleine canalso be used in the phrase “Tenir en Haleine” (“to keepin working order” or “in a working mood”). Ellenneeded to stay in the mood and in super working order for 82 consummationsin 24 hours. Rrose, who Duchamp once described as an old whore, withher calling card advertising herself as a specialist in “precision assand glass work” fits well with this good “working order” sense and alsowith the Greek part of the thesis, since anal intercourse is known as”the Greek way” in both English and French slang. A second meaning forvoilette is fall, so that EAU DE VOILETTE ties to water-fall,as in Duchamp’s title Given: 1. The Waterfall; 2. The IlluminatingGas, which in turn ties to the falling water on the Supermale’sestate. It is the power generated by this water, at the novel’s end,that supplies the voltage that electrocutes him as punishment for having”loved” Ellen.

3. Jarry’s “…a little water and sheaves of roses,” whose “perfume spreadthrough the stillness of the air,” would seem to connect with Duchamp’sperfume bottle labeled with a photograph of the artist as Rrose Sélavy[BELLE HALEINE, EAU DE VOILETTE — Beautiful Breath, Veil Water]of 1921. The title’s second word could remind us that the Supermaledreams of Ellen transformed into Helen of Troy (Hellene is French forGreek) during a post coitum animal triste. (P. 72). Haleine canalso be used in the phrase “Tenir en Haleine” (“to keepin working order” or “in a working mood”). Ellenneeded to stay in the mood and in super working order for 82 consummationsin 24 hours. Rrose, who Duchamp once described as an old whore, withher calling card advertising herself as a specialist in “precision assand glass work” fits well with this good “working order” sense and alsowith the Greek part of the thesis, since anal intercourse is known as”the Greek way” in both English and French slang. A second meaning forvoilette is fall, so that EAU DE VOILETTE ties to water-fall,as in Duchamp’s title Given: 1. The Waterfall; 2. The IlluminatingGas, which in turn ties to the falling water on the Supermale’sestate. It is the power generated by this water, at the novel’s end,that supplies the voltage that electrocutes him as punishment for having”loved” Ellen.

4. Chapter Three, Book I.

4. Chapter Three, Book I.

5. Coincidentally, in Duchamp’s posthumously unveiled Etant Donnés,a nude woman, with her legs spread, holds high, almost dead center,a glass lamp. The lush painted backdrop could be either a paradise oran overly idyllic oasis.

5. Coincidentally, in Duchamp’s posthumously unveiled Etant Donnés,a nude woman, with her legs spread, holds high, almost dead center,a glass lamp. The lush painted backdrop could be either a paradise oran overly idyllic oasis.

6. Jarry introduces the novel with a quote from Juvenile’s Satires,writing of the historical Messalina, which may point to Jarry’s knowninterest in androgeny: “…she stayed till the end, always the lastto go, then trailed away sadly, still with a burning hard-on, retiringexhausted, yet still far from satisfied.”

6. Jarry introduces the novel with a quote from Juvenile’s Satires,writing of the historical Messalina, which may point to Jarry’s knowninterest in androgeny: “…she stayed till the end, always the lastto go, then trailed away sadly, still with a burning hard-on, retiringexhausted, yet still far from satisfied.”

7. Duchamp: “Taste is habit.” Cabanne, Dialogues With Marcel Duchamp.

7. Duchamp: “Taste is habit.” Cabanne, Dialogues With Marcel Duchamp.

8. His intent was to prove the viablity of his opening line, also the first words of the novel: “The Act of love is of no importance, since it can be performed indefinitely.” Again we think of Duchamp’s bride, “basically a motor,” “in perpetual motion.”

8. His intent was to prove the viablity of his opening line, also the first words of the novel: “The Act of love is of no importance, since it can be performed indefinitely.” Again we think of Duchamp’s bride, “basically a motor,” “in perpetual motion.”

9. Duchamp’s notes tell of the Bride’s “intense desire for the orgasm.”

9. Duchamp’s notes tell of the Bride’s “intense desire for the orgasm.”

10. A more comprehensive account of this connection was published in an earlier essay. See William Anastasi, “Jarry in Duchamp,” New Art Examiner (October 1997).

10. A more comprehensive account of this connection was published in an earlier essay. See William Anastasi, “Jarry in Duchamp,” New Art Examiner (October 1997).

11. Note that by implication the cheaper model is a ready-made item as well as a machine-wife.

11. Note that by implication the cheaper model is a ready-made item as well as a machine-wife.

12.Paul Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Notes (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980).

12.Paul Matisse, Marcel Duchamp, Notes (Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1980).

13. Jarry too seems to have had a soft spot for indifference. Here is an exchange between his characters Fear and Love:

13. Jarry too seems to have had a soft spot for indifference. Here is an exchange between his characters Fear and Love:

Fear: Your clock has three hands. Why is that?

Love: Nothing could be more natural, nothing simpler. The first marks the hour, the second urges on the minutes, and the third, forever motionless, points to the eternity of my indifference.

From “Visits of Love,” Chapter VIII, Fear Visits Love (London: Atlas Press, 1993).

14. Published with Henri-Pierre Roche and Beatrice Wood.

15. Nobel laureate Octavio Paz connected Jarry’s later posthumously published novel to Duchamp with these remarks: “The best commentary on the Large Glass is Ethernites, the last book of the Gestes et opinions du Docteur Faustoll. A doubly penetrating commentatery because it was written before the work was even conceived.”

16. Duchamp’s relief Etant Donnés: la Chute d’Eau et le Gaz d’Eclairage , 1948-49, shows a nude figure with one leg lifted. The opening between the legs resembles a notch made by an axe rather more than it does an anatomically faithful vagina. The upper torso has an unquestionably female left breast, but a right one more to a male’s proportions.

17. Jarry’s sparse ouevre of paintings includes at least one that he signed “Ubu,” the name he gave to his best known invented character who served also as his notorious alter ego.

18. Anne d’Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine, eds., Marcel Duchamp(Philadelphia: TheMuseum of Modern Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973).

19. As with the other famous breakages, we are given no named witness.

20. Consciously or otherwise, imagery from Jarry may have contributed to Duchamp’s story. At the climax of The Supermale, following the moment when Ellen asks for MORE after having withstood 82 rapid-fire consummations, the chapter ends with: “Suddenly, near the ceiling, a windowpane shattered, and the glass showered down on the rug.”

21.Corroboration can be found as well in the remarks of his friends. H.P. Roche: “I watch Normans like Duchamp carefully … I know that I can be had by him.” John Cage: “…he was a wonderful man, and I was very fond of him. But he did love secrets.” William Anastasi, Jarry, Joyce, Duchamp and Cage (Catalogue to the Vienna Biennale, 1973).

22. Ecke Bonk, Marcel Duchamp, The Box in the Valise (New York: Rizzoli Press, 1989), 200.

23. Ibid., 206.

24. Ibid., 247.

25. Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (London: Thames & Hudson, 1997), 146.

26. Cabanne, Dialogues With Marcel Duchamp, 65.

27. Dickran Tashjian, Henry Adams and Marcel Duchamp: Liminal Views of the Dynamo and the Virgin (speech at The Whitney Museum of American Art, 26 April 1976), 22.

28. Tomkins, Duchamp, 209.

29. Tomkins, Duchamp, 180.

30. In Duchamp’s notes for The Large Glass, there are mysterious allusions to an “instantaneous state of rest,” an “extra-rapid State

of Rest” and a “twinkle of the eye.”

31. Michel Sanouillet, “Marcel Duchamp and the French Intellectual Tradition,” in Marcel Duchamp (Philadelphia: The Museum of Modern Art and Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1973).

32. At the age of 72, looking back on his long career, Duchamp said, “Eroticism is a subject very dear to me…in fact, I thought the only excuse for doing anything was to introduce eroticism into life. Eroticism is close to life, closer to life than philosophy or anything like it; it’s an animal thing that has many facets and is pleasing to use, as you would use a tube of paint.” Given this outlook one can easily guess that his use of the word “arrhe” points more to the sexual than to any other place on the compass. From a primitive male point of view, a deposit of semen is the goal of each act of sexual intercourse. This could not have been overlooked by Duchamp, the punster responsible for “Have you already put the hilt of the foil in the quilt of the goil?” Therefore, one interpretation of his formula must be: “my way of saying fucking corresponds to everyone else’s way of saying art as Jarry’s way of saying shit corresponds to everyone else’s way of saying shit.” – or more succinctly: “My fucking is to your art as Jarry’s shit is to your shit.” See William Anastasi, “Jarry in Duchamp,” New Art Examiner (October 1997).

33.The Supermale, p 32. An analysis of this connection appears in William Anastasi, “Duchamp on the Jarry Road,” Artforum (September, 1991).

Fig.1~8 © 1999 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

1. Marcel Duchamp, Pontus Hulten, ed., 1993. Why is Marcel Duchamp´s Bicycle Wheel Shaking on Its Stool?

1. Marcel Duchamp, Pontus Hulten, ed., 1993. Why is Marcel Duchamp´s Bicycle Wheel Shaking on Its Stool? 2. I am grateful to Francis M. Naumann for pointing out that fours years prior to this ‘errand,’ Duchamp intended to sell L.H.O.O.Q. to Louise and Walter Arensberg. In a letter dated 16 July 1940, Duchamp writes from Arcachon, France: Une autre chose dans la même genre est l’original de la Joconde aux moustaches (1919) / Pensez-vous que $100 soit trop pour la dite Joconde (Something else in the same category is the original of the Mona Lisa with a mustache (1919) / Do you think that $100 would be too much for the so-called Mona Lisa ). The Arensbergs are not known to have acquired the work. Arturo Schwarz in his The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, vol. 2 (New York: Delano, 1997) lists the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York and the collector Mary Sisler as previous owners of L.H.O.O.Q. As for its current status, it is now in a private collection in Paris. As yet unaccounted for is the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, which on a label on the work’s verso is credited (as Matisse Gal.) for loaning the work to the Museum of Modern Art’s traveling exhibition The Art of Assemblage which was on display in New York from 10 October – 12 November 1961.

2. I am grateful to Francis M. Naumann for pointing out that fours years prior to this ‘errand,’ Duchamp intended to sell L.H.O.O.Q. to Louise and Walter Arensberg. In a letter dated 16 July 1940, Duchamp writes from Arcachon, France: Une autre chose dans la même genre est l’original de la Joconde aux moustaches (1919) / Pensez-vous que $100 soit trop pour la dite Joconde (Something else in the same category is the original of the Mona Lisa with a mustache (1919) / Do you think that $100 would be too much for the so-called Mona Lisa ). The Arensbergs are not known to have acquired the work. Arturo Schwarz in his The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, vol. 2 (New York: Delano, 1997) lists the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York and the collector Mary Sisler as previous owners of L.H.O.O.Q. As for its current status, it is now in a private collection in Paris. As yet unaccounted for is the Pierre Matisse Gallery, New York, which on a label on the work’s verso is credited (as Matisse Gal.) for loaning the work to the Museum of Modern Art’s traveling exhibition The Art of Assemblage which was on display in New York from 10 October – 12 November 1961.