click to enlarge

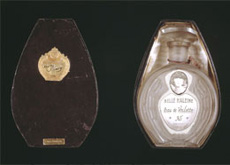

Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette

[Beautiful Breath: Veil Water], 1921

Assisted readymade: Rigaud perfume bottle

with label created by Duchamp and Man Ray,

bottle 6” (15.2 cm) high, in an oval,

violet-colored cardboard box,

6 7/8 x 4 7/8 inches (16.3 x 11.2 cm);

inscribed on gold label attached

to the back of the box:

Rrose / Sélavy / 1921

Belle Haleine: Eau de Voilette [Beautiful Breath: Veil Water] is the amusing title Marcel Duchamp gave to a work of art that he made—with the assistance of Man Ray—in the spring of 1921. At first glance, it appears to be little more than an ordinary perfume bottle, although readers of French might confuse it with a mouth wash, which, if consumed, would give them, as the label indicates, belle haleine [beautiful breath]. We now know that in order to produce this work, Duchamp appropriated an actual bottle of perfume issued by the Rigaud Company of Paris in 1915 for “Un air embaumé,” the name given to the most popular and best-selling fragrance the perfumery had produced in its sixty-five year history. Advertisements for this product feature a scantily clad female model holding a bottle of the perfume below her nostrils,

click to enlarge

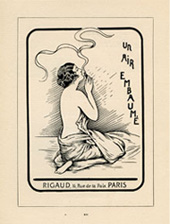

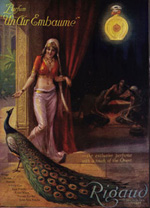

Figure 1

Advertisement for Un Air

Embaumé, Rigaud Perfume,

La Rire no. 88 (9 October 1920)

the essence of the liquid rendered visible as an undulating, ribbon-like shape floating through the air. The model is shown taking a deep breath, her eyes closed and head tilted slightly back, as if to suggest that the scent possess the qualities of an aphrodisiac, rendering powerless all who inhale its intoxicating vapors. It may have been precisely these qualities that attracted Duchamp to this particular brand of perfume, for he wished to draw attention to the woman whose features are depicted on the bottle, his newly introduced female alter-ego: Rose Sélavy.

Rose Sélavy was born by self-procreation in 1920. Duchamp—who was then living in New York and who, for years, had harbored a personal and professional disdain for entrenched, academic systems within the world of art—sought to establish an entirely new artistic identity. Just as he had invented the pseudonym of R. Mutt three years earlier (when, in 1917, he boldly submitted a white porcelain urinal to an art exhibition with infamous results), this time he wanted something more permanent, an alternative persona through which he could hide his true identity while continuing to function as an artist. “The first idea that came to me was to take a Jewish name,” he later explained. “I was Catholic, and it was a change to go from one religion to another! I didn’t find a Jewish name that I especially liked, or that tempted me, and suddenly I had an idea: why not change sex? It was much simpler. So the name Rrose Sélavy came from that.”1 The name Rose Sélavy not only succeeds in changing gender, but, to a somewhat lesser extent, the Jewish identity he originally desired. Sélavy is a close phonetic equivalent of Halévy, a common Jewish name in France. Moreover, in America the name Sélavy could be pronounced “Say Levy,” but of course the most obvious pun is with the French phrase “c’est la vie” [that’s life].2 Almost immediately, Rose was credited with the production of works of art, such as Duchamp’s Fresh Widow—a miniature French window with its panes covered by black leather (Museum of Modern Art, New York)—which, on its support, is inscribed in bold uppercase letters: “COPYRIGHT ROSE SELAVY 1920.”

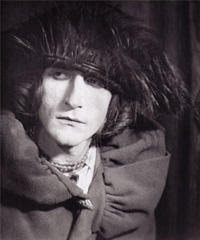

Although Rose Sélavy was already functioning as an artist, it was not until the winter of 1920-21 that Duchamp decided that she should become visibly manifest, so he enlisted the services of his friend and colleague Man Ray to help take pictures of himself in drag.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Man Ray, Portrait of Rose Sé

lavy, 1921, New York, negative Estate

of Man Ray, Musée National d’Art

Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou,

Paris copy print from Jean-Hubert Martin,

Man Ray Photographs [London:

Thames & Hudson, 1981]))

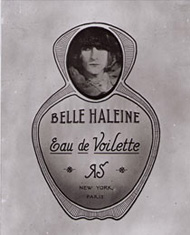

He printed one of the pictures he had taken of Rose Sélavy and closely cropped the head into an ovoid format, which he placed atop a symmetrical design in black ink meant to fit within the wing-like, decorative shapes that emanate from the base of the Rigaud perfume bottle. He then carefully wrote the word BELLE in ascending letters on the left side of the label, followed by the word HALEINE descending on the right. Below that, he wrote Eau de Voilette in an expressive italic font, underneath which appear the letters “RS,” the initials of Rose Sélavy (the “R” rendered backwards, its lower branch responding to the flourish given to the seraph atop of the letter “S”). At the base of the label appears the locations where, presumably, the perfume would be sold—New York and Paris—two city centers that Duchamp traversed frequently during these years (indeed, he probably purchased the bottle during a trip to Paris in 1919). A photograph of the layout was reduced in size to fit the small format of the perfume bottle, whereupon the resultant print was then carefully glued to its surface. The finished product made its first public appearance on the cover of New York Dada, a single-issue magazine edited by Duchamp and Man Ray that was released in April 1921.

click to enlarge

Figure 3

Man Ray, Label for the Belle

Haleine, 1921, gelatin silver

print, 8 13/16 x 7 inches (The J. Paul

Getty Museum, Los Angeles).

The bottle was placed in the center of the cover and surrounded by a seemingly endless repetition of the type-written words “new york dada april 1921” printed in lower-case letters and positioned upside-down in an exceptionally small font that ran to the edges of the cover, the whole cast, appropriately, in a reddish, rose-colored hue.

Exactly whose idea it was to reproduce this bottle on the cover of New York Dada is unknown, but we do know that, at the time, both Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp had hoped that the Dada movement—which had originated in Europe and spread quickly throughout various European capitals—would continue to broaden its scope internationally. In a metaphorical sense, then, the artists may have equated the ability of a fragrance to permeate its surroundings with the convention-defying capabilities of Dada to influence all the arts. Unfortunately, however, at the time the Dada movement was in the process of breathing its last breath, for within a matter of years, it would be replaced by Surrealism in Paris, while the artists in New York either left for Europe or retreated to more conventional forms of artistic expression. The seed of Dada would eventually germinate, but only about a half century later, when a group of young artists in London, New York and Paris became aware of Duchamp’s work—particularly the readymades—and immediately recognized its radical aesthetic implications. Ironically, this scenario reinforces a possible alternate reading to the words “un air embaumé,” which translates literally as “perfumed air,” but which, in English, could also be read as “embalmed air.” Indeed, it has recently been observed that the box in which the perfume was packaged—which was preserved and is intended to be part of the final work of art—is curiously shaped like a coffin.3 Like a mummy enwrapped in cloth and preserved for eternity, it would seem that today—with the artist’s uncontested influence on the development of contemporary art—Duchamp’s bottle of perfume has finally been opened, allowing for the diffusion of an alluring spirit that virtually everyone can now readily detect.

click to enlarge

Figure 4

New York Dada,

April 1921, cover. Private

Collection, New York

Rigaud was the perfect fragrance for Duchamp to have selected. Not only was it a known and popular French brand of perfume, but its exotic qualities—which the firm emphasized in all of its advertisements—was an ideal fragrance for the somewhat vulgar and lascivious Rrose to endorse. In an advertisement that appeared in Harper’s Monthly, it is implied that Un Air Embaumé was a scent that originated in an unspecified Arab country located somewhere in the Middle East; it depicts a harem girl gesturing toward a peacock with one hand, while she uses the other hand to hold back a curtain revealing the interior of a darkened boudoir.

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Advertisement for Un Air Embaumé,

Rigaud Perfume Company,

Harpers Monthly, December

1919. Collection Francis M.

Naumann, New York

There, a couple inclines on a bed, while a gold bottle of Rigaud floats mysteriously above their heads, glowing in the darkness like an apparition. Another advertisement that appeared in several American fashion magazines shows a woman seated in her dressing room, visible to viewers through an open curtain door.

“A peep into the boudoir of any much sought-after woman,” the caption reads, “will usually reveal some RIGAUD odeur as the real secret of her power to fascinate men.” In small print at the bottom of the page, the advertisement informs prospective buyers that, if purchased for yourself or as a gift, the fragrance is assured to have an enduring effect. “Un air embaumé is one of the most loved of Rigaud odeurs. It is the type of rare fragrance that a woman clings to devotedly for many, many years.”

click to enlarge

Figure 6

Advertisement for Rigaud

Perfume, New York fashion

magazine, ca. 1920-21. Collection

Douglas Vogel, New York

In June of 1921—a few months after the appearance of New York Dada—Duchamp returned to Paris, where, later in the year, he signed a large painting by Picabia entitled L’Oeil cacodylate (Musée National d’Art Moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris) with the name Rrose Sélavy, spelling the name Rrose for the first time with a double-r. Later he said that this was required, for, as he explained, “the word ‘arrose’ demands two R’s.”4 Clearly Duchamp intended to evoke a pun on the word “eros,” for Rrose Sélavy is a homonym for the phrase “eros c’est la vie” [eros, that’s life]. Although less often acknowledged, the double-r might also have been derived from the French verb arroser, which means to wet or moisten, an appropriate word considering the obviously erotic connotations of perfume, which the manufacturer wanted users to think offered one of the first elements of attraction in any successful amorous encounter. Duchamp later signed the box of his perfume bottle with the name Rrose Sélavy (using the double-r), and gave it to Yvonne Chastel-Crotti, the ex-wife of his former studio-mate in New York, Jean Crotti (a Swiss-born painter who had married Duchamp’s sister Suzanne), a woman with whom Duchamp had had his own brief amorous encounter in 1918.5

The bottle remained in Yvonne Crotti’s possession throughout her life, and although it had been included in a group show of collage in Paris in 1930, it was shown for the first time within the context of Duchamp’s work in an exhibition organized by the Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery in New York in 1965.6 It was there that the object was first identified as an “assisted readymade,” indicating that—as with all other readymades—the object itself already existed, but required some alteration, that is to say, assistance on Duchamp’s part in order to bring it into being as a work of art. That assistance resulted in having created one of the most provocative works of art ever made, a simple bottle of perfume whose liquid long ago evaporated, but whose essence, to be sure, will continue to influence artists long into the future.

This text was first published as the entry on Duchamp’s Belle Haleine: Eau de violette in the sales catalogue Collection Yves Saint Laurent et Pierre Bergé, Christie’s Paris, 23 February 2009, lot no. 37.

Notes:

1 Pierre Cabanne, Interview with Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. by Ron Padgett (New York: Viking Press, 1971), p. 64.

2 The similarity to Halévy was pointed out by Ellen Landau, and is reported in Bradley Bailey, Duchamp’s Chess Identity, doctoral dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 2004, n28, p. 107; see also Bradley Bailey, ” Rrose of Washington Square: Marcel Duchamp, Fanny Brice, and the Jewish Origins of Rrose Sélavy ,” Source XXVII, no. 1 (Fall 2007), p. 41.

3 As suggested by Rhonda Roland Shearer in Bonnie Jean Garner, “Duchamp Bottles Belle Greene: Just Desserts for his Canning,” Tout-Fait, issue 2 (2000): www.toutfait.com. For the double reading of the title, see also Steven Jay Gould’s contribution to this article: “From the Bitter Negro Pun to the Beautiful Breath Bottle.”

4 Cabanne, Dialogues with Duchamp, p. 65.

5 Arturo Schwarz claims that this work was “signed after 1945,” although he provides no explanation for why the signature was applied at this time (see Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp , 3rd revised and expanded edition [New York: Delano Greenidge, 1997], vol. II, cat. no. 388, p. 688).

6 NOT SEEN and/or LESS SEEN of/by MARCEL DUCHAMP/RROSE SELAVY 1904-64, Cordier & Ekstrom, Inc., New York, 14 January – 13 February 1965, cat. no. 71. At the time of this show, Yvonne Crotti was living in London (her last name changed by married to Lyon), and it was probably through Duchamp’s assistance that the work was sold (at the time, Arne Ekstrom, proprietor of the gallery, was actively acquiring works by Duchamp for the Mary Sisler Collection). The 1930 show that included his Belle Haleine / Eau de Violette was Exposition de Collages, organized by Louis Aragon for the Galerie Goemans, Paris, March 1930; Duchamp was also represented by Pharmacy, an example of The Monte Carlo Bond, and two versions of the L.H.O.O.Q.(see Jennifer Gough-Cooper and Jacques Caumont, “Ephemerides on and about Marcel Duchamp and Rrose Sélavy 1887-1968,” in Pontus Hulten, ed., Marcel Duchamp, exh. cat., Palazzo Grassi, Venice, 1993, entry for 02/06/1930).