1. The Odyssey of Stoppages

1a. Three Standard Stoppages

click to enlarge

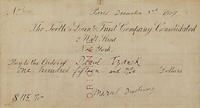

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp,

Three Standard Stoppages, 1913-14

Scholars have already carefully underlined that the operative procedure described by Duchamp for the execution of Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14) (Fig. 1) seems to be unreliable. By means of experimental proofs we have the evidence that it is seemingly “unobtainable,” somewhat like Duchamp’s Stoppages. Furthermore, an inspection of the work at MoMA (Museum of Modern Art in New York City) shows two tacks at the opposite extremities of the thread on the backside of each canvas. These tacks seem to exclude what the famous note contained in the Green Box, (also entitledThe Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even, as the project it accompanies), definitively describes. Rhonda R. Shearer and Stephen J. Gould have already thoroughly documented these findings (1999), but even they highlight Duchamp’s insistence about the truthfulness of the note when directly and explicitly asked about this subject. In the following paragraph I present some considerations on this topic.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Tu m’, 1918

A simple measurement shows that the distance (as a straight line) between the visible extremities of each Stoppage is constant. Indeed, in Tu m’(Fig. 2) (description in a successive paragraph) the Stoppages appear carefully coupled, end against end. However, it is absolutely improbable that three threads, when freely dropped, dispose themselves showing, three consecutive times, the same distance between their extremities. This seems to confirm once more the practical impossibility to obtain the result shown by Duchamp in Three Standard Stoppagesaccording to the instructions contained in the note of the Green Box.

However, if Duchamp claims obstinately that he followed that operative protocol, this insistence induces some reflections. His work is intentionally marked with misleading traps and ambiguities; however, Duchamp usually operates in such a manner that our own sense deceives us, not his words per se. His challenge to the observer is fair and correct–the traces are intentionally ambiguous, but they are upfront with the observer in their objectivity–and the cleverness and analytical thinking involved in the interpretation of them is left to the reader.

Interestingly, we note that in the Stoppages, Duchamp carefully masked the equality of the lengths (in straight lines) of the three threads and their wooden templates.

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp,

Miniature version of Three Standard Stoppages,

in Boîte-en-valise, 1941

So, let us observe Duchamp’s “traps” that occur when the work is vertically displayed (as the orientation of the text labels of each thread suggests). For this aim I shall consider the miniaturized reproduction of Three Standard Stoppages in the Boîte-en-valise(1941) (Fig. 3), where all the six components of the work (3 threads and 3 wooden templates) are surely disposed by Duchamp himself. But similar considerations can be done for all the different dispositions I know, including that at MoMA.

The labels, placed near the bottom side of the canvases, are carefully lined up to each other, whereas the threads are glued starting from different distances from the top, which prevents us from comparing at a glance the lengths and the lining up of the extremities of the threads. One may impute this displacement to the randomness of each drop of the threads. Remember, however, that Duchamp cut the canvas strips (where the threads are glued) after the drop, successively, several years later. Duchamp could pay the same attention that he paid to the alignment of the labels to the alignment of the starting points of the threads. He used deceiving techniques analogous to these thread alignments for the presentation of the three wood templates. First, the order of the presentation of the threads (T) is, to say, TA, TB, and TC, whereas the wooden templates (W) are presented in the order WC, WA, WB. Second, the templates are rotated by 180° relative to the corresponding threads, which once more makes the comparison at a glance difficult. Third, in order to overlap the template on the correspondent thread, we have to mentally reverse the wooden templates WC and WA, because their outline shows a mirror symmetry with respect to the correspondent threads TC and TA, which presents new difficulties if one is looking for constant landmarks in the vision. The resulting scheme follows.

|

Fili (F)

|

Sagome (S) |

|

FA

|

FB

|

FC

|

SC

|

SA

|

SB

|

|

rotazione

a 180° & ribaltamento

|

rotazione

a 180° & ribaltamento

|

rotazione

a 180°

|

Finally in two templates the starting point for the curvilinear outline is marked by a well-visible dent in the wood (and at the same distance from the upper side), whereas in the third one we observe once more a displacement (forward) for the starting point of the curvilinear outline. With this last template it seems that Duchamp wants to give us a little clue: in this case there isn’t a dent at the starting point of the curvilinear outline, a dissimilarity that we perceive immediately.

We do not know whether these displacements in the composition of the elements are fortuitous. (We know, however, that Duchamp was very scrupulous when planning his works.) If not, we can think that what is so carefully hidden must prove extremely important. In the contrary case, we can at least understand why, so far, scholars haven’t considered the objective datum I discuss here in relation to the new difficulties it introduces for accepting the operative protocol declared by Duchamp for the Stoppages.

Hence, however it turns out, the constant distance between the extremities of each thread seems to be a crucial point.

Now, if Duchamp really let the threads drop down, then there must be some device to hold the distance between the extremities during the drop in such a way that they remain constant. At this point, we can conjecture several different techniques of execution, consistent with three types of evidence: what we can see in the Stoppages, what is described in the Green Box note, and what Duchamp claimed in several interviews. A few possible examples follow.

The first hypothetical device may be a simple tutor, as in the sketch in Fig. 4 (below)– the tutor would drop together with the thread.

click images to enlarge

Fig 4

Stoppages Device 1

The surplus of thread relative to the regular length of one meter, visible at the extremities of the device, would make up the stretches necessary for the tacking that we observe on the back side of the canvases. (They could already have the needle necessary for the tacking inserted.)

Two vertical slide bars could form another device, depicted in Fig. 5 (below). Like the first example, in this case, we could have a thread surplus for the tacking at the opposite extremities of the thread.

click images to enlarge

Fig 5

Stoppages Device 2

Although we must look at these devices as pure conjecture, we can at least acknowledge that in both cases, during the drop they would permit the thread to twist as it pleases, to keep that smooth linearity that seems impossible to obtain by dropping the thread freely, and to hold the distance between the extremities constant. Furthermore, (save for some mischievous reticence) the procedure described in the Green Box would turn out truthful and disprove notions that Duchamp was dishonest during the interviews.

However it turns out, by looking at Three Standard Stoppages we can consider two fixed points A and B, and three lines running through them, as showed in (Fig. 6).

click images to enlarge

Fig 6

Axiom of three

lines running through

two fixed points

This can evoke in our mind the Euclidean axiom of existence and unicity of the straight line through two points. It is well known that the Stoppages’ motif often reappears in Duchamp’s other works and acts as a basis for the development of further important conceptual ideas. We can consider that it is not arbitrary to think of this work as a sort of axiom, starting from which Duchamp deduces the construction of the whole building of his work (not exclusively geometric). However, it is important to realize just what exactly this axiom exerts.

In his funny and seemingly naive manner, it appears that Duchamp wants to remove from the Euclidean axiom the assumption of the unicity of the straight line through two points: the straight lines would be infinite, all of them obtained randomly by dropping the thread, and the three Stoppages representative of all of them (after all, we must remember that often in Duchamp’s work, “3” stands for multiplicity or infinity.) Indeed, we have known for quite some time that Duchamp was very interested in non-Euclidean geometry. Henderson states that:

For Duchamp, the n-dimensional and non-Euclidean geometries were a stimulus to go beyond traditional oil painting and to explore the interrelationship of dimensions and reexamine the nature of three-dimensional perspective. Like Jarry before him, Duchamp also found something deliciously subversive about the new geometries and their challenge to so many long-standing ‘truths.’ (341)

In any case, Duchamp’s conceptual operation is less naive than it seems at a cursory glance. In geometry, concepts like point, straight line, plane and so on, aren’t defined: they areprimitive entities or concepts; they are indirectly defined by their given usage rules, which are axioms and theorems; in other words, in a given geometry, point, straight line, plane…etc. can be whatever behaves exactly according to the axioms and theorems of that geometry. For instance, in the famous Poincaré’s model of hyperbolic geometry, the plane is depicted by means of a circle, and the straight line is a particular circumference arc. There seems to be an awareness of this aspect in Duchamp’s Stoppages; after all we know that Duchamp loved reading geometry texts, and as Shearer points out in Marcel Duchamp’s Impossible Bed and Other ‘Not’ Readymade Objects… Duchamp knew some aspects of Poincaré’s thought in particular (26 – 62). However, what is interesting in the perspective of this article isn’t the possible non-Euclidean content of the Stoppages‘ axiom, but the removal of the assumption of unicity. With this axiom Duchamp seems to claim a new principle: the one of repetition, or more precisely, the principle of the iteration of the same procedure following scrupulously the same rule.

1b. Network of Stoppages

click to enlarge

Figure 7

Marcel Duchamp,

Network of Stoppages, 1914

click to enlarge

Figure 8

Marcel Duchamp,Young Man

and Girl in Spring, 1911

Figure 9

Young Man and Girl in

Spring (1911), rotated 90°

The Stoppages reappear in a new work executed in the same period: the Network of Stoppages (1914)(Fig. 7). The network is painted on the unfinished second version of the earlier Young Man and Girl in Spring (1911) (Fig. 8). First, we note that with respect to the original orientation of Young Man and Girl in Spring (Fig. 9), the background for the Network is rotated by 90°. Many scholars, including Gould and Shearer, have noted that for Duchamp the right-angled rotation has special meaning and importance; this rotation usually denotes a passage from an n-dimensional space to an n+1-dimensional space (because adding a new dimension requires a new Cartesian axis, perpendicular to all the other previous). In the present case we have the passage from the monodimensionality of the single Stoppage, to the bidimensionality of the Network. But generally for Duchamp a rotation by 90° highlights the presence of a qualitative leap. Let us try to understand what kind of leap we see in the Network.

The thesis I assert here is that with this work Duchamp intuitively further focuses a new concept that today we call recursion, a concept that was latently under elaboration for some years, as we shall see.

In fact, in the Network Duchamp uses the Stoppages recursively: we have three Stoppages repeated three times, and the sets of three are organized in a hierarchical manner expressed by means of a quite abstract tree graph which seems to underline a ramification. The same ramification is the formal unifying motif of the painting Young Man and Girl in Spring, although here the ramification has the specific meaning of doubling: indeed, the whole composition is based on a Y-shaped motif. According to La sposa messa a nudo in Marcel Duchamp, anche, we must trace this motif back to the alchemic symbolism, where Y stands for androgyny (Schwartz, 111). Both the Young Man and the Girl lift their open arms as in a Y; their bodies themselves have an unnatural oblique disposition which, when observed upside-down, shows once more the Y-shaped ramification. At the bottom of the composition we note two branching arcs while at the top we find the ramification of a tree. At the center of the composition we find a circular shape, inside of which we see a little human figure. The tree with its branching starts from this circular shape; hence, if we look at the figures of the Young Man and the Girl as an extension of the tree branches, they constitute the ramification of the small human figure at the center of the composition. (According to Schwarz, the branching arcs at the bottom are buttocks, the circular figure represents Mercury in the ampoule, and the ramification of the tree represents a phallus; finally, the path I described would be followed backward, as the desire of re-conjunction of the youths into the primordial androgyne unity).

Whatever interpretation one gives for the painting, it shows an objective datum: the one of a doubling cascade, at which I look as a formal antecedent of the recursive motif. Furthermore notice that the spherical shapes, suggested by the arcs at the bottom of the composition, are repeated, by both the ampoule and several flowered shrubs in the background; and, more interesting, inside the spherical shrubs we observe several pink spherical inflorescence (like in the hydrangea). Thus we have a new suggestion of recursion: spherical flowers, inside spherical inflorescence, inside spherical shrubs, among other spherical shapes. Here, in addition, we have a first evidence of that repetition on a lower scale (shrub, inflorescence, flower) we’ll discuss later.

The spherical motif is in turn connected with an ulterior important motif: the one of the circularity. Once again, by following the doubling cascade in the painting one notices that the two arcs at the bottom (like fountain jets) sustain the circle containing the small human figure, starting from which the branching tree grows; the branches fall down again, by means of the ramification of the human figures of the youths, which in turn lean their feet just on the starting arcs at the bottom of the composition. In other words, in the painting we can see a sort of convective motion which circularly returns to the starting point.

Hence, executing the Network of Stoppages on the (unfinished) replica of Young Man and Girl in Spring, Duchamp points out the formal antecedents of the work. We can underline the close continuity between the two works observing that the sole definitive detail of the replica is the bust of the girl with her lifted and opened arms: this human ramification is grafted on the ramification of the Network with perfect continuity. This (recursive) graft of a work into another work will be, even in the following years, a distinctive element in Duchamp’s activity.

Previously we said that for Duchamp the right-angled rotations are special signals, by means of which our attention is alerted. Let’s examine the possible meanings in this case.

click to enlarge

The Bride Stripped Bare by

The Bride Stripped Bare by

Her Bachelors, Even [a.k.a. The

Large Glass], 1915-23

The bending of the Girl’s bust and the position of her arms denote her standing position, which is clearly contradicted by the orientation of the painting; it is saying, in essence, that it is not the figurative element of the girl that is important, but the formal motif of the branching. So, in the passage from the Youths to the Network, Duchamp asks us to focus our attention on a conceptual aspect (the one of recursion), while the narrative element (the one of the psychical world of the youths and of the connected events) is openly confined to the background (but clearlynot removed): this passage to the abstraction is the first qualitative leap.

As for the second leap, we can see it in the passage from a base 2 iteration (the doubling) to a base 3 recursion (three times three Stoppages). We have already underlined that often for Duchamp “3” means multiplicity or infinity.

I cannot conquer the temptation of advancing some interpretative conjectures: perhaps we are observing the lying Bride subjected to the tentacular embrace of the Bachelor, with arms lifted in the pleasure of the senses. Perhaps the Network doesn’t represent tentacles but flames: flames of desire or punishment. Perhaps we are witnesses of Duchamp’s progressive focusing of that man-machine graft that we shall see fully represented in the Large Glass(Fig. 10).

click to enlarge

Figure 11

Marcel Duchamp,

Nine Malic Moulds, 1914-15

However it turns out, the next station in the odyssey of Stoppages is marked by a new right-angled rotation, by means of which theStoppages‘ Network is prospectively projected into a horizontal plane, becoming the Capillaries’ system in the Bachelor Apparatus of the Large Glass. We need not stress the qualitative leap connected with this new rotation. It also implies (among other important considerations) the exportation of the principle of the number “3” (and of the number “9”) to the Large Glass, starting from the Malic Moulds (Fig. 11), which must be one for each Capillary, hence they must be just nine. (whereas we know from the reading of the Green Box notes that in the initial project they were only eight.)

1c. Tu m’

In 1918 Duchamp produced his last painting Tu m’, where he resumes and further elaborates the themes he developed in the meantime in the Large Glass. Inside the painting (which Schwarz, 1974, gives a complete and convincing interpretation) the Stoppages reappear in a new and strange composition, which I shall analyze in this section.

At the bottom left corner of the composition, we have a representation of the Stoppages‘ templates; here it seems that Duchamp wants to play fair: the templates are carefully lined up, in such a manner as to stress their equal length. The Stoppages are directly represented elsewhere in the painting, as we shall see below. However, Duchamp uses only two of the three templates, the first and the last; the central one, not used here, is the same that deceived us in Three Standard Stoppages (perhaps an expiation).

A hand painted roughly in the middle of the composition points clearly to the right side, where, at a glance, we immediately recognize the Stoppages; they are newly coupled, and form four pairs: the red Stoppage (corresponding to the lower template) and the black one (upper template). Interestingly, for the two upper pairs (a pair of pairs) the Stoppages have the same orientation, while in the lower pairs (another pair of pairs) the Stoppages have different orientations. Thus, we have a pair of pairs of pairs: a new hint of recursion, even though it returns to base 2.

Remember that we already observed the same oscillation between 2 and 3 as the numerical base for the recursion in the notes of the Green Box, where Duchamp projected only 8 (= 23) Malic Moulds (from which 3 Capillaries for each Mould should depart), while the definitive choice will be 9 (= 32, one for each Capillary). But this choice is not definitive, as is testified by the return to the 2 in Tu m’.

Let’s return to the description of the painting. The Stoppages seem to be freely soaring on the surface of the painting. Some colored rays, irradiating several circumferences, depart perpendicularly from the Stoppages (painted à la Kandinsky, suggests Schwarz). The rays prospectively suggest the dimension of the depth, and they seem vague allusions to evolutes and involutes of a curve that Duchamp could have read in geometry texts. Or, following Henderson the rays with their irradiation could be an allusion to the presence of electricity. In The King and the Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes (1912) and the Invisible World of Electron she says that

“Similar circular or spiraling imagery would continue to serve Duchamp in several subsequent works as an indicator of the presence of electricity or electromagnetism.”

Considering the depth suggested by the colored rays, our attention is attracted by a strange, skewed, milk-colored quadrilateral, slightly perceptible relative to the background with almost the same color. Thus, we notice that the four pairs of Stoppages start exactly from the four vertexes of the quadrilateral, perpendicular to it, forming a strange prism in perspective. The fact that theStoppages and the quadrilateral must be considered as a unique object is prospectively stressed by the shared vanishing point, placed on the lower side of the painting, on the right of the pointing hand. Hence, Duchamp attracts our attention to the strange prism (see Fig. 13).

click images to enlarge

Figure 13

A prism in perspective with

shared vanishing point,

Tu m’ (1918), detail

There is an interesting ambiguity (most likely intentional) in the choice of the representational system of this strange prism. We already observed its perspective frame with its vanishing point. Now, according to the rules of perspective, the farthest Stoppages would be perspectively shortened, but the Stoppages axiom imposes the rigid conservation of the lengths. All of this implies an axonometric (and not perspective) vision. As a consequence, Duchamp doesn’t draw (he can’t do it) the second face of the prism (parallel to the milk-colored first one), because this face would determine a second vanishing point, as showed in Fig. 14.

click images to enlarge

Figure 14

Second vanishing

point of the prism,

Tu m’ (1918), detail

Hence, the prism is simultaneously depicted by means of both a perspective and axonometric representational system. It therefore delimits an ambiguous space that, furthermore, seems to be closed but is really open. On the other hand, the Stoppages being generalizations of segments and straight lines, it was to be expected that the space delimited by the prism had some generalized properties relative to an ordinary space. But the discovery of the major extraordinary property of this region of the space is due to the fine observation capacity of Gi Lonardini, my wife. To understand it, we must turn our attention to the readymade shadows painted in the composition.

Starting from the left of the painting, we first have the shadow of the Bicycle wheel (1913) (Fig. 15) (following Schwarz’s interpretation, it would stand for Duchamp). Moving along to the right we observe the shadow of the Corkscrew (1918) (Fig. 16) (according to Schwarz, it would be the phallus of the Bachelor-Duchamp, which desires to consummate the incest with the Bride, and this would be the meaning of the tear in trompe l’oeil at the center of the painting). Finally, at the right, the shadow of the Hat Rack (1917) (Fig. 17) hung from the ceiling, symbolizes the hanging as punishment for the incest (again according to Schwarz).

click images to enlarge

-

Figure 15

-

Figure 16

-

Figure 17

-

The shadow of Bicycle Wheel

(1913) in Tu m’

(1918), detail

-

The shadow of Corkscrew

(1918) in

Tu m’ (1918),detail

-

The shadow of Hat Rack

(1917) in Tu m’ (1918), detail

|

What may elude us is the fact that, in the painting, a fourth shadow is (almost) ever present, the true one (i.e. not painted) projected by a true bottlebrush planted in the center of the tear, perpendicularly to the canvas; and with this fourth, even the 3 shadows would be recursively brought again to 4 (= 22).

I felt uneasy observing that the shadow of the Hat Rack seems awkwardly executed with respect to the other shadows whose execution is instead impeccable. Then I noticed that, while in the photos of the readymade the Hat Rack shows six stems, in the projected shadow one seems to see (although with some uncertainty) more than six stems: one, well marked, showing its typical curl, and others, blurred and only slightly suggested… Gi’s interpretation is that we are observing the shadow of a shadow. This is the extraordinary (recursive) property of the generalized space enclosed by the prism.

click to enlarge

Figure 18

Marcel Duchamp,Pencil-ink miniature of

Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2,

1918

A biographical event of Duchamp’s seems to be in relation with what we observed, and it seems to indicate a persistent presence of the themes, here discussed, in Duchamp’s thoughts that year. Reading Gough-Cooper and Caumont’s Effemeridi, I learned that on July 23rd, 1918, Duchamp gave his friend Carrie Stettheimer, for her doll-house, a pencil-ink miniature (9.5×5.5 mm) of his Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2 (1912) (Fig. 18), that was collocated in the miniaturized dance room. So, we observe the same idea of repetition in a box that we encountered in Tu m’, but here we have the further important specification of the reduced scale.

click to enlarge

Figure 19

Marcel Duchamp,

The Delights of Kermoune, 1958

We can recognize traces of the same idea of repetition in boxes and on a reduced scale in other works too. Recall, for example, The Delights of Kermoune (1958) (Fig. 19): Duchamp created a tree-graph that recalls the Network of Stoppages, composed by pine needles fixed on a sheet of paper with the same tacking technique used for the Stoppages; it was a “thank you” present for the hospitality received in Kermoune by Claude and Bertrande Blanc pain. Duchamp put this work in a gray box hidden in the wardrobe of the hosts.

In the idea of repetition in a box and on a reduced scale we may read a sort of foreboding of the fractal idea. A note in the Green Box states:

Make a mirrored wardrobe.

Make this mirrored wardrobe for the silvering.

|

Thus, if Blancpain’s wardrobe had been such a mirror wardrobe (with inner mirrors), then the little gray box would have been infinitely repeated, just as in a fractal.

click to enlarge

Figure 20

Marcel Duchamp,

Boîte-Series F, 1966

click to enlarge

Figure 21

Marcel Duchamp,

Reproduction of Why Not Sneeze

Rrose Sélavy(1920)for the Boîte, 1940

The theme of the repetition on a reduced scale is also widely developed in the Box in a Valise(1941) (Fig. 20). Here we notice another evocative resumption of the strange prism first observed in Tu m’: let’s look at the little model of the readymade Why Not Sneeze Rrose Sélavy?(1919), contained in the Box in a Valise (Fig. 21). The articleMarcel Duchamp: A Readymade Case for Collecting Objects of Our Cultural Heritage Along with Works of Art underlines an important property of the work: the starting point is a photo (2D) of the famous readymade, the little bird cage is cut along the right, upper and left sides, and this outline is then folded upon a skewed, solid prism (3D) which has the section similar to the one of the prism of Tu m’. Thus, we have a 2D surface, which simulates a 3D object (by means of the fold along the upper side of the front of the cage, so that it can overlap to the correspondent side of the prism). So, the dimensionality of this new object is a number between the integers 2 and 3.

click to enlarge

Figure 22

Marcel Duchamp,

Mina’s Poems à 2 Dimensions ½, 1959

Figure 23

Photograph of Katherine Dreier’s

library room before the installation of Tu

m’, 1918

There is a surprising coincidence: the idea of repetition (of the shadow, in Tu m’, and of the object on a reduced scale in the Box in a Valise) is openly associated with a non-integer dimensionality, i. e. with a fractal dimensionality: another evocative property of the strange prism. Elsewhere, we find Duchamp’s direct mention of a non-integer dimension in the verses composed for Mina Loy–the title is Mina’s Poems à 2 Dimensions ½ (Effemeridi, April, 14th, 1959) (Fig. 22).

A clarification is now necessary, to avoid possible misinterpretations. I don’t want to state either that the examined works (and others that we shall examine below) are fractals (fractals are well defined geometric objects, with several well defined properties which we can’t observe in Duchamp’s work: this is absolutely obvious), or that Duchamp explicitly grasped such a concept. We must only acknowledge that the idea of recursive repetition on a reduced scale is objectively related to that of fractals, so that, in the presence of the idea of recursion (even though only suggested) the idea of the fractal must also take some evidence, at least in an embryonic form. I think (and I began to show elsewhere, Giunti, 2001b) that, to the extent that the intuition of recursion will become more and more definite and precise by artists, the representation of fractals will become conscious and more and more clear and pertinent (as in the cases of Klee and Escher). However, we must recognize that the intuition of a non-integer dimensionality, especially when related to the repetition on a lower scale, is an extraordinary intuition that we can’t observe in any other artist of the same period, as far as I know. Remember also that Mandelbrot’s first book on fractals, Les objets fractals gives the mathematical definition of fractals in terms of non-integer dimensionality and was issued in 1975. Finally, we return to Tu m’ for a last consideration. A photo I have seen in the Effemeridi (January 9th, 1918) shows Miss Dreier’s library room before the installation of Tu m’ (Fig. 23). In the foreground we clearly see a birdcage. Maybe the strange prism was originally conceived just as a cage.

1d. Two Brief Circular Digressions

click to enlarge

Figure 24

Figure 25

Marcel Duchamp, Sad Young

Man on a Train, 1911

Marcel Duchamp, Family

Portrait (1899), 1964

Although the recursion theme is frequently linked to the Network‘s motif (we shall see in the next section another important example referred to as the Odyssey of Stoppages) we recognize its echo in other works along the whole artistic career of Duchamp. Here I want to discuss two further works, both referable to his biography; these works are emblematically placed at the opposite extremities of his artistic life: Sad Young Man on a Train (1911) (Fig. 24) and Family Portrait (1964) (Fig. 25). Sad Young Man on a Train is a self-portrait (where Duchamp represents two loved objects: the pipe and the walking stick). Let’s read Duchamp’s description:

“First, there’s the idea of the movement of the train, and then that of the sad young man who is in the corridor and who is moving about; thus there are two parallel movements corresponding to each other.”

The idea of a movement inside a movement is certainly recursive, and it is underlined by the alliteration of the original French title of the painting: Jeune homme triste dans un train. This alliteration (triste, train) is analyzed in an important article by Gould (2000)recalled extensively in the next section of this paper. Among other considerations, Gould wondered why the young man must be sad at all. He hypothesizes several answers. Here I shall resume two of them.

The first cause of sadness is that the young man feels that his own motion adds only a scarce contribution to the overall motion of the train. This conjecture in turn leads me to a further conjecture. If we look at the motion inside the motion as an early intuition of a fractal idea, then the sadness of the young man would be related to the intuition of an important feature of fractals: the dimensional scaling. Thus, the sadness of the Young Man is similar to the one of Achilles, in Zeno’s paradox, for his impossibility to reach the Turtle.

The second cause of sadness is that in his motion the young man is twice bound (by both the binary and the corridor) to a linear pathway, which Duchamp feels is strongly limiting, so there seems to be the perception of the narrowness of the linearity; in fact, in the same year Duchamp introduced the important element of the circularity in the iterations for his workYoung Man and Girl in Spring by means of the convective turbulence which we observed in a previous paragraph.

click to enlarge

Figure 26

Duchamp’s family photo,

1899

Figure 27

Salvador Dalì, Slave Market with

Invisible Apparition of Voltaire’s Bust,

1940

Let’s now consider Family portrait, where we see the child Marcel together with his parents and little sisters. It is an old family photo (1899) (Fig. 26), which Duchamp cut along a strange curvilinear outline. We recognize an Arcimboldo-like technique, widely experimented also by Salvador Dalì (see for instance the famous Slave market with invisible apparition of Voltaire’s bust (Fig. 27) or, even better, The Face of the War, both 1940): we see a human bust composed of several little human busts–recursion everywhere (and something which again recalls fractals). The mother’s and Magdeleines’ heads form the eyes, while Marcel’s head is the mouth. Finally, Suzanne, Yvonne and the father Eugene form the arms and the thorax. Let’s avoid for now the discussion about the meaning (not only psychological) of the exclusion of Marcel’s brothers from this composition (we shall recall this important topic in a successive paragraph, because it requires the acquisition of new elements). Instead, let us confine ourselves to the formal consequences of this exclusion: we notice that the shape formed by the exclusion of a brother functionally constitutes the armpit’s socket in the overall bust of busts, while the permanence of the second brother and of the other people present in the original photo would hamper the perception of the overall outline of the bust.

Notice now that Duchamp obtained this readymade starting from a family photo (his own family). Thus, the recursion we noticed on the formal level is related on the content level to the cyclical recursion of the generation replacement, in which the sons become the new parents, who will have new sons, who will become new parents… Hence, we have the association between cyclicity and recursion; it is reinforced because the outline of the cutting no longer shows the rectilinear rigidity of the early self-portrait, but instead the smooth curves and roundness which Clair (2000) relates to those of a famous readymade: the Fountain (1917). A more detailed discussion about Clair’s observation follows in subsequent paragraphs.

Finally, if we look at the Family Portrait as Duchamp’s phylogeny, then we could look at the early self-portrait of Sad Young Man on a Train as his ontogeny (after all this self-portrait isn’t static, but instead a rather dynamic representation of his own temporal evolution). If so, we would recognize the implicit statement that both processes share the same recursive modalities.

2. Rrose’s Language

2a. The Language note in the Green Box

We read, in the Green Box, two notes stating the following:

Conditions of a language:The search for “prime words“(“divisible,, only by themselves and by unity) and

Take a Larousse dictionary and copy all the so-called “abstract”words, i. e. those which have no concrete reference. Compose a schematic sign to designating each of these words (this sign can be composed with the standard stops) These signs must be thought of as the letters of the new alphabet. A grouping of several signs will determine

(utilize colors-in order to differentiate what would correspond in this [literature] to the substantive, verb, adverb declensions, conjugations etc.)

Necessity for ideal continuity. i.e.: each grouping will be connected with the other groupings by a strict meaning (a sort of grammar, no longer requiring pedagogical a sentence construction. But, apart from the differences of languages, and the “figures of speech”peculiar to each language-; weights and measures some abstractions of substantive, of negatives, of relations of subject to verb etc, by means of standard-signs. (representing these new relations: conjugations, declensions, plural and singular, adjectivation inexpressible by the concrete alphabetic forms of languages living now and to come.) This alphabet very probably is only suitable for the description of this picture.

In this note Duchamp hypothesizes about the creation of an artificial language, which must be a generalization of the natural languages. The logic underlying the construction of the new language has two essential and deeply linked aspects: recursion and abstraction.

Regarding the first aspect, the one of recursion, notice that the atomic elements of the new artificial language, i.e. the phonemes, are certain words, taken from a dictionary of a natural language, which Duchamp indicates as prime words (my hypothesis about the meaning ofprime words follows in the next paragraph). Therefore, the phonemes of the new languages are words (combination of phonemes) of a natural language: phonemes of phonemes, words of words. A new graphical sign, i.e. a grapheme, composed by means of the “standard-signs” that I think to be (at least related to) the Stoppages (hence a grapheme composed by graphemes) corresponds to each new phoneme of the artificial language. Hence, by synthesis, Duchamp designs an artificial language, which in turn is a recursive generalization of a natural language.

The second aspect, the one of abstraction, can be referred to the focus on the syntax of the new language; indeed Duchamp talks about ideal continuity, strict meaning, weighs and measures some abstractions of substantives, of negatives, of relations … whereas the semantics is clearly devalued, when he talks about the absence of pedagogical a sentence construction, and the “figures of speech”peculiar to each language …

Looking at the application of the recursive method and at the vocation to generalizing abstraction, it is possible to see a sort of intuition of two aspects that really characterized the linguistic research in the second half of the 900’s.

Starting from the first aspect, we know that in the so called generative grammars the phrase is constructed by means of recursive grammatical rules, where each symbol can be rewritten (i.e. substituted) by other symbols, which in turn can recursively contain the rewritten symbol itself (see for more information Ghezzi and Mandrioli, 1989, or the classic Grishman, 1986).

The production of a sentence by means of such a grammar is often depicted in a special tree-graph in which each rewriting corresponds to a new ramification. The following simple example is taken from the classic Chomsky’s Universal Grammar. An introduction. The starting symbol is S (as Sentence); the other symbols are: NS (Nominal Syntagm), VS (Verbal Syntagm), D (Determinant), N (Noun), V (Verb); the grammatical rules are:

|

S -> NS VS

NS ->D N

VS ->V NS

(the symbol -> stands for “rewrite with”).

|

This grammar produces simple sentences in the form Subject-Predicate-Object, as in: “The child drew an elephant” (Cook). The corresponding tree-graph is depicted in Fig. 28.

click images to enlarge

Fig. 28

Interestingly, we notice that the sole grapheme produced by Duchamp by means of theStoppages is a tree-graph: the one of Network of Stoppages.

As for the second aspect, it is well known that the project of a universal grammar is nothing else than an effort to individuate, by means of progressive generalizations, those grammatical abstract structures shared by all the natural languages. Maturana (1978) precisely points out the importance of the recursion as the universal founding element of each language:

Conversely, the ‘universal grammar’ of which linguists speak as the necessary set of underlying rules common to all human natural languages can refer only to the universality of the process of recursive structural coupling that takes place in humans through the recursive application of the components of a consensual domain without the consensual domain (52).

Coming back to Duchamp, the note on the language ends with an important consideration: what is this new artificial language for? Duchamp answers explicitly: it’s for describing this picture, i.e. the Large Glass (recall that the notes in the Green Box refer to the design and to the description of the Large Glass). Why is it so? Because this language shares with theLarge Glass the nature of progressive and recursive generalization. But, if this language serves for the description of the Large Glass, then it also serves for the writing of the Green Box notes (which are parts of the Large Glass), among which it is just the note itself that describes the language. (Here, we have a first example of those self-referential cycles typical of Duchamp that we shall discuss below.) Indeed we notice that in the Green Box notes Duchamp really uses a strange and stretched syntax, that does not agree with the usual syntactical rules of the natural languages– we have transitive verbs without objects, hypothetical periods without conclusions, unsolved parentheses, and so on. Thus, the language of the Green Box is perhaps a first approximation of the new language, “representing these new relations: conjugations, declensions, plural and singular, adjectivation inexpressible by the concrete alphabetic forms of languages living now and to come.“

2b. Prime Words and Self-Production

Now, we shall try to clarify the meaning of the prime words. Following the suggestion of Calvesi, I think that they are primary vocal emissions, like the word “Dada,” or like the first syllabic articulations of a child, like “mama”or “papa,” when they haven’t yet a precise semantic reference (to abstract words, says Duchamp), i.e. when they are still only pure combinations of elementary phonemes (135). So I look at the prime word and the abstract word as synonyms.

Thus, we can see some first examples of this new language, I think, in Duchamp’s nonsensical wordplays based on cascade alliterations. The most famous being:

Esquivons les ecchymoses des Esquimaux aux mots exquis.

Gould analyzed this in the above-mentioned essay (which for me has been a source of both inspiration and pleasure). It is a question of rearrangement of some principal syllabic groups, that in this context we can consider as phonemes. The fact that from this combination of syllables into words a non-sense arises corresponds exactly to the programmatic devaluation of the semantic aspect relative to the syntactic one. Here syllables have a value exclusively because of their combinatory grammar, but they haven’t any overall semantic reference; there isn’t any pedagogical a sentence construction, any figures of speech (read, as I believe: idiomatic form). The grammatical rules for the syllabic rearrangement are abridged in the following simple (recursive) grammar that can generate Duchamp’s wordplay (and infinitely other non-senses, with the same structure, in a pure French grammelot):

The starting symbol is P.

The other following symbols (in capital letters) are the so-called non-terminal symbols (i.e. the symbols which must be rewritten): W (Word), C (Connective), D (Double syllable), S (Simple syllable), E (syllable starting with E), K (Key syllables). Finally, the following (in lower case) are the terminal symbols (i.e. the symbols which cannot be rewritten): es, ek, ex, von, mos, mò, mot, key, keys; they transliterate the pronunciation of the corresponding French syllables.

The symbol | stands for “or”.

P -> W C W

C -> C W C | les | des | o (notice that this rule is recursive)

W -> D S | S D

D -> E K

E -> es | ek | ex

S -> von | mos | mò | mot

K -> key | keys

Fig. 29 shows the derivation of the “Duchampian”wordplay.

click to enlarge

Figure 30

Marcel Duchamp,

Rotary Demisphere, 1925

Gould correctly underlines that the above analyzed wordplay is written by Duchamp on the Rotary Demisphere (1925) (Fig. 30), an optical device which, when rotating, produces the appearance of an outwardly cascading spiral. This meaningful association is very important because it shows that, in Duchamp’s intentions, in this play there is a potentially unfinished self-production. Using the grammar proposed above, it is easy to verify this property, if one accepts not only non-sense sentences, but also non-sense words. (Remember that the present grammar generates sentences in a pure French grammelot.)

2c. Self-Reference and Self-Production of Sense

Duchamp’s wordplays often have another important characteristic: the self-reference. As a first example let’s consider the following:

Si la scie scie la scie

et si la scie qui scie la scie

est la scie qui scie la scie

il y a suissscide metallique.

[If the saw saws the saw

and if the saw sawing the saw

is the saw sawing the saw

then we have metallic sew-cide]

The Effemeridi (March 17th, 1960) states that the passage was composed for an artwork by Jean Tinguely (a happening, we could say) in whose scene an army of saws was originally planned.

The wordplay isn’t memorable, but it is particularly useful to introduce what is interesting here, because the image of the saw that saws itself is clearly self-referential. Furthermore, there is the above-discussed element of the proliferation by means of the syllabic repetition (self-construction). Finally, we have at least an amusing suiss-scide, with nearly identical sound of suicide, i.e. a suicide of Swiss (suiss) saws (scie – scide), that Duchamp wrote maybe thinking to the army of saws that move themselves with perfect synchronism (with Swiss precision) until the unaware, dull suicide (self-destruction).

Curiously, Tinguely’s happening had unexpectedly the same characteristics of the wordplay: it was self-destructive (and this was expected) but also self-constructive (and this was unexpected). Fanciful machinery, made with each sort of recycled material, had to destroy itself with a fire. At a certain moment, fearing for the possible explosion of an extinguisher because of a sudden breakdown, Tinguely begged for the intervention of the fireman, who, instead, hesitated; when finally the fireman started with his operations, he risked lynching, because the spectators considered his intervention inopportune in the happening context. So, in the interaction of the work and its spectators, an unexpected and quite comic event happened to self-generate.

Let’s now return, after this digression, to the self-reference theme in Duchamp’s wordplay. He pursues this target with subtle and effective techniques. As examples I shall consider two wordplays, recalling Gould’s analysis and developing some further considerations. The first wordplay, is quite simple:

Cessez le chant

laissez ce chant

[stop the song

leave this song]

Gould observed that swapping the initial consonants (C and L) between the first two words of each line, according to the scheme:

C L

L C

provokes a pleasant auditory chiasmus and, at the semantic level, an inversion in the sense of the sentence. Here I want to underline that each of the two text lines, taken for itself, hasn’t any particular value beyond its obvious semantic reference; but a new sense is created by the conjunction of the two sentences because of their internal reciprocal references: that of the auditory chiasmus and that of the sense inversion. In other words, the conjunction produces an added value that goes beyond the pure sum of the semantic value of the sentences. Hence, in the wordplay the whole is superior to the sum of the parts, and the added value is generated because of the internal cross-reference, i.e. this wordplay is self-referential.

The second wordplay, more complex and fascinating, is bilingual (French vs. Latin):

éffacer FAC

assez AC

[erase DO

enough AND]

The word éffacer sounds like a contraction of ef (F) and éffacer (erase); hence it’s meaning is somewhat like: erase the F. Now, putting into effect the command on the same wordéffacer (hence a self-referential operation), we obtain acer, whose homophone is assez, i.e. the second French word. Here all would stop, because assez means enough, as if to say: that’s enough–all is finished. Here the Latin part comes into play. Applying the same F-deletion to the first Latin word, we pass from FAC (do) to AC (and). The writing is so completed. Notice that each Latin word has a semantic value opposite to the one of the correspondent French word, so that it creates an alternation of orders and countermands, underlined by the language passage. Now we can see the most interesting part–the last word AC (and) implicitly suggests the addition of something. If this thing would be just the previously omitted F, and if we would put into effect the command (like the operations in the passage from the first to the second line) we would obtain efassez FAC, homophone oféffacer FAC. So, we would have a cyclic return to the starting point, in an infinite periodic motion.

In the latter wordplay we can see, with stronger evidence than in the former one, an intrinsic self-reference: the four words, if taken one by one, have a scarce meaning (just their direct semantic reference); but the self-established relations between those words creates an engine that produces new sense. More precisely, the first among the four words contains in itself the germ of the entire machinery, and in the internal relations with the other parts of the system it self-generates a potentially infinite circular motion. Once more, and with greater evidence, the self-reference generates new organization and then new sense.

It is evocative to think that a little jewel like the last wordplay can condense in itself a lot of features not only of several other works, but also of the whole of Duchamp’s work. Particularly, the typical Duchampian idea of re-contextualization of his previous works, as for the Stoppages, is intrinsically self-referential, because Duchamp always refers to a previous Duchamp. In the cyclic and recursive reuse without end of similar ideas in newer and newer contexts, there arise qualitative leaps, those generalizations, and added values or, as Bateson says, that hierarchy of logical types that make his work and his thought progress (155). Each single element of his inextinguishable mental activity contains in nuce, the essential germs of the overall features; each element of his production potentially contains a quantity of information sufficient to re-run through (if not to recreate) his whole production, exactly as in living organisms, where each cell contains the genetic information potentially able to regenerate the whole organism.

3. The World of the Wasp

Let’s consider another important note from the Green Box.

Top Inscription.

obtained with the

draft pistons.

(indicate the way

to “prepare” these pistons).

Then “place” them for

(2 to 3 months)

a certain time and let

them leave their

imprint as

3 nets through which

pass the commands

of the Pendu femelle (commands

having their alphabet and

terms governed by the

orientation of the 3 nets

[a sort of triple “cipher”

through which

the milky way supports

and guides

the said commands]

Next remove them

so that nothing remains

but their firm

imprint i.e. the

form permitting all

combinations of letters sent

across this said triple form,

commands, orders

authorizations, etc.

which must

join the shots

and the splash

This note contains a lot of suggestions, which so deeply resonate with my way of seeing things that it is very difficult for me to discern the projections of my imagination from what is really present in the note itself. However, due to the peculiar language used by Duchamp for the Green Box‘s notes, the analysis always gives free play to one’s imagination (intentionally, I think, by Duchamp).

Coming to the specific of the note, observe that the Bride’s orders pass through the nets: in the Large Glass system the Bride is queen. One of her essential apparatuses is the so-calledWasp, and the idea of a wasp-queen makes me think to the social organization of the Hymenoptera (insects like bees, ants or just wasps). At the vertex of their complex systemic organization there is the queen. In addition to the important reproductive function, she regulates many vital functions of the community by emitting some chemicals (for instance, when a certain concentration of a particular hormone produced by the queen is reached, then a new swarming is induced). In fact, from the viewpoint of an observer, these chemical emissions can be described as orders. The Milky Way at the top of the Large Glass really has the appearance of an entomological representation (like a large caterpillar, or like the flaccid abdomen swollen with eggs of the queen). An undeniable entomological suggestion also emanates from the description of the Wasp apparatus, with its secretions, thefilamentous material, the ventilation mechanism (just as in a hive). In brief, the first suggestion is for a representation of an insect society: at the top lies the queen, at the bottom there is the intricate industriousness of the subaltern castes.

Now, we must underline a little but meaningful detail. In the Large Glass the Wasp is only one of the Bride’s apparatuses, whereas I have spoken about it in terms of just the Bride. This identification between part (the Bride’s apparatus) and whole (the same Bride) is authorized by Duchamp himself, as we shall see better below, because it is the same relation, openly declared by Duchamp, between the Bride (part) and the Large Glass(whole): thus, the identification whole-part (Glass-Bride) is repeated (once again) on a lower scale (Bride-Wasp). Furthermore the identification Bride-Wasp is consistent with the Bride’s psychic portrait made by Schwarz (1974). Schwarz also recalls a nightmare which Duchamp had while he was terminating the Bride in Munich: the Bride became an enormous insect that atrociously tortured him (147).

click to enlarge

Figure 31

Marcel Duchamp,

A Guest + A Host = A Ghost, 1953

(A little digression. These entomological considerations would give a new meaning to the Duchampian wordplay: A Guest + A Host = A Ghost (Fig. 31), already widely analyzed by Gould. Several wasp species lay the eggs on a previously paralyzed caterpillar, or even inside it; thus, at the hatch, the wasp grubs will feed with fresh flesh, having the precaution to eat starting from the non-vital organs of the caterpillar. Talking about the parasitism, the parasited organism, here the caterpillar, is the said Host; if we indicate the wasp grub with the word Guest, then the word Ghost will perfectly depict the fate of the poor Host).

The second suggestion refers to the punched cards of either the industrial machines or certain musical barrel organs which one could see along the streets of a city in those years. Punched cards means coded orders; hence, the queen issues her orders disposing particular combinations of the holes of the three nets–punched cards.

The three nets are placed in loco for as long as two or three months, so that they can spontaneously and plastically assume a shape that conforms to the flow of the Bride’s orders; thus, the code useful to transmit the Bride’s orders will automatically organize itself–it will be based on the system of the mutual positions of the three nets. This code will then remain permanently impressed in the system by means of their trace.

Thus, Duchamp provides for a prolonged exposition of the nets to stochastic events, which will model their own code. Biologically speaking, all of this evokes the idea of an adaptive process in progress. Exactly like the one that produced evolution of the effective biochemical system for the self-regulation of a hive. My last suggestion from the note, closely linked to the previous one, is mathematical, and refers to the behavior of the neural networks. Gurney states his definition :

A neural network is an interconnected assembly of simple processing elements, units or nodes, whose functionality is loosely based on the animal neuron. The processing ability of the network is stored in the inter-unit connection strengths, or weights, obtained by a process of adaptation to, or learning from, a set of training patterns.

In other words, the neural networks are mathematical formalisms, which simulate the interconnections and the activity of the neurons. They are formed by numerical variables, interconnected in a network-like structure and recursively recalculated, in such a manner as to optimize the performances of the network itself, on the basis of the target for which it is designed, proceeding by trial and error.

Hence, the neural networks model themselves by a process sometime very similar to the evolutionary one, on the basis of the target, which is pursued as a goal from time to time. Thus, the neural network exhibits the same kind of organization as the evolutionary process. This is the way the networks learn: it is a process of internal and recursive self-organization.

Undoubtedly, all this is very similar to the behavior imagined by Duchamp for his Milky Way nets.

It is now necessary to underline that in the years when Duchamp wrote the Green Box notes neither biochemistry (especially when applied to the study of hive behavior) nor the neural networks (especially the so called multi-layer network as is the case with Duchamp’s networks) existed. Thus, I don’t want to hypothesize either that Duchamp was influenced by the knowledge of similar concepts, or that he wished to create with the Large Glass a metaphor of a complex system (like an insect society or a neural network). Finally, I don’t want to state that Duchamp’s intuitions forerun in any way some future specific scientific result.

Simply, I think that concepts like recursion, self-reference, circular feedback (and so on) are so deeply linked to each other and to the concept of self-organization that the latter aspect must somehow find an expression, even if implicitly, as in the present case.

click to enlarge

Figure 32

Photograph of Duchamp’sDust

Breedingby Man Ray, 1920

Further clarification is also necessary. Even in the elaboration of the Seives of the Large Glass, Duchamp planned another stochastic system (and really executed it), exposing the Glass to the dust throughout about four months. The famous photo of the detail of the Large Glass covered by dust, executed in 1920 by Man Ray, titled Dust Breeding (Fig. 32), documents the result. However, this example (although important) doesn’t concern the above suggested aspect of self-organization. Here we have a pure randomness that blindly produces a result, surely interesting, but without a specific organization; there we had the same randomness, which instead produced organization (the creation of the code). In other words, and speaking in terms of entropy: here we have an increasing entropy, where previously we had a reduction.

Marcel’s Topology

4a. Recipe for Bottles

We read, in the Green Box, the note:

…on the other hand:

the vertical axis considered separately turning on

itself, a generating line at a right

angle will always determine

a circle in the 2 cases 1st turning

in the direction A, 2nd direction B-

Thus, if it were still

possible; in the case of the vertical axis at

rest., to consider 2 (contrary) directionsfor

the generating line, the figure engendered

(whatever it may be.)

can no longer be called left

or right of the axis-

-As there is gradually less differentiation

from axis to axis., i.e. as all the

axes gradually disappear

in a fading verticality the front and the back,

the reverse and the obverse acquire a

circular significance: the right and

the left which are the 4 arms of the front and

back. Melt. Along the verticals.

———

The interior and exterior (in a fourth dimension)

can receive a similar identification. But

the axis is no longer vertical and has no longer

a one-dimensional appearance

Although the note is a little bit obscure, and as always it’s reading is arduous, it is possible to hypothesize an interpretative model consistent with its principal parts; furthermore, this model is consistent with some of Duchamp’s capital works.

Let’s start by imagining a simple rectangle. If we trace a vertical axis across this rectangle, it makes sense to distinguish right and left parts of the figure with respect to that axis. Now, if we are in a 3D space, with a circular motion we close the rectangle to form a cylinder (Fig. 33A).

click images to enlarge

Fig. 33A

It no longer makes sense to speak about right and left parts with respect to the previous axis, because each point of the cylinder can be reached by turning toward either the left or the right.

If we use the rectangle to represent the cylinder in a 2D space, we must agree upon the simple convention that the two vertical sides of the rectangle represent the same line of the cylinder. Thus, if we walked on the rectangle as if we were on the cylinder, when we went out from the left side we could continue re-entering from the right side, and vice versa, as shown in Fig. 33B and 33C.

click images to enlarge

click to enlarge

Figure 34

Marcel Duchamp,

Door: II, rue Larrey, 1927

Duchamp applies this idea to the suggestive Door: II, rue Larrey(1927) (Fig. 34): when the door closed the left room, it opened the right one, and vice versa.

Thus, by means of a simple circular closing we pass from the rectangle to the cylinder, losing the distinction between left and right. Now, if we repeat the same operation of circular closing starting from the cylinder, we obtain a ring-shaped figure which topologists call torus or tore (Fig. 35A). With this operation we lose the distinction between high and low too.

click images to enlarge

Fig. 35A

Fig. 35A

As before, if we use the rectangle to represent the torus in a 2D space, we must agree upon a second simple convention, analogous to the first one: the two horizontal sides of the rectangle represent the same circular line along the torus, and if we walked on the rectangle as if we were on the torus, when we went out from the top side we could continue re-entering from the bottom side, and vice versa, as shown in Figs. 35B and 35C.

click images to enlarge

And now the last step. Referring once again to the rectangle in the 2D space, let’s maintain the two rules for the entrance and the exit of the horizontal and vertical edges of the figure, and let’s introduce a minute but important alteration in the second one: when we go out from the top side we could re-enter from the bottom swapping left and right, and vice versa (Fig. 36B and 36C).

click images to enlarge

It is easy to show that when we pass from the cylinder to the torus we haven’t such a swapping between left and right. See in Fig. 35A the edges of torus before the closing: we go along the two circles walking with the same orientation (clockwise or anticlockwise in both the cases).

click images to enlarge

Fig. 35A

So, the torus doesn’t agree with the new swapping of the second rule. We only obtain the desired effect if the starting cylinder penetrates itself (with a self-intersection) before closing itself, as depicted in Fig. 36A

click images to enlarge

Fig. 36A

click to enlarge

Animation A1

The formation

of the Klein Bottle

Animation A2

The Klein Bottle

The new strange figure is called Klein Bottle (from the mathematician Klein). The Animation A1 helps us visualize the formation of the bottle starting from a simple rectangle, by means of two simultaneous circular closings. (En passant: we must admit that a kleinian surface would be a very good place to draw a suicide saw!)

This object has many strange topological properties, among which we cite the most important for the present context: while the torus has two faces (internal and external) the Klein bottle has only one face, because with this figure we lose the distinction between inner and outer, as we can easily verify with a little effort of imagination, in a mental exploration of the object. Animation A2 may serve to illustrate this aim. All this agrees with the note’s statement: “The interior and the exterior (in a fourth dimension) can receive a similar identification.” An interesting question arises: does Duchamp’s hint to the 4D space in this note have a correspondence with the well known fact that in a 4D space, we could realize a kleinian bottle without intersecting surfaces? Rosen presents the necessity of a fourth dimension for the building of a kleinian bottle without self-penetration clearly and intuitively in a non-technical manner with some important philosophical implication (1997). Finally, we can hypothesize a possible meaning for the enigmatic final statement about the axis, that is no longer vertical and has no longer a one-dimensional appearance–if we look at the axes as the lines along which we close the rectangle twice (the first time for the passage to the cylinder and the second time for the passage to the Klein Bottle) we no longer have one axis but two, so we no longer have unidimensionality.

click to enlarge

Animation A3

Moebius Band

Animation A4

Two Moebius

Bands forming a kleinian bottle

In the construction of a kleinian bottle I showed that in order to obtain the left-right swapping during the second conjunction, self-penetration is necessary. It is, however, possible to have a similar swapping by cutting a cylinder and re-closing the surface after a 180° torsion, as showed in Animation A3.

It originates a topological figure called Moebius band; this strange figure has a single face and a single edge. From the conjunction of two Moebius bands along their sole edges, we obtain a kleinian bottle, as Animation A4 may help visualize.

click to enlarge

Figure 37

Marcel Duchamp,

Sculpture for Traveling, 1918

In the realization of the Sculpture for Traveling (1918) (Fig. 37), Duchamp seems to use a technique, which quite nearly recalls some of the procedures previously described. It is well known that he glued to each other several irregular colored rubber strips, cut from bathing caps. The original object is lost, so we must refer to the historical photo and to the description that Duchamp himself did. With some difficulties, some self-penetration and some torsion can be possibly discerned in the historical photos; the description of the work made by Duchamp to Jean Crotti (Effemeridi, July 8th, 1918) talks about rubber strips “glued together, but not flat” (italics mine). I think he alluded to some torsion (as the one necessary for the Moebius band) before the gluing. From the same source we learn that Duchamp considered the Traveler’s Sculpture more interesting than the painting Tu m’.

4b. Bottle in Art in Bottle

click to enlarge

Figure 38

50 c.c. of Paris Air, 1918

Marcel

Figure 39

Marcel Duchamp,

Duchamp, Pulled at Four Pins, 1915

Jean

Clair (2000) argues that Duchamp surely knew the Klein Bottle and

its important topological properties; he also indicates in the previously

analized note a possible reference to it. In addition, he hypothesizes that

the ampoule of Paris Air (1919) (Fig.

38) could refer to it (both iconographically and

because of the problems it poses). This statement holds its validity for

others of Duchamp’s works as well.

The readymade, Pulled at Four Pins (1915) (Fig.

39), a simple chimney cowl, is another example. In the related

drawing, which Duchamp made in 1964, at the top of the shape we see a

curvature that recalls the glass curl of the ampoule, cited above; furthermore,

we must think that a chimney cowl serves to aid the convective circulation

of the air between inside and outside.

click to enlarge

Figure 40

Marcel Duchamp,

Fountain, 1917/1964

Let’s now consider the famous Fountain (1917) (Fig. 40). It seems to me that it can be seen as a transversal section of a kleinian bottle. The neck for the connection with the water pipe (in the foreground of the historic photo) would be the equivalent of the kleinian bottle neck–plunging in its own belly (here the sectioned part) would reconnect with the holes of the draining (corresponding to the introverted bottom of the kleinian bottle).

In fact the double function as a fountain (supplying device, oriented to the outside) and as a urinal (receiving device, oriented to the inside) seems to be the first confirmation of this reading.

Often the signature R. Mutt (or Mutt. R., or Mutt Er) is said to stand for Mother (Mutter in German). This adds a further meaning to the association between the Fountain and the kleinian bottle. Indeed, “Mother” is the one which potentially has in her belly her offspring; her belly, i.e. her inside, is everted

to the outside by means of her offspring, who in turn contain offspring

in inside, who soon will be everted, and so on. In the present of a woman

is contained her future; in this contemporaneity of present (inner) and

future (outer) that expresses itself in a sort of temporary evertion,

we can grasp an analogy with the properties of the kleinian bottle.

If we accept this viewpoint, then we can also understand this very cryptic note in the Box of 1914:

One only has: for female the public urinal and one lives by it.

These considerations cast in turn a new sense on the readymade Family Portrait. We have already recalled that Jean Clair looks at its outline as a template of the Fountain. This comparison is consistent with the observations above. In fact the Mother (with the last born) is at the top vertex of the composition. The exclusion of the male offspring underlines the continuity of the female line in the descent. The male is only a reproductive device: the father is indeed in a peripheral position. Why then is the presence of the young Marcel in a central position? The theory of Marcel’s drive for his sister could be a possible explanation, but I think that Marcel’s role is simply that of an observer.

Finally, I want to recall that the outline of the Fountain is sometimes regarded as a symbol of the Buddha. If this is so, and if we want to keep the kleinian analogy, one wouldn’t think of the image of the erect sitting Buddha, but instead of the one in which the Buddha is completely bent in on himself, plunged in that inward meditation that opens the door to the contemplation of the universe. In the above mentioned essay, Rosen

suggests that:

“the ‘fourth dimension’ needed to complete the formation of the Klein bottle engages the inner dimension of human being; it is not just another arena for reflection, one that stretches before us; rather, it is folded within us, entailing the prereflective depths of our subjectivity.”

click to enlarge

Figure 41

Marcel Duchamp,

Boîte-Series G, 1968

Duchamp often claims that three particular ready-mades synthesize the world of the Large Glass, and in the Box in a Valise (Fig. 41) they stand

vertically placed beside the miniature of the opus maior. They are (from the top): 1. Paris Air, at the height of the Bride; 2. Traveler’s Folding Item (1916, an Underwood typewriter cover) at the height of the horizon, where the Bride’s cloth is placed; 3. Fountain, placed at the bottom at the level of the Bachelor’s apparatus.

I don’t want to argue a new exegesis of these associations between the three readymades and the corresponding parts of the Large Glass: in my opinion Shearer’s exegesis (located in the second part of her paper) is perfectly convincing. I want instead to underline that at the top and at the bottom of this pile of ready-mades we have two objects referable to the topology of a kleinian bottle (with some straining the intermediate readymade could also be referred to the same topological themes of the others: indeed the cover hints at a well-delimited internal space which however, due to the lack of the bottom, hasn’t a well-defined distinction from the outside, just as in the strange prism of Tu m’. In addition, it is a rubber object; hence it is subjected to the continuous deformations of the rubber geometry, as mathematicians call topology).

This circumstance suggests the attentive reconsideration of the images of the Bride, her iconographic history (the drawing and the painting of 1912, on the subject of the Virgin and of the Bride) and the representation of the Bachelors.

click to enlarge

Figure 42

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride, 1912

Figure 43

Marcel Duchamp,

Sketch of the Wasp apparatus,

Green Box, 1934

The Bride (Fig. 42), mainly in the homonymous painting (1912), is really characterized by a topology at least arduous. We can observe a tangle of pipes or veins connected by rods and pistons, which pass through diaphragms and flow in pouches, swell up in ampoules, are everted in pockets and then drain in canals. Interestingly, none of the parts of this composition starts and ends clearly somewhere. Particularly in the Green Box

we find a sketch where the Wasp apparatus (Fig. 43) is depicted with abundance of captions: it is a sort of cone, internally penetrated by a cylinder, in the vertical sense, which at the top exits from the cone but it remains encapsulated in a sort of niche.

It is difficult to see, in such a tangle, structures which literally replicate the structure of the kleinian bottle, but surely the spatial ambiguity of this hybrid of dissected organisms and mechanical engine hints at a contort topology with no clear distinction between inside and outside, with its labyrinthine self-penetrations and its complex circuital system. After all, the notes that describe the incredible anatomy of the Bride share the same circular and labyrinthine impenetrability. (From this viewpoint we can grasp a subtle continuity between the painting of the Bride and the succeeding Traveler’s Sculpture.)

In the case of the Bride too, the analogy with the topology of the kleinian bottle will be important to the extent that it agrees with the commonly accepted meanings of the work or, even better, to the extent that it can furnish a new interpretative sense. The contort topology of the Bride reflects her (and of the whole Glass) basic feature of closure: both the Bride and the

Bachelors are self-referential machines, totally closed in on themselves.

The cycles of their activity are dramatically turned to themselves, as

Duchamp himself underlines in a note of the Green Box:

Exposé of the Chariot

— Slow life —

— Vicious circle —

— Onanism –

Thus, the working scheme of the Large Glass is a great closed pathway, a labyrinthine annular circuit.

In particular there is an aspect among those of the Bride, described in a note of the Green Box, which explicitly brings us back to the theme of the Mother discussed above. Duchamp says:

“The bride is a motor. But before being a motor which transmits her timid-power–she is this very timid power…”

Here Duchamp proposes once again the idea of the Bride that simultaneously is egg (timid-power) and device to perpetrate the egg’s eternity (motor that transmits her timid-power), i.e. Mother. Duchamp repeated this important concept several times,

with other words, for instance by saying that the Bride is part of the Glass, but simultaneously is the Glass itself. This paradoxical identity between parts and whole (which we already observed with regard to the Bride’s Wasp) perfectly corresponds to the paradoxical identity between inside and outside of the kleinian shapes of Duchamp.

4c. The Autopoietic Machine

The theme of a closed self-referential cycle, connected with the self-creation, has without doubts evocative and fascinating analogies with Maturana and Varela’s autopoietic machine.

An autopoietic machine is a machine organized (defined as a unity) as a network of processes of production (transformation and destruction) of components that produces the components which: (i) through their interactions and transformations continuously regenerate and realize the network of processes (relations) that produced them; and (ii) constitute it (the machine) as a concrete unity in the space in which they (the components) exist by specifying the topological domain of its realization as such a network (Maturana and Varela, 78-79).

This quite difficult definition requires at least some brief explanation. As a system, the autopoietic machine described by the two authors is of parts (or units) and relations between the parts. Parts and relations constitute the structure of the system, and are described by an observer (a human being) that can operate distinctions and specify what he distinguishes as parts and relations. He notes that in such a machine they produce the maintenance and the continuous regeneration of the parts and of the reciprocal relations themselves.