|

|

|

|

“Voici La Mariée détachée de sa robe lubrifiée par les Huiles du Meurt bien appliquées. La Magneto-Libido resplendit de l’effort auprès de la descente de la Roue d’Excentricité sur l’Escalier Maladroit. Ou bien elle se reflette dans la quatrième dimension pour renverser son exploit aux [And now ladies and gentlemen, please welcome, the freed bride at once humorbidly lubricated For more movies, |

All posts by robert

The Bride Achieves Ascendance Moments Before Orgasm, Even

Examining Evidence: Did Duchamp simply use a photograph of “tossed cubes” to create his 1925 Chess Poster?

Introduction

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, Poster

for the Third French Chess

Championship,1925

Rhonda Roland Shearer Collection

Duchamp claimed that he created his 1925 Poster for the Third French Chess Championshipfrom a photograph (Fig. 1). Schwarz writes in his Catalogue Raisonné of Duchamp’s works (708):

To make this image, Duchamp tossed an “accumulation” of building blocks into a net bag, then photographed it, printing an enlargement of the picture that eliminated all details except the chance configuration of the blocks in the net. This enlargement was the basis for the final drawing in which he colored the cubes light pink and black. (1)

Duchamp’s explanation, which sounds direct, simple and plausible, was the basis for the final drawing in which he colored the cubes beige, pinkish brown and black.This explanation has also remained unchallenged by scholars. Francis Naumann writes: “The position of the cubes–their three visible sides colored black, white and beige–was determined, as Duchamp later explained,by tossing them into the air and taking a picture” (101, 103).(2)

If Duchamp’s positioning of the cubes in his 1925 Chess Poster came “readymade”from a photograph that he took of tumbling blocks in a net, then we should be able to take various camera lenses used in 1925, place cubes in the positions depicted, and be able to generate a “photograph”matching Duchamp’s poster.

We tried this experiment using computer modeling and animation software, and made a surprising discovery. In order to co-exist simultaneously in the spatial position that Duchamp depicts in his poster, the individual cubes that Duchamp photographed would have to have interpenetrating surfaces, edges and vertices–a completely different scenario and physical reality from Duchamp’s story of photographing free falling cubes.

Step 1 Look at the Poster itself

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Numbered diagram of the

Poster for the Third

French Chess Championship (1925)

Figure 3

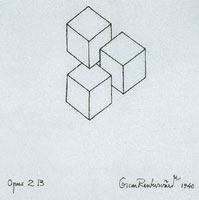

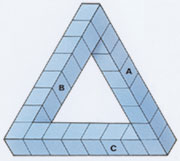

Oscar Reutersvärd,

The Impossible T

ri-Bar, 1934

Examine Figure 2 and more specifically cube 2 or cube 11. The shapes of these cubes, as well as others, appear to be anomalous. In other words,these objects are not symmetrical cubes with six square sides, at right angles to each other and depicted with edges that follow all the rules of perspective, as would be captured by a photographic lens. Cube 2’s black top square appears smaller than the vertical length of its cream colored square, instead of the same size and symmetry as in our expectation and prior experience of cubes drawn in perspective. We note the same situation for cube 16. The pinkish brown cube’s vertical square (on the right side) seems taller than wide, when carefully compared to the shape of the top black square. The more you study these individual cubes by observation alone, even without test or measure, the more maddening the subtle feeling of contradiction becomes–from “yeah they’re cubes” to the eye, to “what the hell, something is wrong with these cube shapes when I compare the squares to each other more carefully”in the mind.

We noted the similarity between the shifting sense from distortion to regularity (or non-cubes to cubes) in Duchamp’s Chess Poster, and a class of optical illusions called “impossible figures” and named by Penrose and Penrose in the 1950s (R. R. Shearer, “Marcel Duchamp’s Impossible Bed and Other “Not” Readymade Objects,”Part I and Part II)(3)Impossible Figures, such as “The Impossible Tri-Bar” discovered by Oscar Reutersvärd in 1934, (See figure 3), characteristically capture us in a cycle of acceptance based on familiar visual cues, followed by a looping back to rejection resulting from nagging contradictory information. Then, after further mental examination, we again visually accept, but then again reject, what we see, ad infinitum. Nigel Rogers, in his book Incredible Optical Illusions, writes about the tri-bar figure: “All those sides appear to be perpendicular to each other and to form a neat, closed triangle. But when you add up the sums of their three right-angled corners, you reach a total of 270 degrees–that is 90 degrees more than is mathematically possible” (62). (4)

In other words,Reutersvärd squeezed into his representation (and into triangles themselves which, in Euclidean space, are defined as limited to 180 degrees) more degrees of freedom than would be allowed by real 3D space. The paradoxical positionings in Reutersvärd’s impossible cube drawings (1934, Fig. 4; 1934 Fig. 5; 1940 Fig.6) remind one of Duchamp’s 1925 chess poster cubes. In fig.5, as you look at the three cubes–you must ask how the two lower cubes can be equal in height at the bottom and of such different heights at the top, yet still be the same size all at the same time? Since Reutersvärd has been credited as the first discoverer and developer of Impossible Objects (before Escher in the 1950s), the chess poster indicates that Duchamp himself was actually first, having predated Reutersvärd by at least nine years. (Shearer previously argued that Duchamp’s impossible bed in the Apolinére Enameled work of 1916-17, indicates that Duchamp already understood the concept of impossible objects, and the optical illusions based upon them, eighteen years before Reutersvärd’s discovery in 1934 (see Shearer, Part I and Part II.)

click images to enlarge

Figure 4

Oscar Reutersvärd, Hommage à Bruno Ernst, perspective japonaise nº 293 a,

Colored Drawing, 1934

Figure 5

Oscar Reutersvärd, Opus 1 nº 293 aa, 1934

Figure 6

Oscar Reutersvärd, opus 2B, 1940

Step 2 Place blocks in position

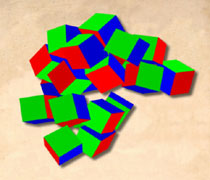

Using SoftImage 3D modeling and animation software as a tool, we placed 21 red/blue/green blocks, following the pattern of the falling cubes in Duchamp’s poster (see Fig. 7A, a video computer animation of our 3D model of red/blue/green shaded cubes, and Fig. 7B an illustration of our 3D model cubes in the places determined by Duchamp chess poster blocks).

- click to see video animation

Figure 7A

The computer animation of 21 red/blue/green

shaded cubes following the pattern

of the falling cubes in Duchamp’s poster - click images to enlarge

Figure 7B

An illustration of our 3D

model cubes in the places determined

by Duchamp chess poster blocks

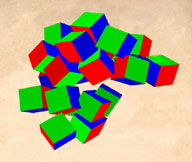

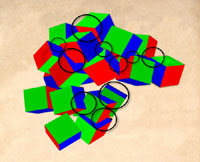

Step 3 Note and then characterize the differences in ten locations

The striking difference in relationships among cubes that we immediately saw when we tried to arrange our red/blue/green blocks into Duchamp’s beige/pinkish brown/black cubes, pattern shows the necessity for imbedding the cubes into each other. With this new arrangement, the odd distortions in the original poster disappeared (see Fig. 8A &Fig.8B, a video animation that circles ten embedded locations and then magnifies the circled area, both in the original poster, and in our 3D model arrangement for making comparisons, and a still image that can be enlarged for study.)

-

click to see video animation

Figure 8A

A video animation that circles

ten embedded locations and then

magnifies the circled area,

both in the original poster,

and in our 3D model arrangement for comparisons -

Click to enlarge

Figure 8B

A still image from the

video animation that can

be enlarged for study

Step 4 What Duchamp appears to be doing–hiding embedding points from the eye but not from the mind

click to enlarge

Figure 9A

Circled area comparison

of blocks 15 and 16 from

both Duchamp’s Chess Poster

and 3D model

Figure 9B

Video animation for the

comparison of blocks 15

and 16 in Duchamp’s

Chess Poster and 3D model

click images to enlarge

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Figure 11

Our numbered diagrams of Duchamp’s

Chess Poster and of

our 3D model illustrate

specific alterations Duchamp

likely made which trick the eye

by use of false perspective cues

(cubes 15 and 16)

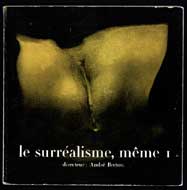

Refer to Figs. 9A and 9B, and to blocks 15 and 16, note the difference between the treatment of these two blocks in the original chess poster and our 3D model on the right. Block 15’s black top-surface in the original poster slices into cube 16 in the 3D model to the right. We learn from comparing Duchamp’s poster to our study model that to “hide” the embedding point of the right cube, Duchamp would only need to extend the brown square’s vertical lines, and to mirror the angle of the square’s top horizontal edge (Fig. 10). Duchamp repeats this approach throughout the poster, as revealed by our 3D model and animation sequence. Note cube 4 in Fig. 11, Cube 4’s top square has been extended and this indicates that the top of cube 4 was originally in front of cube 5 (as in the red/blue/green model now),whereas the final chess poster indicates that the top of cube 4 is behind cube 5. Duchamp’s creation of ambiguity in indicating which figure lies in front or in back represents an original variation upon other optical illusions. Duchamp himself had experimented with many sensory illusions, such as the convex/concave effect that switches back and forth in appearance–convex and near, to concave and therefore farther away. (Duchamp’s Female Fig Leaf and the cover of Surréalisme Même depict the same object.) However, one appears concave, which is the actual state of Duchamp’s object, whereas the convex image on the Journal cover is a retouched photograph with special lighting used to create the optical illusion that Duchamp’s concave object is convex (Figs.12A and B).

click images to enlarge

- Figure 12A

- Figure 12B

- Marcel Duchamp,

Female Fig Leaf, 1950 - Marcel Duchamp, Front cover of

Le Surréalisme, même I (1956)

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Numbered diagram of the

Poster for the Third

French Chess Championship (1925)

We found nothing in the literature of optical illusion that compares with Duchamp’s fascinating approach–that is, of actually embedding cubes together, and then altering them in slight but precise and systematic ways, so as to disguise his tamperings and fool our eyes into believing that several cubes are rationally seen behind others instead of in front (see cube 4 and 5), or that the cubes all have 90º angles (see cube 13) or equal straight edges (see cube 8), all in the same perspective view of one photograph. Partial cubes 18, 19, 20, and 21 were probably strategically placed in order to add to the overall instability of the eye and brain as they attempt to decipher the image. In particular, look at cube 8 and compare the angle and shape of the bottom square to the bigger front face. Note that the bottom edge is not parallel to the top edge above in the same square. Cube 8’s distortions cannot be attributed to a perspective rendering that matches any of the other cubes, or the overall scene (Fig. 13).

As in a baby’s game of peek-a-boo, where one comically switches from seeing with eyes to quick concealment (to what the mind can only see in memory or logic) Duchamp forces you to choose. Duchamp has only temporarily hidden the embedding points of the cube from our eyes (as our eyes accept and do not question his alterations of cubes into objects that are, in fact, no longer shaped like cubes). But he has not hidden this from our minds (which can move from intuition to measuring, and can rigorously detect departures of actual forms from ideal cubes).

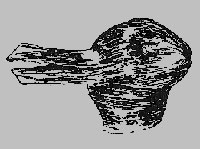

Duchamp’s specific case of the Chess Poster, as its “deception” or optical illusion generally illustrates by direct experience, shows the failure of the retina to reveal reality or truth without the mind. (Philosophers from Helmholz to Thomas Kuhn have often used optical illusions as prototypical proofs for limitation of the eye and mind. In his Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962), Thomas Kuhn famously refers to the content of revolutions in science, such as the change from a sun-centered solar system to an earth-centered cosmos, as both a mental and visual switch, as in our experience with optical illusions of gestalt figures. Kuhn essentially states that scientists who see only Rabbits before the revolution as in a Duck-Rabbit Gestalt figure will suddenly shift, in eye and mind, to seeing only Ducks in the very same places where only Rabbits were observed before (Fig.14). (5)

We believe that the ambiguous cubes in the Chess Poster represent more than Duchamp’s specific triumph in first creating a new class of optical illusion in 1925 (the phenomenon that only Penrose and Penrose later named in the 1950s). We suspect that Duchamp also viewed the creation of this poster as an experiment born of his larger and life-long enterprise in exploring “the beauty of the mind” or “grey matter”–especially as in used in chess, vs. the stupidity of using only the eye or “retina,” an approach that he often castigated.

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Duck-Rabbit Gestalt

In addition to his analogy of chess, Duchamp also claimed that allegorical art (that is,art before “retinal” impressionism) had embraced mental beauty in both the artist and the spectator, for he stated that both shared equally in the creative act. In allegorical art, patterns establish a visual language of forms imbued with universal meanings that are mentally encoded by the artist and then, in turn, must be decoded by the spectator’s mind and eye–a much different experience, Duchamp insists, than that offered by retinal art and sensations in visual experience alone.

Chess itself, by Duchamp’s analogy, is similar to allegorical art because pattern emerges from a set of rules (now as moves in the form of combinations, not as a language of visual forms). Instead of being encoded by the artist and then decoded by the spectator alone, as in allegorical art, chess patterns, also meaningless without a knowledge of rules, require the mind to see combinations of moves, including actions of the opponent, who co-creates moves from within the exchanges between players that emerge in the continual application of these rules, and who must also, just as the spectator does in art, also actively decode physical data into mental meaning.

Just as the shape of the duck/rabbit captures in time [albeit unstably] both a duck and rabbit, physical reality can only hold one belief at a time. (That is, it can be a duck or rabbit.) Duchamp, we believe, capitalizes on the additional possibilities within opticalillusions–for, as representations (as we understand from the 270º of the ambiguous triangle that we recognize as a triangle, but in the physical and Euclidean world would be restricted to 180º) they can be stretched beyond conventional meanings or rules, and even left without full (or even correct) explanation, only to be grasped later by creative acts in spectator’s minds. These spectators now see the chess poster as built from cleverly distorted cubes that stay (for a delay) below the threshold of detection in the very same physical positions where a “readymade” unaltered action photograph of falling regular cubes was seen before.

Step 5 Thinking it over: Could it be that Duchamp is just a bad draftsman?

Our conventional belief that Duchamp’s Chess Poster depicts a set of falling cubes was based upon his claim that he took a photo of falling cubes, and then used the chance positions to create his poster. The geometric shapes that we see in the 1925 poster, perhaps also abetted by the context of chess squares on a chess board, supported a belief that we were looking at multiple cubes, as Duchamp said. (6)

To answer a question with a question, we could ask: is it reasonable to believe that Duchamp’s lack of talent as a draftsman coincidentally led to a consistent and systemic mistake–in other words, that he drew distorted cubes that all happened to become undistorted real cubes when embedded into each other?

It seems to us more reasonable to assume that Duchamp’s various distortions–for example his changing a cube to overlapping in back instead of its correct frontal position–were all used to disguise embedded or intersecting planes.In other words, Duchamp challenges us with objects (in this case cubes) that can appear totally random and free in space, but actually are not, if one uses one’s mind to see. Shearer and Gould’s paper on Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14) presents another case of Duchamp’s use of randomness as a decoy that must be questioned and tested before the real story and facts can be seen with the mind.

This issue of whether or not a phenomenon is, in fact, random remains an important topic in probability, even today. For example, we believe that a coin toss or a lottery is random. However, we can know with a great degree of certainty that the flip or number is not random if someone wins 100 times in a row.Randomness, in fact, is a matter of testing the facts before you, whether you deal with a coin, a roulette wheel or a photograph of chance “falling cubes.”

click to enlarge

Figure 15A

O.R. Croy’s photo trick

uses playing cards to

create the illusion of random, falling objects.

Figure 15B

What is not seen behind

the image of O.R. Croy’s photo trick

In “The Secrets of Trick Photography” by O.R. Croy, we found the following entry that reminds us of Duchamp’s falling cubes (Figs. 15A and 15B). Under the title “The things you don’t see,” this section suggests that photo tricks, such as those seen in fig.15A, create a puzzle “because the way in which they were taken is not obvious.” Croy continues: “It is consequently good to make puzzling pictures of this kind from time to time because it is just as much trouble and excellent practice to the photographer to think out ways and means as it is for the observer to find out how the work was done.” (7) Fig. 15B exposes the trick of 15A. Croy mentions that either a sheet of glass or black background with black thread will work to disguise the supporting structure that creates the illusion.

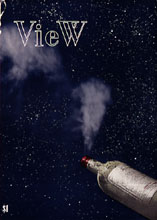

Duchamp often used trick photography from the 1910s throughout the rest of his life (see Figs. 16A and 16B, two trick photographs. Fig. 16A is from 1917, where Duchamp himself appears as a ghost figure, a typical and popular photo trick of that era. Fig. 16B is the 1945 View cover that Duchamp worked to create trick photographic effects. (Also recall the trick photo showing the Female Fig Leaf of 1950 as a convex figure).

- Figure 16A

- Figure 16B

- Studio photogaph (1916-17) appears to have a ghostly

figure of Duchamp,a common and popular photo trick at the time. - Cover of View magazine(1945) is a later example of Duchamp’s

use of trick photography in his work.

Step 6 Considering Alternative Hypotheses

We’ve all heard that if it looks like a duck, quacks like a duck, walks like a duck then it’s a duck. And yet Kuhn told the world that, even in factually based science, a duck can suddenly be seen, metaphorically speaking, as a rabbit. This seems to be a fundamental aspect of the

Click to see video animation

Figure 17

Video animation utilizing

irregular polyhedra shapes instead

of regular cubes to match with

the “cube-like”

shapes in the Chess Poster

creative act–the experience of a new factual reality emerging after discovery. Duchamp, throughout his career, promoted the notion that the spectator must play a 50% role in the creative act. Creating objects that instinctually included the shock of a challenge to factual reality, but that stayed in delay until spectators used their minds to see the mental beauty, seems consistent with Duchamp’s stated goals and purposes indeed.

Suppose however that Duchamp did not use actual cubes to create his poster, what would be the alternative?

We have a second experiment, seen in Fig. 17‘s video animation, where we take irregular polyhedra shapes instead of regular cubes, and then match what we see in the poster. (See Fig. 17‘s video animation that shows the amusing results.)

Notes

1. Arturo Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded paperback edition

1. Arturo Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp, revised and expanded paperback edition

(New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2000) 708.

2. Francis M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: the Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical

2. Francis M. Naumann, Marcel Duchamp: the Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical

Reproduction (Ghent, Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 1999) 101, 103.

3. Rhonda R. Shearer, “Marcel Duchamp’s Impossible Bed and Other “Not” Readymade Objects:

3. Rhonda R. Shearer, “Marcel Duchamp’s Impossible Bed and Other “Not” Readymade Objects:

A Possible Route of Influence From Art To Science,” Part I & II, Art and Academe 10,1 & 2 (Fall 1997; Fall 1998).

4. Nigel Rodger, Incredible Optical Illusions: A Spectacular Journey through the World of the Impossible

4. Nigel Rodger, Incredible Optical Illusions: A Spectacular Journey through the World of the Impossible

(London: Quarto, Inc., 1998) 62.

5. Thomas Kuhn, Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

5. Thomas Kuhn, Structure of Scientific Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962).

6. Arturo Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (2000) 708.

6. Arturo Schwarz, Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (2000) 708.

7. O.R. Croy, The Secrets of Trick Photography (Boston, MA: American Photographic Publishing Co., 1937) 128.

7. O.R. Croy, The Secrets of Trick Photography (Boston, MA: American Photographic Publishing Co., 1937) 128.

Figs. 1, 2, 4, 7A, 9B, 10, 11, 12A, 12B, 13, 16A, 16B

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.

Rarity from 1944: A Facsimile of Duchamp’s Glass

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp,front

cover for View

Introduction

by Thomas Girst

On the last page of Charles Henri Ford’s View (Fig.1) magazine of March 1945 (vol. 5, no. 1), an issue entirely dedicated to Marcel Duchamp, who designed both the front and the back cover, the attentive reader may come across an advertisement (Fig.2) placed left of Duchamp’s famous double portrait (Fig.3) showing the an-artist at both 35 and the then imaginary age of 85.

click images to enlarge

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Advertisment in View magazine, vol. 5, no. 1 (March 1945), p. 54 (detail)

Marcel Duchamp at the age of 35 and 85, in View, p. 54 (detail)

Front cover for Duchamp’s Glass, La Marieé mise à nu par ses célibataires,

même: An Analytical Reflection, 1944

The small ad draws attention to the then recently published book by both the rich art patron and collector Katherine S. Dreier as well as the Chilean-born Surrealist painter Roberto Matta Echaurren: Duchamp’s Glass, La Marieé mise à nu par ses célibataires, même: An Analytical Reflection. (Fig.4) The slim ring-bound volume distributed by Wittenborn and Company, was published in May 1944, in an edition of only 250 copies, by the Société Anonyme, Inc. / Museum of Modern Art, New York.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp, Front

cover for Minotaure,

ser. 2, no. 6

(December 1934)

Figure 6

Marcel Duchamp,

The Bride Stripped

Bare by Her Bachelors,

Even,1915-23

Besides André Breton’s essay “Phare de la Mariée” (or “Lighthouse of the Bride”), first published in French in an issue of Minotaure(Fig.5) in December 1934 ( Paris; ser. 2, no. 6, Winter 1935, cover design: Marcel Duchamp), Dreier’s and Matta’s writing is only the second text and the very first monograph to discuss Duchamp’s major work, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923) (Fig.6) at length and the very first one to appear in English on the subject matter. Breton’s essay appeared in book form not until 1945, within a revised and enlarged edition of Le Surréalisme et la peinture(New York: Brentano’s), a collection of his theoretical writings on painting. An English version did not appear until that same year, within aforementioned issue of View magazine and most likely translated by Charles Henri Ford himself.

Unlike Breton at the time he first wrote his essay, mostly working from an early exhibition photograph (taken when the Large Glass was first shown at the Brooklyn Museum’s International Exhibition of Modern Art Assembled by the Société Anonyme, New York, November 19, 1926 – January 1, 1927; the only time it was exhibited without the cracks) as well as Duchamp’s notes on his Glass published in the Green Box, (Fig.7) both Matta and Dreier had the opportunity to study the Large Glass in the original. Owned by Katherine Dreier and located at her home in West Redding, Connecticut, it was shipped there after its exhibition in early 1927 when it shattered into hundreds of pieces during the transport. It was repaired by Duchamp only about ten years later when he leaves Paris for New York during trip to the US in 1936. (Fig.8) The repaired Glass remains in Dreier’s living room until 1944 until it is brought to her house in Milford. Connecticut, where it is placed before a window between April 1946 to January 1953. In July 1957, under the supervision of Duchamp, it is permanently installed at the Philadelphia Museum of Art where it remains to this day.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 7

- Figure 8

- Figure 9

-

Marcel Duchamp, Front

cover of the Green Box

[deluxe edition],1934 -

Photograph of Katherine

Dreier and Duchamp at her

home in West Redding, Connecticut,1936 -

Marcel Duchamp,

The Passage from Virgin

to Bride, 1912

Together with Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, Katherine S. Dreier (1877-1952), herself an artist, had founded the Société Anonyme, the first museum in America devoted to modern art, a subject on which she frequently wrote. Matta (*1911) came to New York in 1939 and after stumbling upon a reproduction of Duchamp’s The Passage from Virgin to Bride (Fig.9) became infatuated with the older artist who soon thought of Matta to be “the most profound painter of his generation.”

The second paragraph of Duchamp’s Glass reads in full: “The essential principles of human consciousness cannot be grasped until we abandon the psychological attitude of conceiving the image as a petrified thing or object; the result of emphasizing the external vision, which is rarely related to perception. The image is not a thing. It is an act which must be completed by the spectator [my italics]. In order to be fully conscious of the phenomenon which the image describes, we ourselves must first of all fulfill the act of dynamic perception.” Here in this pamphlet, the only known collaboration between Dreier and Matta, a crucial concept of Duchamp is introduced for the very first time. Only years later, in April 1957, the artist himself would elaborate further on the importance of the onlooker during his well-known “The Creative Act,” a brief talk given to the American Federation of Arts Convention in Houston. Within it, he states “the two poles of the creation of art: the artist on one hand, and on the other the spectator who later becomes the posterity.” He concludes that “the creative act is not performed by the artist alone. The spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.”

In this context, it is interesting to note that in 1926, during the Large Glass‘s exhibition in Brooklyn, the Surrealist dealer Julien Levy had apparently noted Duchamp’s later dictum of the fusion of artist and spectator on a mere physical level, remarking upon his initial encounter with this major work: “When I first saw the large glass […] I was fascinated, not merely by the work itself,

click to enlarge

Figure 10

Roberto Matta Echaurren, The

Bachelors Twenty Years

After, 1943

but by the numerous transformations which were lent the composition by its accidental background, by the spectators who passed through the museum behind the glass I was regarding.” (Julian Levy, “Duchampiana,” in: View V, 1 (March 1945), pp. 33-34, p. 34)

Besides three photographs of the Large Glass, a black and white reproduction of Matta’s 1943 paining The Bachelors Twenty Years After (Fig.10) is also included in the 16 page volume, directly incorporating the cracks within. So without further ado, feel free to browse through a scanned version of the scarce original:

Click to browse through

Figs. 1, 3, 5-7, 9

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.

Marcel Duchamp and the Museum of Forgery

When I was in high school, I fell for awhile under the spell of the curious life and work of the Dutch forger Hans van Meegeren. I was particularly struck by how the forger’s art is simultaneously self-aggrandizing and self-effacing, selfish and generous, bold and timid. This early entrancement opened into a broader fascination with dubious artworks of all kinds, especially those that floated on the borders of acceptability–misattributed works, “school of” works, authorized copies, partial fakes, restored works, and so on.

Eventually it occurred to me that the world needed a museum devoted entirely to the subject of forgery. I was thinking of something on the scale of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where all of the world’s most interesting forgeries and fakes, as well as contested works, could find a home. There the works that are normally banished to the basement and the scholar’s office would be displayed in public as rightful exhibits in the great ongoing debate over what constitutes art and how we assign value to objects. At the same time, I realized that very likely no one would ever found such a museum, filled as it would be with works that most people consider valueless and shameful.

In the late 1980s, after the museum idea had lain dormant for awhile, I started using computers as part of my art-making process, and the deceptively simple fact that copies of digital files are perfectly identical to their originals started me thinking again about the relationship between reproduction and value. Around the same time, I happened to be reading Gianfranco Baruchello and Henry Martin’s wonderful book Why Duchamp? and mulling over what is involved in asserting that something is or is not a work of art. It came to me that it would be truer to the paradoxical nature of a museum of forgery if such an institution were dedicated to the practice rather than simply the display of forgery, and I decided to found my own Museum of Forgery along such lines. Display of forgery within the museum raises questions about where the boundary between authentic and inauthentic lies but accepts the idea of the boundary, while practice of forgery within the museum erases that boundary by asserting a fundamental identity between the museum and that which the museum rejects.

A great part of what museums still have to offer of unique value is their institutional authority, a point that Marcel Broodthaers took long ago when he created the Museum of the Eagle. This enduring authority is a second reason why I founded a museum instead of, say, doing a series of projects about forgery. Being the director of a museum gave me a way to speak and be heard on so tendentious a subject as forgery. In this, as in many other aspects, the Museum of Forgery is a child of Marcel Duchamp: it nominated itself as a museum despite the fact that by many definitions it does not belong in that category at all.

Click to go to page

Figure 1

Josef Albers: Studies in

Transmitted Light, 1993,

generic posthumous

albers. A series of digital

works created especially for

the Museum of Forgery to

extend Josef Albers’ reflected

-light color studies into the

realm of transmitted light.

Each image is a study in the

color properties of transmitted

light viewable through such devices

as computer monitors.

In other ways, too, the Museum of Forgery is both museum and anti-museum. It has a permanent collection some of which is now digital, which is to say that a substantial portion of its collection consists of items that are neither objects nor singular. The Museum of Forgery’s first all-digital project was Studies in Transmitted Light, a series of color studies extending Josef Albers’s work with color in reflected-light media, such as paint, to the very different realm of transmitted-light media, such as monitors. (Fig. 1) There is not only no reason to output these works in the realm of material media–say, as paper-based prints–there is every reason not to do so.

What physical collection the Museum has is dispersed; indeed, the Museum has never had a single physical location of any kind where it could be visited. Like most institutions, it is largely façade-a name with a mailing address or, more recently, an Internet address. It isn’t even quite right to say that you can visit it on the web-it would be by loading itself into your browser.(1)

Duchamp the Forger

As the Museum of Forgery unfolded bit by bit, it became clear that one of its chief lines of inquiry was going to be what I loosely call nominalism–artworks in which the primary activity is attaching a new name to something. In semiotic terms, this art of renaming always disrupts an understood link between signifier and signified. In the simplest sense, all art is nominalist: when the artist attaches her signature in the corner, the painting of a landscape becomes no longer “a landscape” but “an O’Keeffe.” The signature bears witness to the creator’s existence, and in doing so elides the distinction between artwork and artist. Both are “an O’Keeffe.” (2)

Forgery, on the other hand, twists the function of the signature, forcing it to bear witness to the actual creator’s absence by pointing to some other more famous person, the creator. Forgers accept that what is key is not who actually created the work but what name is attached to the work (to put it in market terms, they understand the importance of name branding). From this perspective, Marcel Duchamp is more easily understood as a forger than an artist, or perhaps as the first person to really bridge these traditionally opposed fields. Forgery has varying definitions, but most fundamentally it is that-which-is-not-art. However much it may resemble art, it is absolutely excluded from being art. The forger’s object is to pass these absolutely excluded objects into the field of art under the flag of the signature. This effort can never wholly succeed because forgeries have only two ontological statuses: valueless-because-known-as-forgery, and valuable-because-not-yet-exposed. The missing third category is valuable-even-though-exposed; and it is with this category that Duchamp made great play.(3)

When Duchamp attached the name art to various ready-made items by means of the secondary name (signature) Duchamp, he was following the method of the forger. These nominations of ordinary objects as art were a kind of up-front forgery in that they attempted to pass off something understood to be worthless (in the context of art) as something valuable. Duchamp’s method of forgery was unique in several respects. In the first place, even as Duchamp accepted the preeminence of his signature as that which gave the work value, he used it to point away from itself. His nominations tend to cast the emphasis back onto that to which his signature is attached: the thing chosen (a urinal!) tends to displace the act of signing (nominated by Duchamp). In the case of most forgery, by contrast, the signature (a Leonardo!) is enormously more important than the work signed (a painting of something-or-other).

In the second place, he worked in the open, thus unlinking the idea of forgery from the necessity of deceit. In this respect he worked in a mode made so familiar to us by corporate capitalism as to be almost invisible: he attached his brand name Duchamp to an otherwise ordinary object that was actually the product of someone else’s labor. In his work with ready-mades, Duchamp essentially created a new market for a few existing products, and part of his genius lay in recognizing and treating the art world as a modern market–not just a place where artworks were marketed (as it already was), but a place where works of any kind could be marketed as art.

In the third place, Duchamp forged himself. The usual forger forges someone else; that is, nominates one of her own works as a Leonardo or a Picasso. The forger thus appropriates someone else’s name to her own object. Duchamp, however, appropriated someone else’s object to his own name; or, to look at it the other way around, expropriated his name to someone else’s object. Thus, all of his ready-mades were forged Duchamps in the same sense that Van Meegeren’s paintings were forged Vermeers. In both cases the signature does not correspond to the creator of the object.

Excessioning

In selecting works to bear his signature, Duchamp also opened a new line of thinking in which affinity with the work selected becomes more important than the mode of its creation. As in the bulk of his other work, he points away from the reigning mythology centered on “the hand of the artist.” In this also he has something in common with forgers, who must of necessity imitate the hand of particular artists but whose very attempt to do so asserts that the chosen hand is not unique (because imitable) and therefore not worth the supreme value assigned to it.

click to enlarge

Click to go to page

Figure 2

Invasion of the Body

Snatchers, Piazza S.

Gaetano, Naples, 1958/1992,

29 x 21 cm, generic baldessari.

A work commissioned by the Museum

of Forgery and contributed to

the oeuvre of John Baldessari.

The idea of looking at the relationship of artist to artwork as one of affinity rather than production was the spur that led me to form the Museum of Forgery’s Excessioning Program. Under this program, new works are attributed to the oeuvres of appropriate artists, living or dead, regardless of who actually created them. The Museum of Forgery has created (or commissioned) works “by” Marcel Duchamp, Josef Albers, and John Baldessari, among others, as part of its Excessioning Program (Fig. 2).

Just as it sounds, excessioning is an inversion of the normal museum activity of accessioning, reflecting a fundamentally outward orientation, a movement away from the museum itself. By contrast, the existing word de-accessioning reflects the inward orientation of traditional museums: de-accessioning can only be a secondary activity, subordinate to the primary activity of collecting (accessioning). The underlying impulse behind excessioning is to recover a sense of both generosity and honesty in the way artworks are categorized and discussed. Works that are part of a particular aesthetic-a duchampian aesthetic or an albersian aesthetic-are explicitly recognized as such, in contrast to the usual art world practice of concealing and minimizing a new work’s resemblance to its predecessors. (4)

The Excessioning Program models itself on the larger social practice by which well-known trademarks, like Kleenex or Band-Aid, eventually pass into common vocabulary as generic nouns–small-k kleenex–despite intensive and prolonged efforts by the parent companies to prevent this. Manufacturers may be forced by law to use ugly circumlocutions like “facial tissue” on their boxes, but the rest of the world just asks for a kleenex. Similarly, Mona Lisathe brand-name Leonardo has given way to “mona lisa,” a generic that includes Duchamp’s many variations on L.H.O.O.Q. (Parenthetically, it is interesting that Duchamp’s guess that any artwork has a meaningful life span of about 30 years is not far off the patentable life of a commercial product.)

click to enlarge

Click to go to page

Figure 3

Shark’s Pocket, 1992,

11 x 17 x 2 cm overall, generic

posthumous duchamp. A shark’s pocket

made of genuine faux sealskin and

contributed by the Museum of

Forgery to the oeuvre of Marcel Duchamp.

This work is currently on extended

loan to the Museum of the Double.

Similarly, small-d duchamps are generically all those works of art that belong to the aesthetic pool Duchamp himself started. An early Museum of Forgery project was the Shark’s Pocket, a small object of faux sealskin shaped exactly like an ordinary pants pocket (Fig. 3). It has been sewn closed, and concealed inside is a mystery item, the answer to a question I asked myself one day: if sharks had pockets, what would they carry in them? Once it was created, the affinity with Duchamp’s 1916 workWith Hidden Noise and the general absurdity of the premise led me to declare it a generic duchamp.

In the years since I founded the Excessioning Program, I’ve noticed the idea of generics popping up in other contexts–not, I think, as a result of the Museum’s activities so much as a general effect of zeitgeist. I recently heard an artist refer to something she had just made as a “cornell box” and knew instantly what kind of thing she meant. And anyone who has read William Gibson’s 1987 cyberpunk novel Count Zero will remember the artificial intelligence that spends its time making small-c cornell boxes which others then pass off–for large sums of money–as large-C Cornell boxes.

Generics, as the Museum calls the fruits of its Excessioning Program, reflect the cultural shift towards the privileging of information over objects. A duchampian generic is essentially a transmission vector for some of Duchamp’s ideas, which are more important and enduring than any single one of his works. Indeed, even traditional art museums today are less object repositories and sites of pilgrimage than culture transmitters and sites of shopping. In sponsoring manifold replications, from postcards to coffee mugs to replica jewelry, museums function as memetic factories. The vermiform collection exists not to be visited so much as to be reproduced. Museums have become little more than businesses whose primary product is art spin-offs, with large showrooms where their very handsome product templates are tastefully displayed.

Do-It-Yourself Forgeries

It is in part because our attention is currently focused on reproduction in all its varieties that the Internet and other digital media are displacing the museum and the gallery as loci of art activity. In the computer, originals and copies no longer mark out opposite ends of a fixed spectrum but define something more like a field with points of attraction but without fixed positions. The computer is the realm of the original copy, the simulated original, the multiple singularity, the infinite variation.

Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q. works prefigure the fluid metamorphoses of digital art, the return to a practice centered on themes and (valuable) variations rather than originals and (degraded) copies. At one point, he took a group of ordinary postcard reproductions of the Mona Lisa and entitled them L.H.O.O.Q. Rasée (Shaved L.H.O.O.Q.), thus implicitly declaring the Leonardo Mona Lisa a modified version of his own L.H.O.O.Q. Duchamp’s work thus became, by an act of temporal transubstantiation, the original, and Leonardo’s the incomplete copy.

These and other Duchampian projects–such as the authorized Bicycle Wheel replicas–prefigure two other areas of Museum activity, authorized forgeries (Fig. 4) and do-it-yourself forgeries. In order to encourage forgery as a practice the Museum publishes step-by-step directions for re-creating existing artworks. One such DIY project, The Labyrinth of the World and the Paradise of the Heart, can be found on the Museum’s web site (Fig. 5). At the same time, the instructions are loose enough to leave scope for individual variation, as a way of encouraging a new aesthetic of close copies. In Western art since the rise of individualism, it has been impossible for an aesthetic of close copying and subtle variation to arise; close copies are consistently devalued with such terms as “forgery,” “student work,” or just plain “copy.” The DIY forgeries attempt to reclaim the practice of copying by harnessing it to the popular do-it-yourself movement. Although in some respects both nostalgic and a product of mass-marketing–a typically American contradiction–the DIY movement does reflect an underlying belief in experimentation and a championship of making over buying. (5)Paradoxically, creating a do-it-yourself forgery brings the maker much closer to the practice of art than buying a Van Gogh poster in a museum ever could.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 4

- Figure 5

- Snotrags,ca. 1992, approx.

10 x 20 in. overall (not including instructions).

An authorized forgery created by

Yolande McKay for the Museum of

Forgery, this work also doubles as

a kind of prototype for a do-it-yourself

forgery since it includes an

instruction sheet for making one’s

own version of the piece.

The instructions read in part: “Only

a sick person can complete

this forgery….blow your nose or in

some other projectile manner

apply mucoid matter to snotrag

provided….apply forged

signature with small brush and paint.” - Slem Joost, The Labyrinth

of the World and the Paradise

of the Heart, 1992/93,

24 x 32 x 10.5 cm, mixed media.

The original of this do-it-yoursel

fforgery was created by Joost,

a Dutch artist, under the

inspiration of a poem by the

French poet Guillaume Apollinaire.

The Museum of Forgery is now just a decade old. It quite often happens that someone will write the Museum asking to be taught how to counterfeit money or fake antique furniture (apparently without any anxiety over the fact that this might be an indiscreet question to put to a complete stranger). And each time I get such an inquiry, I am reminded again of just how tempting it is to believe that what you see is what you get: despite the evidence of its web site, the Museum of Forgery must be simply what it says it is. In this new age of WYSIWYG (6)everything, the real problem remains the same as ever: what you assume is what you get.

Notes

Work Cited:

Baruchello, Gianfranco and Henry Martin,Why Duchamp? (New York: McPherson, 1985).

1. The Museum of Forgery’s web address is http://yin.arts.uci.edu/~mof/index.html.

1. The Museum of Forgery’s web address is http://yin.arts.uci.edu/~mof/index.html.

2. Formerly, this relationship was made explicit by following the painter’s name with the verbs pinxit or fecit–X painted (made) this therefore X was here-but in current practice, the signature alone stands in for the statement. It has long been common to refer to particular pieces in an artist’s oeuvre as signature works, these being the works considered most characteristic of the artist, and thus most credible as mute witnesses to being.

2. Formerly, this relationship was made explicit by following the painter’s name with the verbs pinxit or fecit–X painted (made) this therefore X was here-but in current practice, the signature alone stands in for the statement. It has long been common to refer to particular pieces in an artist’s oeuvre as signature works, these being the works considered most characteristic of the artist, and thus most credible as mute witnesses to being.

3. There is a fourth category, of course: valueless-although-not-yet-exposed. Although interesting in its own right, it lies somewhat outside the current discussion.

3. There is a fourth category, of course: valueless-although-not-yet-exposed. Although interesting in its own right, it lies somewhat outside the current discussion.

4. A secondary impulse is to extend the terrain that is open to exploration by artists. As matters now stand, in the futile quest for novelty, large areas of the Library of Form are roped off and marked with no-trespassing signs: Property of Brand-Name-Artist X, Keep Out. In some cases the boundaries are enforced by law (especially copyright law), but in many cases the prohibitions are self-enforced by artists who recognize that, as the game is currently played, it is professional suicide to become known as an “imitator” or “follower” of Brand-Name-Artist X.

4. A secondary impulse is to extend the terrain that is open to exploration by artists. As matters now stand, in the futile quest for novelty, large areas of the Library of Form are roped off and marked with no-trespassing signs: Property of Brand-Name-Artist X, Keep Out. In some cases the boundaries are enforced by law (especially copyright law), but in many cases the prohibitions are self-enforced by artists who recognize that, as the game is currently played, it is professional suicide to become known as an “imitator” or “follower” of Brand-Name-Artist X.

5. Although the belief in experimentation is duchampian, the elevation of creating over buying is distinctly un-duchampian.

5. Although the belief in experimentation is duchampian, the elevation of creating over buying is distinctly un-duchampian.

6. [Editor’s note:] Short for “what you see is what you get.”

6. [Editor’s note:] Short for “what you see is what you get.”

Duchamp et Jarry ou l’inverse

Vous ne trouvez ci-après que les lieus où ont été trouvées les citations.Il est à vous de construire les relations–clairement objectives – entre les citations, comme pour le jeu des sept familles.

CITATION I

‘Pourquoi chacun affirme-t-il que la forme d’une montre est ronde, ce qui est manifestement faux, puisqu’on lui voit de profil une figure rectangulaire étroite, elliptique de trois quarts, et pourquoi diable n’a-t-on noté sa forme qu’au moment où l’on regarde l’heure ?”

Alfred Jarry, Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien;Livre IIa, éléments de pataphysique ; VII Définition (Œuvres complètes tome I, La Pléiade, 1972, p. 699)

CITATION II

“M. et Mme Bonhomme (Jaques) … élisant domicile en mon étude et encore à la mairie du Qe arrondissement.” Il s’agit du cabinet de René-Isidore Panmuphle, HUISSIER.””

Alfred Jarry, Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicienLivre premier, Procédure (Œuvres complètes tome I, La Pléiade, 1972, p.657, p. 662) Dans certaines villes, comme à Utrecht aux Pays-Bas, l’administration Napoléonienne à introduit des lettres pour identifier les arrondissements.

CITATION III

“Nosocome, Interne des hôpitaux, actuellement soldat de deuxième classe au Qe de ligne.”

Alfred Jarry, Les Jours et les Nuits (Œuvres complètes tome I, La Pléiade, 1972, p. 776)

CITATION IV

“La Pendule de profil”

Marcel Duchamp, La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même (la “boîte verte”); Lois, principes, phéno-mènes. Plus tard Duchamp ajoutait “Si une pendule est vue de côté, elle ne donne plus l’heure”(Ibid.).Duchamp a construit une pendule de papier pour l’édition de luxe du livre de Robert Lebel, La Double Vue, suivi de l’Inventeur du temps gratuity (Paris, 1964).

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, The

Clock in Profile, 1964

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp, Note from

the Box of 1914, 1914

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp,

L.H.O.O.Q., 1919

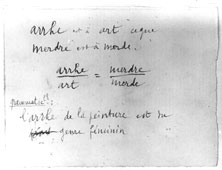

CITATION V

“arrhe = merdreart merde”

La comparaison mathématique de Duchamp se trouve dans la Boîte de 1914. Le mot Merdre est le premier mot d’Ubu roi de Jarry.

CITATION VI

“L.H.O.O.Q.”

“J’écrivis quatre [sic] initiales [au dos de la Joconde] qui, prononcées en français, composent une plaisanterie très osée sur la Joconde” Marcel Duchamp, A propos de moi-même.

CITATION VII

L’ Attente

L’ Envie

L’ Amour

L’ Argent

“Mais ce qui, pour Nadja, fait l’intérêt principal de la page, sans que j’arrive à lui faire dire pourquoi, est la forme calligraphique des L.”est une question non posée par Breton à Nadja à propos d’un brouillon de Nadja.” André Breton dans: Nadja (Œuvres complètes tome I, La Pléiade, 1988, p. 710 et aussi p. 725 et p. 1550).

CITATION VIII

“ARR ist keine Abkürzung sondern ein Urlaut. Immer wenn ein junges Mädchen vorbeiging, reagierte Kurt mit diesem Urlaut … Soviel ich weiss ist nichts über Kurt Schwitters’ Arr-Komplex geschrieben worden.” Kate Steinitz, Kurt Schwitters (Zurich, 1963; “Arr” est prononcé comme “arrth.”)

Il est certain : Duchamp a lu Jarry, Breton a lu Jarry et Breton a connu Duchamp. Les citations ci-dessus ne sont pas forcément la preuve que Duchamp a lu les pages de Jarry où apparaît le Q ou l’horloge, ou que Breton se réfère dans Nadja au L de L.H.O.O.Q. Les citations démontrent

peut-être seulement un `Humour de Lycéen’ partagé par les quatre écrivains.

Figs. 1-3

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.

Die Bedeutung des Ready-mades für die Kunst der Gegenwart

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Marcel Duchamp, In

Advance of the Broken Arm,

1915(studio photograph by Man Ray)

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Fountain, 1917

(photograph: Alfred Stieglitz)

Es sieht so aus, als enthielte das Œuvre Duchamps kein einziges Ready-made im buchstäblichen Sinne. Wie in den verschiedenen Artikeln dieses Magazins nachzulesen ist, hat Rhonda Shearer starke Indizien dafür vorgelegt, daß Duchamp keine ‘echten’ Ready-mades präsentiert hat. Vielmehr handelt es sich bei den‘Ready-mades’ offenbar sozusagen um Fälschungen, also um von Hand hergestellte Imitate der Produkte, die sie zu sein vorgeben, oder um Alltagsgegenstände, die Duchamp gezielt manipuliert hat. (2) Das Fahrradrad eiert, die Schneeschaufel mit dem Titel „In Erwartung eines gebrochenen Arms“ ist für den Gebrauch ungeeignet und selbst die Fontäne ist allem Anschein nach von allen Urinalen verschieden, die Duchamp in einschlägigen Geschäften hätte kaufen können. Hektor Obalk macht darauf aufmerksam, daß die Existenz Duchampscher ‘Ready-mades’ schon ohne dies fraglich ist. Nach der Definition von Duchamp, der zufolge ein Ready-made etwas ist, das durch die bloße Auswahl des Künstlers zu einem Kunstwerk wird, fallen von vornherein eine ganze Reihe Werke heraus, namentlich die, die Duchamp „korrigierte“ oder „assistierte“ Ready-mades etc. nannte. Diese Ready-mades waren von Duchamp sichtbar verändert. Ferner hätte es doch wenigstens einen Fall geben müssen, an denen Duchamp eines seiner Ready-mades einem Kunstwelt-Publikum zugänglich gemacht hätte. Tatsächlich sind zwar durchaus in der Phase seines Schaffens, in der Duchamp sich dem Ready-made gewidmet hat, ‘Ready-mades’ in einer Galerie zu sehen gewesen, allerdings nur in einem einzigen Fall und nicht in den Ausstellungsräumen der Galerie. Die Untersuchungen von Shearer und des ASRL legen damit natürlich um so mehr nahe, die Echtheit der Ready-mades anzuzweifeln.

Diese Entdeckung ist deshalb so verblüffend, weil das Konzept des Ready-mades für die Kunst vor allem der zweiten Hälfte des zwanzigsten Jahrhunderts so wichtig geworden ist. Der Begriff ist aus der Kunst der letzten Jahrzehnte nicht mehr wegzudenken. Entsprechend muß man sich fragen, ob nicht ngesichts der Ergebnisse Shearers diese Kunst ganz neu bewertet werden muß. Im folgenden möchte ich indessen zeigen,

daß die ästhetische useinandersetzung mit dem Ready-made unbeschadet der Tatsache, daß sie auf einem ‘Irrtum’ beruht, weiterhin aktuell bleibt.

Für die Theorie ist die Frage, ob die Ready-mades von Duchamp ‘echt’ sind, natürlich entscheidend. Vor allem für Ansätze, die auf der Ununterscheidbarkeitsthese beruhen, wird die Datenbasis deutlich schmaler, wenn die Werke von Duchamp als Beleg wegfallen: Die Ununterscheidbarkeitsthese besagt nach Danto, daß es Paare von perzeptiv ununterscheidbaren Gegenständen gibt bzw. geben kann, von denen einer ein Kunstwerk ist und der andere nicht; als Bestätigung dieser These kann Duchamp somit, wie es aussieht,

nicht mehr herhalten.

Im Bereich der Kunst sind die Verhältnisse dagegen verwickelter. Kunst bezieht sich auf ihr Material als auf eine gesellschaftliche Realität. Entsprechend ist ihre Selbstthematisierung in der Regel nicht abhängig davon, inwieweit sich aus dieser Reflexion wahre oder falsche Aussagen extrahieren lassen. Kritisch mögen die neuen Erkenntnisse über Duchamp lediglich für solche Projekte sein, deren Pointe Duchamp verschwiegen

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Sherrie Levine,

After Walker Evans, 1979

vorweggenommen hat. Die Originalität verschiedener Strategien des Fake (3) bspw. steht in Frage. Aber selbst in diesem Feld sind die künstlerischen Arbeiten der letzten Jahrzehnte durchaus nicht überholt. After Walker Evans von Sherrie

Levine bleibt interessant, auch wenn die künstlerische Strategie der kalkulierten Fälschung und Entdeckung bereits bei Duchamp zu finden ist. Für das Werk hat Levine Reproduktionen von Fotos von Walker Evans abfotografiert und so Fotos hergestellt, die nicht von Gegenständen sind, sondern von Fotos. Damit erhalten die Fotos eine geistige Dimension, die ihrem Objekt abgehen, obwohl sie diesem –: Fotos von Gegenständen – bis auf die Schärfe genau gleichen: Die Fotos von Evans sind gerade auf Objektivität, auf ihren dokumentarischen Wert berechnet, während die Fotos von Levine ihren Ausdruck durch geringfügigste Differenzen erhalten, die das ansonsten fast unsichtbare Objekt verraten.

Interessanter noch sind aber gerade die Fälle, in denen Kunst sich auf Begriffe bezieht, die unmittelbar mit dem Ready-made zusammenhängen. Als Beispiel mag hier der Zyklus Landschaft von Alexander Ginter dienen. Mit dem Begriff der Landschaft geht Ginter dabei von einem Sujet aus, das dem Ready-made geradezu entgegengesetzt zu sein scheint.

II.

click to enlarge

Figure 4

Alexander Ginter, Landschaft

(Provence), 1999 (installation view)

Bäume, Wiesen und Hirsche haben ihre Zeit gehabt, sollte man meinen. Soweit sie heute noch dazu dienen, unsere Häuser wohnlicher zu machen, hat das weniger mit Kunst zu tun, als mit Dekoration. Wenn sich dennoch ein Künstler der Gegenwart mit der Landschaft auseinandersetzt, kann der Fall entsprechend kaum sonderliches Interesse provozieren. Und doch empfiehlt sich der Zyklus Landschaft unserer Aufmerksamkeit, zumal

insofern er zeigt, wie durch subtile Anspielungen auf innerästhetische Begriffe eine Position gewonnen werden kann, die auch durch eine veränderte kunsthistorische Forschungslage nicht unterminiert werden kann.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Alexander Ginter, Landschaft

(Yucatan), 1999(installaton view)

Der Zyklus besteht aus zwei Teilen. Der erste mit dem Titel Provence ist eine Reihe von Leinwänden, hochformatige ‘Bilder’, die allerdings auf dem ersten Blick eher trist wirken. Der zweite mit dem Titel Yucatan ist eine Installation bestehend aus Fotos und einer linearen Anordnung von Haufen unterschiedlicher Erde. Die Bilder – man ist geneigt Landschaften in Ihnen zu sehen – zeigen im oberen Drittel Silhouetten, Berge vielleicht, in einem Fall eine Art Torbogen oder eine Brücke; die Formen sind schwarz und reduziert auf wenig Charakteristisches, Piktogramme von Landschaften, wenn man so will. Auf dem unteren Teil sehen wir je ein Feld in erdigen Tönen, in braun, gelb oder beige. Tritt man näher an die Bilder heran, so erkennt man, daß es sich bei den bis auf einen Rand von einigen Zentimetern die ganzen unteren zwei Drittel der Leinwände ausfüllenden Flächen nicht um Farbe handelt, sondern um Erde, die auf die weiße Leinwand aufgetragen ist. Unterhalb jedes Bildes findet sich jeweils ein Name: Orte in der Provence. Die Erde, die da aufgetragen wurde, soll man denken, kommt von diesen Orten. Die Bilder beziehen sich also offenbar über das Material auf ihren Gegenstand.

Es bleiben jedoch Zweifel an der Echtheit des Materials. Die Installation, das Arrangement neben der kleinen Galerie von ‘Landschaften’, scheint indessen dieser Skepsis Rechnung zu tragen. Über einem Sims mit neun Häufchen Erde mit rechteckiger Grundfläche hängt eine Reihe Fotos.Diese Fotos bieten sich sozusagen als Beglaubigung für die Echtheit der Erde an. Jedes Foto, so scheint es, zeigt einen Ort, von dem jeweils die Erde von einem der Häufchen stammt.

Das ganze Ensemble wirkt eher schlicht, fast harmlos. Hinter dieser Fassade verbirgt sich indes ein raffiniertes Spiel mit Kategorien und Erwartungen, das uns bei der Betrachtung nach und nach in seinen Bann zieht. Um einen Begriff davon zu geben, seien hier nur einige der Zusammenhänge analysiert.

Das übergreifende Thema des Zyklus ist ‹Landschaft›. Womit wir es aber zu tun haben, sind keineswegs Landschaften im herkömmlichen Sinn, also Landschaften, die sich mimetisch auf ihren Gegenstand beziehen. Das Konzept der malerischen Darstellung selbst wird vielmehr hintersinnig ‘analysiert’, in die begrifflichen Bestandteile zerlegt, und es sind diese Bestandteile, die dargestellt werden: Oben sehen wir die, wenn auch stark reduzierte, ‘Form’ und unten das ‘Material’. Das Verhältnis dieser Ginterschen Bilder zu ihrem Sujet ist dabei durch ihre Materialität wesentlich eines der Methexis an dem, worauf sie sich beziehen. Die Wahrheiten dieser Landschaften ist die Wahrheit

der sinnlichen Gewißheit, von der Hegel sagt, wir „haben uns […] aufnehmend zu verhalten, also nichts an ihm [dem Gegenstand, dem Ding], wie es sich darbietet, zu verändern“. Sie ist „unmittelbar […] die reichste“ und zugleich die „abstrakteste und ärmste“(4) . Jede der Mikrolandschaften, die sich in den Erdflächen verbirgt, ist hoch strukturiert und zugleich fast eintönig, so daß sich aus der Entfernung die Bilder nahezu gleichen. In einer ironischen Wendung gegen das Genre der Landschaft wird hier aus der ‘konkreten’ Landschaft das Konkreteste genommen und nicht abgemalt,

sondern eingeklebt.

Was wir damit vor uns haben, ist die Landschaft als Ready-made, als fertig Vorgefundenes. Das Verfahren erinnert an Picasso, der das Etikett einer Suze-Flasche in ein Bild klebte, um gegen den Realismus in der Malerei zu polemisieren, es wird aber noch dadurch radikalisiert, daß die ‘eingeklebte’ Erde anders als das

Etikett sich nicht einmal für ihre eigene Authentizität verbürgen kann. Für die Serie Provence wird diese Funktion, wenn überhaupt, schlecht und recht von den schwarzen Silhouetten übernommen, an deren Stelle bei der Installation Yucatan scheinbar die Fotos treten. Daß die Fotos die Erdhaufen supplementieren und

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Gerhard Richter, Atlas,

1962-1996(installaton view,

detail of a total of 633 panels)

nicht umgekehrt die Erde die Fotos, wird dabei vor allem durch den Zusammenhang mit den Provence-’Landschaften’ sichtbar. Das Foto als eines der genuinen Medien der Landschaft tritt, weil sich die Erde als ‘eigentlicher’ Stoff des Zyklus darstellt, in den Hintergrund und fungiert als Kommentar. Der Eindruck wird dadurch verstärkt, daß die Bildausschnitte wie zufällig wirken und die Folge der Fotos eher darauf angelegt ist, einander zu einem bestimmten ‘Farbrhythmus’ zu ergänzen, als sich beschreibend oder gar erzählend auf die Motive zu beziehen. Der Umgang mit Fotografie erinnert so an die große Fotoinstallation Atlas von Gerhard Richter, die auf der dokumenta X in Kassel zu sehen war.

Die Pointe der durch die Fotos repräsentierten Authentisierungsstrategie ist indessen, daß sie durch das Arrangement selbst unterlaufen wird. Die Erwartung, daß je einem Erdhaufen ein Foto entspricht, wird enttäuscht, denn tatsächlich haben wir neun Erdhaufen, aber zehn Fotos. Dadurch wird der Verdacht genährt, die Erde stamme vielleicht gar nicht von den angegebenen Plätzen. Allerdings ist unklar, was im Falle der Gleichzahligkeit von Erdhaufen und Fotos durch die Fotos überhaupt bewiesen würde.

Wir werden hinsichtlich der Herkunft des Materials verunsichert. Nicht nur der Begriff der Landschaft wird hier also reflektiert und in Frage gestellt, auch das Konzept des natürlichen Materials und insbesondere das der Authentizität werden thematisiert und kritisch durchleuchtet.

III.

Die Interpretation macht deutlich, daß der Begriff des Ready-mades, des schon fertig Gemachten, Vorgefundenen, außerordentlich wichtig für die Landschaft ist, ohne daß die Installation in diesem Begriff aufgeht. Vielmehr wird das ‹Ready-made› für eine Auseinandersetzung mit dem Thema ‹Authentizität› und dem Genre der Landschaft in Anspruch genommen und weiterentwickelt. Das gilt unbeschadet der Tatsache, daß eine unmittelbare Auseinandersetzung mit Duchamp hier nicht intendiert ist. Die durch den Duchampschen Begriff vermittelte Auseinandersetzung, und nicht dessen Applikation ist das, was den Zyklus so interessant macht.

Solche Arten der Aneignung werden durch die neuere Forschung zu Duchamp in der Tat nicht widerlegt: Auch andere Begriffe, denen in der Realität nichts entspricht oder die in sich widersprüchlich sind, wie die des Äthers oder der Dreieinigkeit, haben ein außerordentliches kreatives Potential freigesetzt; wo sich die Kunst mit solchen Konzepten auseinandergesetzt hat oder wo diese wie auch immer implizit in sie eingegangen sind, ist die Kunst nicht dadurch entwertet worden, daß die Begriffe für uns ihre Relevanz eingebüßt haben. Es sind die Theorien, die bei einer Revision unserer Begriffe ihre Gültigkeit verlieren, nicht die Kunst.

Das gilt übrigens auch da, wo die Kunst selbst theoretisch wird. Entsprechend geben die Untersuchungen des ASRL eher Anlaß zu der Erwartung, daß der Einfluß Duchamps auf die gegenwärtige Kunst fortbestehen wird, als daß die Kunst der letzten Jahrzehnte entwertet würde. Die Theorie der Kunst kann sich dagegen nicht damit begnügen, die neuerliche Finte Duchamps achselzuckend zur Kenntnis zu nehmen, auch wenn gegenwärtig die Neigung dazu groß ist.

Notes :

1. Wichtige Ideen des zweiten Teils verdanke ich Constanze Berwarth und Elsbeth Kneuper (vgl. Michael Enßlen: Kunst als Kultur der Präsenz, Heidelberg 2000). Die Verantwortung für den Text trage ich.

1. Wichtige Ideen des zweiten Teils verdanke ich Constanze Berwarth und Elsbeth Kneuper (vgl. Michael Enßlen: Kunst als Kultur der Präsenz, Heidelberg 2000). Die Verantwortung für den Text trage ich.

2. Hektor Obalk, “The Unfindable Readymade” , Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1.2 Articles (May 2000)

2. Hektor Obalk, “The Unfindable Readymade” , Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 1.2 Articles (May 2000)

3. Eine umfassende Studie hat jüngst Stefan Römer vorgelegt: Künstlerische Strategien des Fake. Kritik von Original und Fälschung. Köln 2001. Vgl. Auch Hillel Schwartz: The Cultur of the Copy. Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles.

3. Eine umfassende Studie hat jüngst Stefan Römer vorgelegt: Künstlerische Strategien des Fake. Kritik von Original und Fälschung. Köln 2001. Vgl. Auch Hillel Schwartz: The Cultur of the Copy. Striking Likenesses, Unreasonable Facsimiles.

New York 1996.

4. G.W.F. Hegel: Phänomenologie des Geistes, Hrsg. Hans Jürgen Gawoll, Hamburg 1986, S.69.

4. G.W.F. Hegel: Phänomenologie des Geistes, Hrsg. Hans Jürgen Gawoll, Hamburg 1986, S.69.

Figs. 1, 2

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.

Jarry = Duchamp

click to enlarge

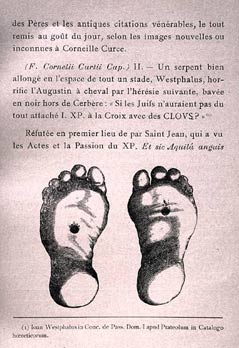

Figure 1. Anonymous

Woodcut of Jesus’ feet

1. Jarry

“La Passion: Les Clous du Seigneur”.

2. Duchamp “Sculpture-morte”

click to enlarge

Figure 2. Marcel Duchamp

Torture-Morte

1959

Painted plaster and

flies, on paper mounted

on wood, 11 5/8 x 5

5/16 x2 3/16 inches

(29.5 x 13.4 x10.3 cm)

Illustration to Alfred Jarry’s article,

“La Passion: Les Clous du Seigneur”

L’Ymagier IV

(July 1895)

Page 221

Spencer Museum of Art

Museum Purchase: R. Charles and Mary Margaret Clevenger Fund, 94.32

Fig. 2

©2002 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.

All rights reserved.

A Note on Linda Dalrymple Henderson’s “Duchamp in Context” (Niceron, Leonardo, Poincaré & Marcel Duchamp)

Figure 1

Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Duchamp in Context: Science and Technology in the Large Glass and Related Works, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1998)

Figure 2

Portrait of Jean Francois Niceron (1613-46), 1646

Figure 3

Marcel Duchamp, Cover for A l’infinitif [a.k.a. The White Box],

1967

The recent discovery by Rhonda Shearer of the influence of the Renaissance geometer Niceron on Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass (note from White Box) is confirmation of both his debt to Poincaré and his status as a sophisticated geometer in his own right.

The formidable academic scholarship of Professor Henderson may tend to limit the overall influence of Poincaré in favor of a “smorgasbord mix”

of contemporary science on Duchamp’s formulation of the Large Glass. In another context, the brief introduction by Prof. Henderson of Niceron missed an important contribution to the understanding of M.D.’s approach to Optics and Perspective.

Similar to his friend Apollinaire, Duchamp, in lieu of academic training, immersed himself in intensive studies of Optics and Perspective (as opposed to the generality of Apollinaire’s varied studies) in the St. Genevieve Library becoming, also a savant of the history of ideas. More information about Duchamp makes it untenable to deny the focus of Duchamp on Poincaré’s ideas, as proposed in “Science and Method” and “Science and Hypothesis.”

A concern with Optics and Perspective is common to Duchamp, Poincaré and Leonardo (in his Notebook). This focus on the geometry of vision is inseparable from the physiology of vision and the mechanics governing perception. Such a density of material, presented to even the most sophisticated public, might require a “light touch” (not of the hand, so despised by Duchamp) in presentation. Comic relief is afforded by such notions as “hilarious invention.” Niceron himself, in “La Perspective Curieuse,” is at no loss for subtle jokes at the expense of the Pope’s Turkish foes!

Figure 4

Marcel Duchamp, Plate of Eau & Gaz à tous les étagesaffixed to the box for the limited edition of Robert Lebel’s Sur Marcel Duchamp, 1958

Blake wrote, “energy is eternal delight.” This sums up the pervasive erotic element which everywhere humanizes Duchamp’s exploration of the theme of a universal energy which ascends from the prosaic “Bachelor Realm” to the higher dimension proper to the “Bride.” This vary complex being, the Bride, seems to embody a gradient of stages (gas on all floors) from the strictly mechanical, to the electromagnetic, to the Wasp of Fabre, the etymologist, to Rrose Sélavy and — perhaps — in some empyrean splendor, the Virgin Mary herself.

The concept of a continuum of progressive states from the micro to the macro-scotic realms is essential to both Poincaré and Duchamp. Such a progression implies, at some point, a separation in dimensions which nonetheless still communicate. Thus, the Bachelor Realm is redeemed from isolation and yet supplied the gross fuel, which undergoes transformations as a distilled essence, at last arrives to nourish the Bride and to enable her, in turn, to provide for the limited world of the Bachelors a way of transcending their prescribed orbits, clothed in liveries and uniforms of stultifying conformity.

Everywhere this continuum appears buffeted by chance or, more accurately, refined by chance, so that an alternative to the dead stasis of thermodynamic equilibrium is revealed in the universal play of energy states–as well as in the mind as in Nature. As chance has its play in the mind, Poincaré brings forward a theory of human creativity and genius, in the chapter formulation, following an intensive but more or less random input of study, ideas appear to sort themselves out in what he calls the unconscious mind. There follows “tout fait,” the illuminating flash of insight. This vividly recalls Kekules’s epochal discovery of the benzine ring. Poincaré elaborates on this process from his own experience; service in the army only served to grant him a time for unconscious reflection on a problem. Freed of military obligations, he was struck all of a sudden with a path to a solution to his problem. Of course this epiphany had to be paid for in the laborious working out of the happy inspiration!

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even [a.k.a. The Large Glass], 1915-23

In accordance with his universal postulate of collisions producing phenomena–from random collections of dust mites (an important Duchampian motif) to the vast interstellar space of the Milky Way where flaming gases mingled following principles laid down by Clerk Maxwell–all nature, including Mind, was subject to a process in which destined outcomes proceeded in an orderly fashion from inputs randomly fed into closed systems. Similarly in the mind of genius, ideas, like molecules, collided and bumped against each other. At length, the closed system of the unconscious mind sorted out the most fruitful outcome, giving rise to a new paradigm.

This is the central theme of the Large Glass. Through an almost the “illuminating gas” arises and, becoming increasingly refined, passes from the three dimensional realm of the Bachelors into the higher fourth dimensional realm of the Bride. This process mirrors in contemporary form the transmutations that the alchemists made with the array of crucibles, furnaces, alembecs, etc.

When confronted with the suggestion he was an alchemist, Duchamp replied, “If I have practiced alchemy it has been in the only possible way that it can be practiced today, namely unknowingly.”

The thesis, shared by Duchamp and Poincaré, infers that any effort to place Duchamp in any other orbit (*pun intended) than that of Poincaré is to deny M.D.’s consistency and his basic seriousness, however concealed by the rubric of “playful physics” or “hilarious picture.” A very serious mind has addressed the basic problem of human creativity. In so doing, he has adopted as a model the thoughts of a leading mathematician and physicist of his day. Without Poincaré, the Great Glass would lack cohesion and relevance to seminal modern thought. Duchamp would have spent so many years of thoughtful labour in vain (neglecting the dreary months of repairing his masterwork in Katherine Dreier’s garage after it was shattered by careless handling); producing only a witty commentary on contemporary science.

*Poincaré was a foremost astronomer interested in the three-dimensional problem.

Without wishing to in the least diminish Linda Henderson’s monumental work, Duchamp in Context, the writer seeks to put Duchamp in a leading place in the history and development of science–not as an original theoretician or as an experimentaist in any but a “thought experimentalist mode.” (Remember that Einstein’s great discoveries came from the use of imaginative “thought experiment.”) The notes for the Great Glass, in themselves, furnish an extraordinary essay in thought experimentation. Without intensive academic training, without a well-furnished laboratory, without consistently available help from hired co-workers or staff, Duchamp’s commentary on science has much to do with Jarry’s pataphysics.

Pataphysics, as Jarry himself defines it, consists of, “the science of imaginary explain the universe supplementary to this one.” The writer believes that the universe supplementary to this one could only be apprehended from a higher dimensional standpoint, attainable solely through mathematical insight. This would confirm that Duchamp had recourse to the brilliant insights of Poincaré, who above all others at the time understood the inter-dimensional tensions between the familiar third-dimensional world and the so-called fourth, where the fourth is a spatial dimension (five dimensions would include time). Such tensions, according to Duchamp and Poincaré, could be resolved in the subconscious mind following an intensive period of effort or study. (The phrase “tout faite,” in fact, originated with Poincaré.)

Jarry’s pataphysics were propounded (posthumously) by his character Dr Faustroll. The so-called laws of science were, according to the doctor, merely exceptions occurring more frequently than others. This skeptical iconoclasm gave rise to Duchamp’s notion of “playful physics.” Perhaps the concept of “meta-irony” would better serve than any other to characterize Duchamp’s approach to “exact science.” His mentor Poincaré was applying a statistical, probabilistic model to descriptions of that range of phenomena, dust mites to galactic gaseous formations, already referred to.

The intrusion of probabilistic consideration into exact science displaced an earlier confidence in Determinism–followers of Newton and Laplace Physicists, e.g. Einstein, were uncomfortable with a world in which “God played dice.” Although a fervent amateur of advanced science, Duchamp was nevertheless capable of a gentle (and very intelligent) mockery of that which so fascinated him.

In Niceron, Duchamp may have seen a quality of “hiddenness.”

By this the writer refers to the use of “folded prisms and multiple viewpoints to convey unsuspected images, lurking,” as it were, awaiting detection–as with Duchamp’s ‘Wilson-Lincoln effect,’ Rhonda Shearer has consistently drawn attention to the quality of ‘hiddenness’ in the oeuvre of Duchamp. This is not obscurantism; although there is a traditional linkage to the obscure language of the classical alchemists.