In a well-known Spanish medical publication called MD, diverse articles relating to anomalies in art were often published: the elongation of El Greco´s figures was the result of a distortion produced by squint; Goya´s black paintings were due to progressive lead poisoning; Van Gogh´s flaming colors, a particular case of schizophrenia. Perhaps because of this and other reasons, I ended up associating Duchamp (MD) with a picturesque uncle of mine, a doctor and subscriber to this magazine in the sixties. A connection that surely underlay one of my dreams where Duchamp appeared camouflaged with my uncle, as if he were another member of the family.

The dream consists of a family reunion, which takes place in a room whose atmosphere, from what could be seen through a french window, was redolent of Paris or Buenos Aires. In a cinematographic black and white, the effect of contrasted lights and shadows reproduced a saturated masculine ambiance –somewhere between Bogart and Gardel- characteristic of the first detective movies. No one speaking, we were all there, our silhouettes cutout against the window’s resplendence while a river grew torrentially outside, sweeping debris along the street. Shortly after, much like the effect of an acetate about to burn, the image acquired a reddish tone, gradually dissolving into the face of Marcel, who ended up with his hair tinged of a red oxide, a color between minium and brick, as one of his “bachelors” or, why not, like a cosmopolitan Adam in a two-piece suit about to ignite.

This reference to a distinctly masculine universe makes me think of gentlemans’ purveyers and of the goods themselves : cigars, pipes, cards, dice, liquor cases, gaming tables lined with green cloth, roulettes, domino pieces, chess boards… some of the elements extensively and enigmatically used in cubist imagery, along with instruments and music scores.

Figure 1

Marcel

Duchamp, Monte

Carlo Bond, 1924.

Except for chess, which was an obsessive presence in Duchamp´s life, the only one of his works related to these types of games, more specifically to Roulette, is that known as the Monte Carlo Bond (Fig. 1), dated November 1, 1924, the year after leaving his masterpiece The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even (1915-1923) ‘definitely unfinished’. This is also the year that marks his legendary and supposed retirement from art, and his move towards the more rarified and abstract world of chess.

The Monte Carlo Bond or Obligation pour la Roulette de Monte Carlo is a ‘rectified and imitated readymade’, a lithograph for a real document, a bond issued in 30 numbered exemplars each with a value of 500 francs. The original bonds, commercial obligations used to release a certain sum on a defined date with a determined rate of interest, were redesigned and released by Duchamp with the purpose of collecting funds in order to experiment with a mathematical system in the game of Trente-et-Quarante, using a Martingale(1) that would allow him to win ‘slowly but surely’ over the Monte Carlo bank, thus making roulette to behave like a chess game.

Placed directly over the ‘radiant’ image of a roulette wheel in the lithograph, is a curious photograph of Duchamp with his hair and face covered in foam. In the lower part of the document, inscribed on the roulette table there are two signatures : Rrose Sélavy’s (Duchamp´s feminine alter ego, here starring as President of the Administrative Council,) beneath the black diamond; beneath the red one, as simple administrator, is Marcel’s. Printed in the background and repeated 150 times in green ink, is a game of words of the capricious harvest of Rrose Sélavy: moustiques domestiques demistock (domestic mosquitoes half-stock).

But let us first see how some authors have described this image:

|

David Joselit: “a lithograph including a portrait by Man Ray of Duchamp transformed through shaving cream into a chimerical figure perhaps resembling a faun or devil (…) Marcel, like Rrose, is masquerading as a hyper-masculine devil or faun.” (2) Dalia Judovitz:“a self-portrait of his head covered with shaving foam and his hair pulled up into horns, further destabilizes the authority of this financial document.” Calvin Tomkins: ”A Man Ray photograph of Duchamp’s head -the face lathered with shaving soap and the hair soaped into two devilish-looking horns”. (4) Peter Read: “a colored lithograph representing the surface of a roulette table with a photograph of Duchamp’s head covered with shaving foam, his hair pulled up into the horns of a faun or devil, stuck onto the roulette wheel which forms a surrounding circle, similar no doubt to the halo which, in Henri-Pierre Roché’s eyes, Duchamp always wore. Cut out (decapitated) from a larger photo by Man Ray, Duchamp’s head resembles that of John the Baptist presented on a plate with his erect horns of hair ready to be shaved off, the male falls victim to both Salomé and Dalila –a powerful recurrence of serrated symbolism.”(5) Juan Antonio Ramírez: “The most striking visual element of the raffle tickets printed by Duchamp is his own effigy, resembling a faun (achieved with shaving soap), against the background of a roulette wheel. This is one way of giving a human story-line to a mechanism, a means of bestowing sexuality on it; here again is the satyr-bachelor trapped in his masturbatory circularity, hoping to acquire the lounged-for winnings after each of the croupier’s ‘manipulations’[“This was admitted by A. Schwarz, who quoted Freud: ‘A passion for gambling is equivalent to the ancient compulsion to masturbate.”] But perhaps there is something more, an allegory of the artist and his chance reward.” (6) |

click to enlarge

Figura 2

Giambologna, Mercury, 1576.

Figura 3

advertising Notice

Figura 4

ad from Patek Philippe

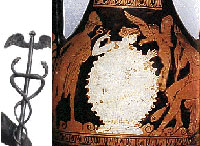

General consensus seems to be that Duchamp’s lathered head is like that of a faun or devilish figure. On a closer look however, the foamy shapes above Duchamp’s head do not correspond to the traditional horns of devils or fauns; instead, their shape is strongly evocative of one of the principal attributes of classical antiquity’s messenger god Mercury (Fig. 2). Curved back in their own particular manner, these forms match Mercury’s winged traveler’s cap known as petasus, as can be clearly seen in Giambologna’s sixteenth-century bronze statue, rather than the short erect horns normally belonging to fauns and devils.

Is it not curious that in the different readings Duchamp´s face is repeatedly interpreted as a faun, a demon or a satyr, as a masculine being necessarily supplied with horns? This interpretation is fostered not only when thought of in connection with the ‘diabolic’ artistic-financial operation of the Tzanck Check of 1919,(7) but also by images of the aforementioned creatures in classical mythology in which beard and horns appear simultaneously to characterize them. The horns, as history of art dictates, would proceed from the beard.(8)

Iconographically, the Roman god Mercury –or Hermes as he was known in ancient Greece— is suggestively pertinent to Duchamp’s financial document. Renowned for his speedy effectiveness, resourcefulness, and shrewdness, Mercury was the Roman god of trade, profit, merchants, travelers, and shepherds, as well as patron to artists, impostors, and all dishonest folk.(9) In addition to the winged cap, Mercury was endowed with wings for his feet called talaria, a caduceus or rod entwined with serpents, and a purse as symbol of his commercial powers.(10) Even his name resonates with these associations; deriving from the Latin root for merchandise, a mercibus, the name Mercury underlies the term ‘mercantile’. Indeed, these are all attributes intensely associated with Duchamp’s conduct, which may be summarized in his anagram: marchand du sel, or salt merchant.

Beginning at about this time (1924), this kind of behavior was accentuated when, along with his renewed passion for chess, Duchamp embarked in a series of negotiations and artistic-financial speculations. Such an attitude is well synthesized in the advertisement of the Flying Wheel (Fig. 3), a wheel with wings, identical in essence to the collage over the roulette: a popular synthesis, if you like, of a good part of Duchampian iconography.

Thus, Duchamp’s Mercurial image not only bears an iconographic resemblance to the ancient god but is also conceptually tied to the activities surrounding the Monte Carlo Bond. Moreover, Duchamp’s disguise may be read on yet another level, one with deep personal implications, as shall be developed throughout this essay. For what we see in the photomontage is a bearded Mercury, as he appeared in some archaic Greek vases, but which is rather unusual in later imagery, where he is generally shown beardless, almost feminine.(11) Duchamp’s use of foam for creating a beard (as an adolescent in front of a mirror conjuring up virile fantasies) (Fig. 4) exalts this ambiguity, for it simultaneously indicates the absence of a beard after shaving and the appearance of a false beard in place of a real one.

Duchamp’s obsessive capillary experiments, and the consequential psychological negotiations between various identities begins casually in 1919, in Buenos Aires, when he shaves his head as a part of a treatment to reduce hair loss. This confers him a rather marginal aspect in the widest sense of the word, whether as an initiate in some sort of sect – chess?(12)-, as a convalescent man –his friends find him excessively thin- or simply delinquent (13).

On his return to Paris in the midst of 1919, in a gesture that clearly anticipates the creation of his feminine pseudonym Rrose Sélavy, he creates the well-known readymade of the Mona Lisa (L.H.O.O.Q.) adding a mustache and Mephistophelean small beard to the image. At the end of 1921, after the aromatic transsexual display of Rrose Sélavy presented as Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette on the altered label of a lugubrious flask of Rigaud perfume,(14) (Fig. 5) he creates a tonsure on his head in the form of a comet with its tail projected towards his forehead. (Fig. 6)

Three years later, immediately after the self-portrait in the Monte Carlo Bond –in Cinésketch, a theatrical diversion of Picabia and René Clair- Duchamp reappears as Adam in a tableau vivant based on a sixteenth-century painting by Cranach, (Fig. 7) displaying an evidently artificial beard (a significant counterpart to the ambiguous beard of foam), a watch, and a shaved pubis. Certainly not the last ‘shaving’ in his work.

click to enlarge

Figura 5

Figure 5 Rrose Sélavy, 1921. Photo Man Ray

Figura 6

Marcel Duchamp, 1921.

Figura 7

Adam and Eve. Marcel Duchamp and Bronja Perlmutter. Paris, 1924.

###PAGES###

2

In contrast to the horn theory, which focusses interpretative attempts on the nature of the monetary operation, the hairdo with wings might lead to a different interpretation, especially when we consider that the hermetic Mercury appears with his hair and beard covered in foam. An evanescent material indicative of some activity, foam is a composite of bubbles produced by an insistent battering movement where air is incorporated into a liquid of some density (in this case, soap). A substance fraught with multiple sexual and poetic evocations as revealed by its etymology: Foam, in Greek, is Aphros, the origin of Aphrodite (or Venus), the goddess born from the sea’s foam.(15) This element offers an important clue for deciphering the identity(16) of the unusual portrait, by setting out with the following equation: Hermes + Aphrodite = Hermaphrodite.(17)

Figure 8 ,Roulette

This androgynous combination could be interpreted as some kind of mythological correction made by joining Mercury’s communicative capacity (exemplified in the movement of the roulette) (Fig. 8) with the perfection of potential success in the ‘figure’ of gambling(18)which is indirectly represented through Aphrodite’s attributes (love, beauty, sexual passion) of two human entities in conflict: Rrose Sélavy, the ‘widow’ whose signature appears beneath the black diamond(19) , and Marcel Duchamp, the confirmed ‘bachelor’ who signs as “administrator” under the ancestral red one(20).

Figure 9

Marcel Duchamp,

Rotorelief disk, 1935

The structure of this Obligation reveals the duplicity involved in the names and colors corresponding to each one of the diamonds, as well as the eventual convergence in the central image of the hermaphrodite as third element. With each turn of the wheel, the red and black loose their identity through the increasing speed of the movement, and end by fusing their specific identities into what in Duchamp’s terms may be called a gris de verticalité… “as all axes disappear in the gris de verticalité, the front and back, the reverse and obverse adopt a circular significance…”(21)

In analogous manner, the roulette not only continues (in another format and on a different topological level) the inter-dimensional speculation attributed to his Bicycle Wheel of 1913(22) and the perceptual experimentation of optical devices related to the Témoines Oculistes (Oculist Witnesses) in the lower part of the Bride Stripped Bare, but also incorporates chance (a characteristic element of the game of roulette) as a necessary element. In this way, the legendary duality of the Bride Stripped Bare is subverted by a third element: the androgyne, an option for the incomplete couple of a fresh widow and an untamed bachelor.

Figure 10

Durer, Adam and Eve, 1504.

Referring to the general principle of the illusory effect of his twirling spirals, Duchamp wrote: “I only have to use two –eccentric- circumferences and make them turn over a third center.” (Fig. 9)

To visualize the symbolic effect of this curious ‘dissolution’, one has only to imagine a displacement of the frontal point of view of an archetypal image, as for example Durer’s Adam and Eve (Fig. 10). If instead of looking at the image from a frontal position, we place ourselves over the image and look at it from a bird’s eye view, from a roulette type of perspective, we notice that the vertical axis (the natural hinge represented by the tree), as well as Adam and Eve (Marcel/Rrose; red/black) have been transformed into three points aligned on a plane.

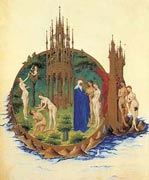

Figure 11

Limbourg Brothers,Temptation &

Fall,before 1414

If we now imagine a circular Paradise, as in some early representations (Fig. 11), and we make our first parents (re-péres: references) circulate rapidly around the central point, there will be a moment where the traditional position (Adam at the left; Eve at the right) disappears. We can no longer speak of right and left, for these occur simultaneously –as in Pawloski’s La Diligence Innombrable (23) – in all locations at the same time. All differences are reconciled as long as the ubiquitous and instantaneous velocity lasts. Speed and motion, a strategic resource used by Duchamp throughout his life as a hypothetical solution to psychological emergencies.(24)

Duchamp’s obsession with the synthesis of opposites(25) also manifests itself in the arrangement of the head in relation to the roulette’s circular form which, deep down, is nothing other than a bull’s eye or target. (Fig. 12) The coincidence of the right eye with the center of the wheel nullifies, in principle, the distance between the observer and his objective, between the self and the world, for structurally the perspectival system consists of a reciprocal identity between the point of view and the horizon point.(26)By superposing the right eye with the center of the roulette, Duchamp conjures up not only his intention of succeeding in the prediction of the bet,(27)but also perfectly illustrates the unitary principle of conciliation.

Figure 12

emoins Oculistes, detail

(the right eye in the center)

and roulette with green zero

Jarry, in relation to the unusual language of Bosse-de-Nage, his character in Exploits and Opinions of Doctor Faustroll who only said “HA HA”, refers to the formula of the principle of identity: “A Thing is Itself.” “Pronounced quickly enough, until the letters become confounded, it is the idea of unity. Pronounced slowly, it is the idea of duality, of echo, of distance, of symmetry, of greatness and duration, of the two principles of good and evil.”(28)

On the other hand, the difference (in relationship) between The Bride Stripped Bare and the Monte Carlo Bond lies in that in the former the separation is external (bachelors looking for their couple) while in the latter it is internal (the incorporation of Rrose Sélavy by hermaphrodite ‘infusion’) projecting the target, the objective, onto itself.

The strategy of the lathered image inscribes itself in the precise game of identities offered as a form of escape, or renovated compensation, for an artist who is clearly over burdened by his intense immersion during the past eight years in the complexities and contradictions of the drama underlying The Bride Stripped Bare: the Bride above(29), the Bachelors below, and the difficulty of connecting these two dimensions through one of the last devices in process, that of the Témoines Oculistes, an optical apparatus whose purpose is to help overcome the threshold of an almost forsaken horizon standing between the Bride and the Bachelors.(30) Significantly, Duchamp left the work ‘definitely unfinished’…as is indicated in the final adverb of the complete name of the work: The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors, Even.

Literally, the Monte Carlo Bond is then a unifying tie, the ‘bond’ between two ancient and opposite entities, represented by the traditional colors of the roulette. This duality is fragmented in an exemplary manner into 37 numbers disseminated in the oracle-like vertigo of the roulette(31) , optically nullifying (through the ‘indifference’ produced by speed) the abysmal separation into an androgynous instantaneous paradise.

In the fifties, speaking of the relationship between chess and the roulette, Duchamp tells Arturo Schwarz that both games involve “a struggle between two human beings”, which he tries to reconcile by “turning the roulette into a more cerebral game, and chess into a game of chance”. And in 1968, the last year of his life, in a conversation with Lanier Graham, he specifies: “The symbol is universal. The Androgyny stands over philosophy. If one has turned into the Androgyny then philosophy is no longer necessary.

”(32) (32)

###PAGES###

3

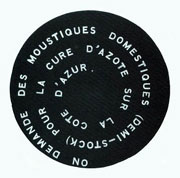

But behind the rapid wings and the weightless foam, stands always the sea, a sea that is indicated in various locations: 1. the location of Monte Carlo itself; 2. in the nature of the shaving foam transformed into Aphros, ‘sea-foam’; 3. hidden behind the insistent tongue twister moustiques domestiques demi-stock that is repeated 150 times in green ink(33) much like a ‘security slogan’ in the background of the Obligation. The phrase is nearly identical to Nous livrons à domicile /des moustiques domestiques /[demi-stock](34) , the same phrase that appears completed, three years later, on one of the discs of Anemic Cinema(35): “ON DEMANDE DES MOUSTIQUES DOMESTIQUES [DEMI-STOCK] POUR LA CURE D’AZOTE SUR LA CÔTE D’ÁZUR.”

That “cure d’azote sur la Côte d’Azur”, can also be found camouflaged in the back of the Obligation’s statutes:

Art. 1er. –La Société a pour object:

1º L’explotation de la roulette de Monte-Carlo dans les conditions ci-après.

2º L’explotation du Trente et Quarante et autres mines de la Côte d’Azur sur délibération du Conseil d’Administration.(36) .

Figure 13

Anemic Cinema disc

The Anemic Cinema disc (Fig. 13) would then be a verbal collage somewhere between the lemma printed in the Bond’s background and the Côte d’Azur named in the statutes, which is phonetically transformed into Cure d’Azote (generally translated as ‘nitrogen cure’). The Anemic Cinema disc indirectly introduces the term Azoth, a word whose significance transcends the simple summer Mediterranean oxygenation.

Azoth necessarily refers us to alchemy (a metaphoric background which, together with modern science and psychology, abounds in Duchampian exegesis) where the three basic symbolic substances (mercury, sulphur, and salt) are complemented with a fourth one, the mysterious vital principle known as Azoth. This primus agens is seen by some as “the invisible, eternal fire; others as electricity; still others as magnetism.

Transcendentalists refer to it as the astral light.” Also described as “primitive air” and as “the Waters or Crystalline Chaotic Sea”(37) , the key virtue of this mysterious ingredient consists in bonding together the physical matter represented in the three basic substances. And it is this unifying virtue that causes some to identify it as “unconditional love”. A sort of generic glue whose powerful and subtle nature cannot be wholly scrutinized.

Existing documents allow us to suppose that around the time of the Monte Carlo Bond, Duchamp was going through a particularly critical moment. And although (as usual) his reserved nature strategically covers the details, in the sixties, towards the end of his life, he writes: “Since 1923 I consider myself as an artist ‘défroqué’ [unfrocked].”(38) “Thus, after 1923, -according to Jean Clair- came a time of disillusion and apathy. Duchamp défroqué. Duchamp idle. Duchamp the chess player.”(39)

In a maternal approach, Katherine Dreier, one of his patrons, considered that the psychological atmosphere of a casino was detrimental “for a person as sensitive as Marcel”. And Breton: “How could a man so intelligent –the most profoundly original man in the century, according to Breton- devote his time and energy to such trivialities? Searching for an explanation, Breton could only conclude that some hidden malaise must be at work –what he had described to Jacques Doucet as Duchamp’s ‘desperate’ state of mind.”(40) Nevertheless, in the spring of 1924, before the Monte Carlo Bond, Duchamp writes to Jacques Doucet after one month at the Riviera during a chess tournament: “The climate suits me perfectly, I would love to live here.”(41)

Therapy? ‘Oxygenation’ in Monte Carlo? Perhaps the encapsulated air in the foam is of the same nature as the Air de Paris, his readymade from the early 1920s. Originally a glass phial filled with physiological serum -bought and emptied by Duchamp in a Parisian pharmacy, and then presented as a souvenir to the Arensberg upon his return to New York – Air de Paris can be seen as a translation of the 50cc of Parisian air into a ‘psychological serum’. All this, the same year when Rrose Sélavy is ‘born’.

Figure 14

Rrose Sélavy, Belle Haleine,

Eau de Voilette, 1921

After her first manifestation retaining the copyright of Fresh Widow (French Window) — a French window condemned in its visibility by glass panes covered in brilliant black leather— Rrose Sélavy is presented visually on the name and label of Un Air Embaumé originally a perfume of Rigaud rebaptized as Belle Haleine, Eau de Voilette. (Fig. 14) Another psychological serum, although rather lugubrious, judging from the initial case: a small coffin where the image of the rigorous and concentrated transvestite slides through.

This problematic identity foreshadows the foaming Monte Carlo portrait, and allows us to imagine the deep significance behind the “exploitation of Thirty and Forty and other mines of the Côte d’Azur under the deliberation of its Administrative Council.” In other words, under the deliberation of its only two members; what Duchamp calls on other occasions “un petit jeu entre Je et Moi”. And apropos of dualities, the mercurial portrait, as any medal, must have another face. The opposite image -in my view- is not the beautiful and radiant head of John the Baptist or that of the sedated Holofernes as has been suggested, but is instead the image of that who lays fearful of her own reflection upon Perseus’s shield: Medusa. Deadly force that petrifies whoever looks at her. A true evil eye. An evil ‘Voilette’.

Figure 15

Cellini, Perseus and Medusa, 1545-54

Why Medusa? Because of Perseus: “Mercurial, aerial, Perseus is unique in being able to conjure the gravity of things, the opacity of chaos, the numbness of Saturn’s weighty world …there where the spirit, too tied to earth, becomes frozen in its fear of petrification.”(42) Because Perseus, like Mercury, carries on his helmet and sandals the same rapid and ethereal wings.(43) And also, because in the axis of that tree, the serpent twirls around like a Caduceus, symbol of medicine [MD] and transformative power. Another indispensable attribute of Mercury, where the two opposite animals, the bird and the serpent, determine the significance and polarity of the implicit process: the serpent as material energy associated with the ascendant spiral and the bird as liberated, spiritual form. The relationship with Perseus is then didactically illustrated at the moment when Perseus, his head covered with the winged helmet, exhibits Medusa’s severed head, sustaining her mangled hair made up of serpents in a symmetrical, mirror-like manner.(44) (Fig. 15)

It is therefore not beyond reason to suppose that the reverse of the circular self-portrait in the Monte Carlo Bond (its corresponding negative image) is Caravaggio’s image of Medusa (an actual shield) painted at the end of the sixteenth century.(45) Interestingly, it is often said that Caravaggio used his own features as the model for this round image, while gesticulating in front of a mirror. Thus allowing us to propose the following iconographic relationship: (Figs. 16, 17 & 18)

|

|

|

|

Figure 16

|

Figure 17

|

Figure 18

|

|

Caravaggio, Medusa, c.1597

|

Azoth.Union of the 3 elements: mercury, sulphur and salt

|

Marcel Duchamp, Air de Paris, 1920

|

In this sequence, the ‘ petrification’, the detention or apathy felt by Duchamp in the period following The Bride Stripped Bare would necessitate a certain ‘ breathing space…or draft of air’ (a courant d’air) that could revitalize his faculties as ‘respirator’: “I like living, breathing, better than working (…) if you wish, my art would be that of living: each second, each breath is a work which is inscribed nowhere, which is neither visual nor cerebral. It’s a sort of constant euphoria.”(46) In this particular circumstance, the nature and secret of the euphoric and constant element could not be found in the habitual cultural ‘nutrition’ -that is in his reinscription into artistic and social activity- but in the timeless properties of an essential symbolic scenery: the sea, and chance. The crystalline, chaotic waters; effectively, a cure d’azote sure la Côte d’Azur – geographical location of immersion and baptism where the annexed feminine (Aphrodite/Rrose) establishes a natural and mythic complicity. An element in front of which, reason and logic (with all their intentions and grueling calculations) see themselves compelled to negotiate between the metaphoric territories of the combative (masculine) chess, and the roulette’s whimsical chance.

The serum, the glass bubble with its ethereal air of Paris is nothing else than a necessary ‘azoth’, a sensitive order freely incarnated in that alter-ego with the name of a rose, a flower imbedded with the liberating energy of eros. Thus we can imagine graphically how Caravaggio’s asphyxiating Medusa incorporates the revitalizing virtue of azoth as a kind of medicinal potion, transforming itself. The result may be fully appreciated in the Monte Carlo ‘cameo’ with the foaming head encrusted in the solar aura of the roulette.

Figure 19

Birth of Venus, with Hermes

(holding Caduceus) and Poseidon

L’Obligation d’un Possible? A feasible Bond? In any case, a secret unconscious martingale throwing its bet over the lingering target of a much-needed self-regeneration. A new birth of a Je and a Moi unified as a pearl in its shell generated by the Chaotic ‘gambling’ Sea of Monte Carlo. A very personal system where Duchamp nevertheless, “never wins nor loses”(47) , in natural compliance with that central point, indifferent, of the “et-qui-libre”(48) hermaphrodite.

On the other hand, the synthetic figure of the Bond, the underlying instrument to the whole therapeutic process is none other than the Caduceus, (Fig. 19) the winged rod with the two symmetrically intertwining serpents. This object may be associated – via Tiresias – with the alternating masculine/feminine sex, and with the oracular gift of prophecy. In this context, the story of Tiresias is quite pertinent:

Celebrated prophet of Thebes…It is said that in his youth he found two serpents in the act of copulation…and that when he had struck them with a stick to separate them, he found himself suddenly changed into a girl. Seven years after he found again some serpents together in the same manner, and he recovered his original sex by striking them a second time with his wand. When he was a woman, Tiresias had married, and it was from those reasons, according to some of the ancients, that Jupiter and Juno referred to his decision a dispute in which the deities wished to know which of the sexes received greater pleasure from the connubial state. Tiresias…declared that the pleasure which the female received was ten times greater than that of the male. Juno, who supported a different opinion…punished Tiresias by depriving him of his eyesight… But…Jupiter…bestowed upon him the gift of prophecy, and permitted him to live seven times longer than the rest of men.(49)

Vedi Tiresia che mutò sembiante

Quando di maschio femmina divienne,

Cangiandosi le membra tutte quante;

E prima, poi, ribatter li convenne

Il due serpenti avvolti, con la verga,

Che riavesse le maschili penne.”

(Dante, Divina Commedia. Inferno, Canto 20:40)

In more recent times, in 1944, Poulenc created a musical adaptation of Apollinaire’s 1903 piece Les Mamelles de Tiresias (Tiresias’s Breasts). Both versions remove themselves from the original tale in a significant and burlesque manner, transposing the hermaphrodite sexual alternation into domestic terms. The modern narrators relate a decline in France’s birth rates due to the feminine emancipation of Thérèse/Tirésias, a loss compensated by her husband who gave birth to 40,000 children in one day… In any case, Poulenc decided to transfer the action of Apollinaire’s version from Zanzibar, an island near the African east coast, to Zanzibar, a supposed population on the French Riviera somewhere between Nice and Monte Carlo. All because he adored Monte Carlo and also because “that was where Apollinaire spent the first 15 years of his life”, adding that this was a place “sufficiently tropical for a Parisian like myself.”(50)

In the end, Duchamp did not become an addict to roulette, but instead submerged himself for the rest of his days in the sophisticated infra-mince labyrinth of the strategic possibilities offered by chess. In relation to Monte Carlo, in 1952 he sums up his adventure by saying: “Artists throughout history are like gamblers in Monte-Carlo and in the blind lottery some are picked out while others are ruined… it all happens according to random chance. Artists who during their lifetime manage to get their stuff noticed are excellent traveling salesmen but that does not guarantee a thing as far as the immortality of their work is concerned. And even posterity is a terrible bitch who cheats some and reinstates others, and reserves the right to change her mind again every 50 years.”

But perhaps, the clue for transcending history and not simply being subject to random chance is as claimed by a commercial slogan of some web page: “with caduceus you’re not a number… you are an individual!”.(51) In other words, you must pronounce Zanzibar! Zanzibar! “quickly enough, until the letters become confounded”.

Notes

1. “The Martingale is a very old and extremely simple system for recovering betting losses by progressively increasing the stakes. It is based on the probability of losing infinite times in a row and is usually applied to ‘even money’ bets.” For this definition of the Martingale, see < http://ildado.com/roulette_rules.html >![]()

2. David Joselit, Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp, 1910-1941. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1998.![]()

3. Dalia Judovitz, Unpacking Duchamp: art in transit. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1995.![]()

4. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: a biography. New York: H. Holt, 1996. ![]()

5. Peter Read, “The Tzank Check and Related Works by Marcel Duchamp”, Marcel Duchamp Artist of the Century, edited by Rudolph Kuenzli and Francis M. Naumann. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1989.![]()

6. Juan Antonio Ramírez, Duchamp, Love and Death, Even. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 199![]()

7. This piece was created by Duchamp as an imitation of a real check drawn upon The Teeth´s Loan & Trust Company, Consolidated, an invented bank, with which he paid his dentist Daniel Tzanck a sum of $115 dollars.![]()

8. That people have read the foam-created forms as horns may also be due to the Dionysiac connections implicit in the game of words resulting from Duchamp’s pseudonym Rrose Sélavy (Eros, c’est la vie). However, this type of eroticism is more readily connected with an essentially vitalist oeuvre, as is Picasso’s, rather than with Duchamp’s, which may be characterized as mental and elaborate.![]()

9. For “all things Mercury” see http://www.hermograph.com/science/mercury.htm Go to the link about the god Mercury for the history, symbolism, and legends surrounding the ancient god, and see in particular his “Work History”.![]()

For Mercury´s thievish activities, see the entry for Mercurius, in John Lemprière, Classical Dictionary.(1788) London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1984, p.373-374.

10. For ancient representations of Mercury endowed with his various attributes see Gregory R. Crane (ed.) The Perseus Project, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu August, 2002. See the references to Mercury under Greek and Roman Materials: 109. Boston 98.1135 which shows a silver coin bust of Mercury wearing his winged petasus with caduceus; 122. Boston 98.676 which shows Mercury with his purse.![]()

11. For images of a bearded Mercury, see Gregory R. Crane (ed.) The Perseus Project, http://www.perseus.tufts.edu August, 2002. See the references to Hermes under Greek and Roman Materials: 28. Louvre G192; 68. Toledo 1956.70![]()

12. From Buenos Aires, Duchamp wrote to Walter Arensberg in 1919: “I play chess all the time. I’ve joined a local club, where there are very good players grouped according to grade. I have not yet been honored with a grade. (…) I play night and day and nothing in the world interests me as much as to find the right move… I am less and less interested in painting. Everything around me is knight shaped or Queen shaped and the outside world only interests me in as much as it transposes into winning or losing positions.”![]()

13. In Wanted, dated 1923, a work immediately previous to the Monte Carlo Bond, he personifies as such in a reward poster. This was later used as the poster for his retrospective exhibition at the Pasadena Museum in 1963.![]()

14. Originally, Un Air Embaumé. A balm, a perfume; an ‘embalmed’ air, as well.![]()

Fig. 1, 5-7

![]() 15. According to Hesiodus, Aphrodite was born when Uranus (father of gods) was castrated by Chronos, his son. When Uranus fell to the sea, his genitals produced foam. From aphros, or the sea’s foam, Aphrodite was born, and later drawn to Cyprus or Cythera, the paradisiacal isle of Watteau’s renowned painting.

15. According to Hesiodus, Aphrodite was born when Uranus (father of gods) was castrated by Chronos, his son. When Uranus fell to the sea, his genitals produced foam. From aphros, or the sea’s foam, Aphrodite was born, and later drawn to Cyprus or Cythera, the paradisiacal isle of Watteau’s renowned painting.

![]() 16. More than a recreation of Duchamp’s conscious or unconscious intentions, this interpretation of the Monte Carlo Bond is an act of reconstruction in the interpreter. An analogical projection on a proposed riddle, where ‘the public, the interpreter, makes the work’.

16. More than a recreation of Duchamp’s conscious or unconscious intentions, this interpretation of the Monte Carlo Bond is an act of reconstruction in the interpreter. An analogical projection on a proposed riddle, where ‘the public, the interpreter, makes the work’.

![]() 17. Not as their son (as in the mythological account where Hermaphrodite is born from Hermes and Aphrodite, but is originally a masculine being who only later becomes androgynous after meeting the nymph Salmacis) but as a symbolic fusion of the two. For the story of Hermaphroditus, see Lemprière, p.277.

17. Not as their son (as in the mythological account where Hermaphrodite is born from Hermes and Aphrodite, but is originally a masculine being who only later becomes androgynous after meeting the nymph Salmacis) but as a symbolic fusion of the two. For the story of Hermaphroditus, see Lemprière, p.277.

![]() 18. Duchamp writes to Picabia in a letter of 1924: “Le problème consiste d’ailleurs à trouver la figure rouge et noir à opposer à la roulette (…) Et je crois avoir trouvé une bonne figure. Vous voyez que je n’ai pas cessé d’être peintre, je dessine maintenant sur le hasard.” DDS p. 269.

18. Duchamp writes to Picabia in a letter of 1924: “Le problème consiste d’ailleurs à trouver la figure rouge et noir à opposer à la roulette (…) Et je crois avoir trouvé une bonne figure. Vous voyez que je n’ai pas cessé d’être peintre, je dessine maintenant sur le hasard.” DDS p. 269.

![]() 19. As in 1920, in Fresh Widow: a French window painted of a ‘mint’ green color, whose glass panes have been supplanted with black leather. In accordance with Duchamp’s instructions, these had to be constantly shined ‘as if they were shoes’.

19. As in 1920, in Fresh Widow: a French window painted of a ‘mint’ green color, whose glass panes have been supplanted with black leather. In accordance with Duchamp’s instructions, these had to be constantly shined ‘as if they were shoes’.

![]() 20. “Adam: to be red. Some writers (…) assign to the word adam the twofold signification of “red earth”, thus adding to the notion of man’s material origin a connotation of the color of the ground from which he was formed.” See www.newadvent.org/cathen/01129a.htm

20. “Adam: to be red. Some writers (…) assign to the word adam the twofold signification of “red earth”, thus adding to the notion of man’s material origin a connotation of the color of the ground from which he was formed.” See www.newadvent.org/cathen/01129a.htm

![]() 21. See Algebraic Comparison (of the Green Box of 1914). DDS, pg. 45. Third note pertaining to the Preface and to the Warning, seminal notes in the writings of Duchamp.

21. See Algebraic Comparison (of the Green Box of 1914). DDS, pg. 45. Third note pertaining to the Preface and to the Warning, seminal notes in the writings of Duchamp.

![]() 22. In Ulf Linde, Cycle, La roue de bicyclette. Marcel Duchamp, Abécédaire. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1977. And also inscribed in the sequence of circular chronology: Coffee Mill, Chocolate Mill, Propeller (the declaration to Léger and Brancusi towards the end of 1912 in the 4th Salon de la Locomotion Aérienne: “Painting is over. Who could do it better than this propeller?”), Bicycle Wheel, Rotative Plaque Verre, Discs with Spirals, Monte Carlo Bond, Door of 11 of rue Larrey (somehow summarized in the door of the Gradiva Gallery of 1937), Rotoreliefs, etc.

22. In Ulf Linde, Cycle, La roue de bicyclette. Marcel Duchamp, Abécédaire. Paris: Centre Georges Pompidou, 1977. And also inscribed in the sequence of circular chronology: Coffee Mill, Chocolate Mill, Propeller (the declaration to Léger and Brancusi towards the end of 1912 in the 4th Salon de la Locomotion Aérienne: “Painting is over. Who could do it better than this propeller?”), Bicycle Wheel, Rotative Plaque Verre, Discs with Spirals, Monte Carlo Bond, Door of 11 of rue Larrey (somehow summarized in the door of the Gradiva Gallery of 1937), Rotoreliefs, etc.

![]() 23. See the chapter La Diligence Innombrable in Voyage to the Country of the Fourth Dimension, a scientific novel by Gastón de Pawlowski, published for the first time in 1910. According to some declarations by Duchamp, this novel was influential for certain speculative notions applied to the Bride Stripped Bare. Jean Clair develops this idea extensively in his book Marcel Duchamp ou le Grand Fictif. Paris: Editions Galilée, 1975.

23. See the chapter La Diligence Innombrable in Voyage to the Country of the Fourth Dimension, a scientific novel by Gastón de Pawlowski, published for the first time in 1910. According to some declarations by Duchamp, this novel was influential for certain speculative notions applied to the Bride Stripped Bare. Jean Clair develops this idea extensively in his book Marcel Duchamp ou le Grand Fictif. Paris: Editions Galilée, 1975.

![]() 24. The fastest and perhaps most significant period of Duchamp’s development (1912), beginning with Nude Descending a Staircase and King and Queen Traversed by Fast Nudes (and variants), to Airplane, where velocity is a fundamental factor for confronting the static petrification of certain ancient references.

24. The fastest and perhaps most significant period of Duchamp’s development (1912), beginning with Nude Descending a Staircase and King and Queen Traversed by Fast Nudes (and variants), to Airplane, where velocity is a fundamental factor for confronting the static petrification of certain ancient references.

![]() 25. In The Spirit Mercurius, Jung says: “Mercury truly consists of the most extreme opposites; on the one hand he is undoubtedly akin to the godhead, on the other he is found in sewers.” And in Psychologie et Alchimie, Hermes/Mercury “is the primordial hermaphrodite being that divides itself to form the classic couple brother-sister, unifying itself later in the conjunctio in order to finally reappear under the radiant form of the Lumen Novum, of the Lapis.” The hermaphrodite is also ‘the philosophical Adam, still with his rib…’

25. In The Spirit Mercurius, Jung says: “Mercury truly consists of the most extreme opposites; on the one hand he is undoubtedly akin to the godhead, on the other he is found in sewers.” And in Psychologie et Alchimie, Hermes/Mercury “is the primordial hermaphrodite being that divides itself to form the classic couple brother-sister, unifying itself later in the conjunctio in order to finally reappear under the radiant form of the Lumen Novum, of the Lapis.” The hermaphrodite is also ‘the philosophical Adam, still with his rib…’

![]() 26. “Physiquement -L’œil est le sens de la perspective.” DDS, p.123.

26. “Physiquement -L’œil est le sens de la perspective.” DDS, p.123.

![]() 27. “Le jeu du tonneau est une très belle sculpture d’adresse.” DDS, p.37. A popular game where the objective is to insert metal rings over metallic frogs -or toads- placed on a box with numbered holes.

27. “Le jeu du tonneau est une très belle sculpture d’adresse.” DDS, p.37. A popular game where the objective is to insert metal rings over metallic frogs -or toads- placed on a box with numbered holes.

![]() 28. Alfred Jarry, Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, London: Jonathan Cape, 1965, p. 228-229.

28. Alfred Jarry, Selected Works of Alfred Jarry, edited by Roger Shattuck & Simon Watson Taylor, London: Jonathan Cape, 1965, p. 228-229.

![]() 29. This position makes one think of the Bride as a transformed Aphrodite, originally an ancient Asiatic goddess similar to the Mesopotamic Ishtar and the Syrian goddess Astarté, in addition to the Virgin. Or in Duchamp’s own words: “the apotheosis of Virginity”.

29. This position makes one think of the Bride as a transformed Aphrodite, originally an ancient Asiatic goddess similar to the Mesopotamic Ishtar and the Syrian goddess Astarté, in addition to the Virgin. Or in Duchamp’s own words: “the apotheosis of Virginity”.

![]() 30. This was fulfilled only later in a casual manner, when the Bride and the Bachelors –in the clamoring style of Jarry- literally broke the glass in the midst of an accidental copulation while they were transferred (after the work’s first and last exhibition in intact form at the Brooklyn Museum, to Connecticut), one panel on top of the other, in a truck.

30. This was fulfilled only later in a casual manner, when the Bride and the Bachelors –in the clamoring style of Jarry- literally broke the glass in the midst of an accidental copulation while they were transferred (after the work’s first and last exhibition in intact form at the Brooklyn Museum, to Connecticut), one panel on top of the other, in a truck.

![]() 31. 18 black and 18 red, plus a green zero in the European roulette; the American version uses a double zero.

31. 18 black and 18 red, plus a green zero in the European roulette; the American version uses a double zero.

![]() 32. See Lanier Graham, “Duchamp and Androgyny: The Concept and its Context,” Tout-Fait, vol.2, Issue 4 (January 2002) Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/volume2/issue_4/articles/graham/graham1.html>.

32. See Lanier Graham, “Duchamp and Androgyny: The Concept and its Context,” Tout-Fait, vol.2, Issue 4 (January 2002) Articles <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/volume2/issue_4/articles/graham/graham1.html>.

![]() 33. Green is also the color of zero, a unique oasis –together with the color of the game board—flanked by a black 26 and a red 32 [VOISINS DU ZERO! in roulette argot] in a numeric version of that ineffaceable scene of the Western imagination.

33. Green is also the color of zero, a unique oasis –together with the color of the game board—flanked by a black 26 and a red 32 [VOISINS DU ZERO! in roulette argot] in a numeric version of that ineffaceable scene of the Western imagination.

![]() 34. Marcel Duchamp, Posthumous Notes #s 227, 234, 249 y 279.

34. Marcel Duchamp, Posthumous Notes #s 227, 234, 249 y 279.

![]() 35. This was a film of 7’ created in 1926 with the help of Man Ray and Marc Allégret, where discs with word games about Rrose Sélavy written in spiral form alternate with abstract patterns of Discs with Spirals (created two years before) and turn hypnotically inside out.

35. This was a film of 7’ created in 1926 with the help of Man Ray and Marc Allégret, where discs with word games about Rrose Sélavy written in spiral form alternate with abstract patterns of Discs with Spirals (created two years before) and turn hypnotically inside out.

![]() 36. DDS. Sur l’Obligation Monte-Carlo, p.268.

36. DDS. Sur l’Obligation Monte-Carlo, p.268.

![]() 37. See www.volcano.net/~azoth/newpage1.htm and http://azothgallery.com/index.htm

37. See www.volcano.net/~azoth/newpage1.htm and http://azothgallery.com/index.htm

![]() 38. The priest who hangs his habits. On the one hand, in Laforgue’s sense: “The idea of liberty would be to live without any habits (…) a whole existence without a single act being generated or influenced by habit. Every act an act in itself.” Revue Anarchiste, 1893. On the other hand, as a specific incapacity: ”l’impossibilité du fer (du faire).”

38. The priest who hangs his habits. On the one hand, in Laforgue’s sense: “The idea of liberty would be to live without any habits (…) a whole existence without a single act being generated or influenced by habit. Every act an act in itself.” Revue Anarchiste, 1893. On the other hand, as a specific incapacity: ”l’impossibilité du fer (du faire).”

![]() 39. “In two reappraisals, at least, other than this manuscript, Duchamp would explain his state of being ‘ défroqué’.” The first time, in 1959, to G. H. Hamilton, he confided, “It’s true that I really was very much of a Cartesian défroqué – because I was very pleased by the so-called pleasure of using Cartesianism as a form of thinking, logic and very close mathematical thinking.” (Interview with the BBC, in London, September 14-22, 1959.) A second time, in 1966, he confided in the critic Pierre Cabanne that, “Depuis quarante ans que je n’ai pas touché un pinceau ou un crayon, j’ai été vraiment défroqué au sens religieux du mot…” (Entretiens avec P. Cabanne, “Je suis un défroqué” in Arts-Loisirs, Paris, no. 35, May 25 – 31, 1966, p. 16-17.) In Jean Clair, “Duchamp at the Turn of the Century”, Tout-Fait, vol. 1, Issue 3 (December 2000) News <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_3/News/clair/clair.html>.

39. “In two reappraisals, at least, other than this manuscript, Duchamp would explain his state of being ‘ défroqué’.” The first time, in 1959, to G. H. Hamilton, he confided, “It’s true that I really was very much of a Cartesian défroqué – because I was very pleased by the so-called pleasure of using Cartesianism as a form of thinking, logic and very close mathematical thinking.” (Interview with the BBC, in London, September 14-22, 1959.) A second time, in 1966, he confided in the critic Pierre Cabanne that, “Depuis quarante ans que je n’ai pas touché un pinceau ou un crayon, j’ai été vraiment défroqué au sens religieux du mot…” (Entretiens avec P. Cabanne, “Je suis un défroqué” in Arts-Loisirs, Paris, no. 35, May 25 – 31, 1966, p. 16-17.) In Jean Clair, “Duchamp at the Turn of the Century”, Tout-Fait, vol. 1, Issue 3 (December 2000) News <http://www.toutfait.com/issues/issue_3/News/clair/clair.html>.

![]() 40. Both of these references are in Tomkins, p.261.

40. Both of these references are in Tomkins, p.261.

![]() 42. Jean Clair, Méduse. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1989. p.93. The original text in French reads: “Mercuriel, aérien, Persée est seul à pouvoir conjurer la pesanteur des choses, l’opacité du chaos, l’engourdissement du monde pesant du Saturne …là où l’esprit, trop rivé à la terre, se fige dans l’épouvante de sa pétrification.”

42. Jean Clair, Méduse. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1989. p.93. The original text in French reads: “Mercuriel, aérien, Persée est seul à pouvoir conjurer la pesanteur des choses, l’opacité du chaos, l’engourdissement du monde pesant du Saturne …là où l’esprit, trop rivé à la terre, se fige dans l’épouvante de sa pétrification.”

![]() 43. See Lemprière, p.464-466, for the story of Perseus. Interestingly, it is Mercury who gives Perseus the winged sandals when Perseus is about to embark on his adventure in pursuit of Medusa’s head. The winged helmet (which grants invisibility) is given to Perseus by Pluto.

43. See Lemprière, p.464-466, for the story of Perseus. Interestingly, it is Mercury who gives Perseus the winged sandals when Perseus is about to embark on his adventure in pursuit of Medusa’s head. The winged helmet (which grants invisibility) is given to Perseus by Pluto.

![]() 44. “The Perseus is an emblem of triumph. Perseus holds up by her snaky hair the decapitated head of Medusa, the horrifying gorgon whose gaze turned onlookers into stone. The hero’s ingenuity –avoiding her petrifying gaze by using his metal shield to reflect her image- allowed him to vanquish what had seemed an invincible threat to civilization.” Quoted from Sarah Blake McHam, “Public Sculpture in Renaissance Florence”, Looking at Italian Renaissance Sculpture, edited by Sarah Blake McHam, Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998, p.169.

44. “The Perseus is an emblem of triumph. Perseus holds up by her snaky hair the decapitated head of Medusa, the horrifying gorgon whose gaze turned onlookers into stone. The hero’s ingenuity –avoiding her petrifying gaze by using his metal shield to reflect her image- allowed him to vanquish what had seemed an invincible threat to civilization.” Quoted from Sarah Blake McHam, “Public Sculpture in Renaissance Florence”, Looking at Italian Renaissance Sculpture, edited by Sarah Blake McHam, Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge University Press, 1998, p.169.

![]() 45. For a summary of the history and interpretation of this painting see the entry in the exhibition catalogue by Flavio Caroli, l’Anima e il volto. Ritratto e fisiognomica da Leonardo a Bacon. Milan: Electa, 1998, p.182-183.

45. For a summary of the history and interpretation of this painting see the entry in the exhibition catalogue by Flavio Caroli, l’Anima e il volto. Ritratto e fisiognomica da Leonardo a Bacon. Milan: Electa, 1998, p.182-183.

![]() 46. Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. The Documents of 20th-Century Art. New York: Viking Press, 1976, p.72.

46. Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. The Documents of 20th-Century Art. New York: Viking Press, 1976, p.72.

![]() 47. Duchamp writes to Picabia from Monte Carlo: “it’s delicious monotony without the least emotion”. And to Doucet: “I’m beginning to play and the slowness of progress is more or less a test of patience. I’m staying about even or else am making time in a disturbing way for the aforementioned patience, but still doing that or something else… I’m neither ruined nor a millionaire and will never be either one or the other.” As summarized by Lebel: “He considers his martingale infallible in this respect but he also admits that if one perseveres long enough one can hope to win an amount equal to the wagers of a clerk who works in his office as many hours as the gambler does in the casino.”

47. Duchamp writes to Picabia from Monte Carlo: “it’s delicious monotony without the least emotion”. And to Doucet: “I’m beginning to play and the slowness of progress is more or less a test of patience. I’m staying about even or else am making time in a disturbing way for the aforementioned patience, but still doing that or something else… I’m neither ruined nor a millionaire and will never be either one or the other.” As summarized by Lebel: “He considers his martingale infallible in this respect but he also admits that if one perseveres long enough one can hope to win an amount equal to the wagers of a clerk who works in his office as many hours as the gambler does in the casino.”

![]() 48. A Duchampian game of words between equilibre and et qui libre? (Who is free?)

48. A Duchampian game of words between equilibre and et qui libre? (Who is free?)

![]() 50. Max Harrison, Poulenc, Les Mamelles de Tiresias. Le Bal Masqué.(CD brochure) Saito Kinen Orchestra, Seiji Osawa (456 504-2 Philips).

50. Max Harrison, Poulenc, Les Mamelles de Tiresias. Le Bal Masqué.(CD brochure) Saito Kinen Orchestra, Seiji Osawa (456 504-2 Philips).

![]() 51. See www.caduceus.co.uk

51. See www.caduceus.co.uk

©2003 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris. All rights reserved.