In 1983, three works by Marcel Duchamp found their way into the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa (Te Papa, Wellington, New Zealand). The following account demonstrates how two New York-based friends of Duchamp, Judge Julius Isaacs, and Betty Isaacs (Fig. 1) are tied to this course of events.

click to enlarge

Figure 1

Betty Isaacs and Julius

Isaacs, Wellington New Zealand,

1966. Copyright Fairfax NZ

Ltd. Courtesy Dominion

Post and Te Papa Museum

Moreover this essay exposes how this process, despite the diligence of Duchamp scholarship, led to the virtual disappearance of these works from the record. This essay will also draw (preliminary) conclusions about the significance of this process, both in terms of the new light shed on the fate of Duchamp’s work, and of the reception of this work outside the centers of art practice.(1) These works are the BETTY waistcoat (1961, New York), The Box in a Valise, (Edition D. 1961, Paris) and The Chess Players (copperplate etching, artist’s proof, 1965, New York). In addition, five 1st edition publications on Marcel Duchamp signed with personal dedications accompany the works.(2) All these form part of the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand (NAG) in 1983.

The Duchamp works are the most important items in a gift of over 200 artworks, publications, and articles donated to the museum by the estate of Mrs. Betty and Judge Julius Isaacs, who were New York-based friends of Marcel Duchamp. The bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs, as characterized by Betty Isaacs, born in Tasmania, Australia and a one-time New Zealand resident between 1886 and 1913, is an eclectic range of over 80 sculptures, of both carved and cast forms. These were made during Isaacs’ career as a sculptor after graduating from the Cooper Union Art School in 1928. The bequest also contains 45 amateur paintings by Julius Isaacs, a small grouping of artworks by the American artist Larry Rivers, and works by two important New Zealand expatriates Frances Hodgkins (NZ/London) and Billy Apple (NZ/London/New York). The bequest also originally contained a large number of books which found their way into the NAG or other Wellington libraries, or, deemed to be of little value, were otherwise thrown into the rubbish bin.

Duchamp’s works stand out in relation to the rest, as the entire Bequest was accepted on the basis of the Duchamp articles, as well as the biographical association Betty Isaacs has with New Zealand. This was a clear sign of the museum’s recognition of Marcel Duchamp’s significance and their desire to acquire such works for their collection. History would demonstrate that this was an astute and canny move, as unique works by Duchamp were rarely available or in art market circles.(3) Such rarity has caused consternation for those wishing to collect works by the artist who has eclipsed other 20th Century figures as holding the central importance to the history of contemporary art.

click to enlarge

Figure 2

Marcel Duchamp,

Boîte-en-valise

series G, 1968

Of the various artworks by Duchamp in the bequest, the following can be recorded. The Box in a Valise (Fig. 2) contains 68 unnumbered items enclosed in a light-green cloth and signed by Marcel Duchamp in blue ball-point pen, characteristic of the edition of 30 boxes assembled by Jacqueline Matisse Monnier in Paris, 1961.(4) While this may have been a gift directly from Duchamp, no dedication appears within it. However, the Chess Players (Fig. 3) is indeed a gift from Duchamp to the Isaacs. It is an unnumbered artist’s proof, inscribed on the lower left in pencil ‘epreuve d’artiste,’ dedicated ‘pour Betty and Jules Isaacs’ in pencil on the lower centre, and signed and dated in pencil on the lower right ‘Marcel Duchamp/1965.’ This print belongs to a series of etchings engraved after Duchamp’s charcoal drawing, Study for Portrait of Chess Players (1911) (Fig. 4). The first series of etchings were a limited edition of 50 proofs, printed in black on handmade paper and hand numbered 1/50-50/50; plus ten artist’s proofs (one of which was a gift to the Isaacs).(5) A single print from this edition was given to each of the artists who had contributed to the group exhibition A Homage a Caïssa. This exhibition was arranged by Duchamp in which works by selected artists were sold for the benefit of the Marcel Duchamp Fund of American Chess.

click images to enlarge

- Figure 3

- Figure 4

- Marcel Duchamp, The

Chess Players, 1965 - Marcel Duchamp, Study

for Portrait of Chess

Players, 1911

click to enlarge

Figure 5

Marcel Duchamp, Betty

Waistcoat, 1961. Bequest

of Judge Julius Isaacs,

New York (1983). Collection

of the Museum of New

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

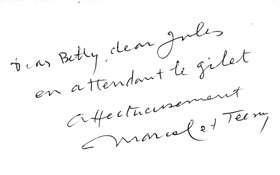

The BETTY waistcoat (Fig. 5) is signed ‘Marcel Duchamp/1961’ in blue ball-point pen on the inside lining. Belonging to the series “Made to Measure” (1957-1961), this modified readymade is catalogued by Arturo Schwarz in The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp as ‘present location unknown’. Schwarz writes, “Duchamp designed this waistcoat for Isaacs, a New York jurist and close friend (The occasion of the gift is unknown)”.(6) The BETTY waistcoat is another instance of Duchamp’s habit to sign works and then to send these works to his peers, friends, or family. Three out of the four waistcoats from the series, “Made to Measure,” were gifts: the TEENY waistcoat (Fig. 6) was a gift from Duchamp to his wife in 1957, and the SALLY waistcoat (Fig. 7) was a gift to his son-in-law Paul Matisse on the occasion of his marriage to Sarah “Sally” Barrett on December 27, 1958. The fourth, the PERET waistcoat (Fig. 8), was named after Duchamp’s friend Benjamin Péret.(7) The BETTY waistcoat was in all likelihood presented as a gift to the Isaacs for their 40th wedding anniversary (celebrated on September 11 1961). In a 1st edition copy of Richard Hamilton’s typographic translation The Bride Stripped Bare and Her Bachelors, Even (1960), gifted to the Isaacs, Duchamp pens: “dear Betty, dear Jules en attendant le gilet, affectueusement Marcel et Teeny” (Fig. 9) – here is a short correspondence setting up an exchange in the production of the work of art, one that demonstrates the awareness Marcel and Teeny would have had of the Isaacs’ forthcoming wedding anniversary. This is backed in 1967 when Duchamp penned a dedication to the long union of the judge and the sculptress: theirs was “an amicable institution.” (Fig. 10)

click images to enlarge

- Marcel Duchamp,

Teeny Waistcoat, 1957 - Marcel Duchamp,

Sally Waistcoat, 1958 - Marcel Duchamp, Peret

Waistcoat, 1958

click images to enlarge

- Page from The Bride Stripped Bare

by Her Bachelors, Even (1960),

Richard Hamilton. Collection of the

Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongawera - Page from The World of Marcel Duchamp,

187-, Calvin Tomkins inscribed by Marcel

Duchamp: “pour Betty et Judge Isaacs/an amicable

Institution/et affectueusement/Marcel Duchamp/1967.”

Collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

click to enlarge

Figure 11

Marcel Duchamp, Couple

of Laundress’s

Aprons, 1959

A waistcoat, ‘made to measure’ through tailoring, recalls Duchamp’s earliest thought for the term ‘readymade’ as an article of clothing available and ready to wear. A waistcoat, when worn, constitutes a union of sorts to the body. Through linguistic ploy, the letters B. E. T. T. Y (spelled in a 24-point lead font) are individually affixed to the waistcoat as buttons, and spell the name of Julius Isaacs’ wife in mirror reverse. By threading buttons Isaacs joins with his wife, a union that evokes an erotic connotation – “considering the fact that Duchamp’s most celebrated work is based on the theme of a bride being stripped bare, any piece of wearing apparel used in his art could carry the potential for a more erotic meaning”.(8) Waistcoats were not the only garments used by Duchamp at this time; during the same period that the waistcoats were made for the series “Made to Measure” (1957-61), Duchamp also made the Couple of Laundress’s Aprons (1959, Paris) (Fig. 11), which are erotic garments of clothing of another (gendered) sort: domestic, not suited attire.

Betty Isaacs, forming the first-hand link to New Zealand, is the principal connection behind the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs and New Zealand’s National Art Gallery. Betty Isaacs was born Ettie Lewis on September 2, 1894 in Hobart, Tasmania, and died aged 76 on February 4, 1971 in New York. She was one of four children to Annie Lewis (nee Cohen) a New Zealander, and Henry Lewis an Australian, who were married in Hobart in 1882. Upon the death of Henry Lewis in 1886, the Lewis family (Annie and children Gabriel, Rachel, Ettie and Rosalie) were brought by Betty’s grandparents, Mr. and Mrs. Benjamin Cohen, to Wellington, New Zealand where Betty was educated. Betty’s mother married a second time to Maurice Ziman on January 27, 1896 and together began a new family, eventually producing three children. In 1902, the family traveled to London and New York, returned to Wellington in 1903, and soon thereafter suffered a tragic setback: the death of Betty’s youngest sister Rosalie in 1905, and Betty’s 49 year old mother Annie Lewis in 1906. Betty remained in New Zealand for seven years, completed her education, and then, at age 19, departed for New York in 1913.(9)

Upon arriving in New York, Betty Isaacs changed her name and reverted back to her original family name Lewis. She trained and then served as a librarian between the years of 1915 and 1918. She then, for a period, worked at the New York City Public library where she met Julius Isaacs. They married on September 11, 1921. Between the years of 1925 and 1928 Betty Isaacs trained at the Cooper Union Art School and emerged as a sculptor in the late 1930’s after working as a designer in the textiles industry. Betty Isaacs’ debut exhibition was in 1953 at the Hacker Gallery, New York, and included 38 items of sculpture, 5 ceramic pictures and 2 mosaic panel drawings. The exhibition drew varied reviews from the New York Times staff critics: “Betty Lewis Isaacs . . . devotes herself to portraying animals from fish to polar bears, and she has evolved a manner of representing them that is naturalistic without being photographic”.(10) But one critic found that “her animals tend to be petty,” instead favoring: “an inscrutable, poetic “Girl’s Head” just a little in the Zorach vein”.(11) Isaacs worked with a range of materials including wood, stone, alabaster and bronze. She was an enthusiast of wood in particular, and on a 1966 return trip to New Zealand hoped to find examples of carvings in the native Totara and Kauri.(12)

It was Betty Isaacs’ fond remembrance of her time spent in New Zealand that drew her and Julius Isaacs back to visit between August 25 and September 15, 1966. These memories are evident in the poem written by John Cage that recalls Isaacs’ early pastimes living in the suburbs of Wellington. In Number 66 of his many one minute read aloud stories published in Silence (1961) and A Year to Remember (1968), Cage writes:

Betty Isaacs told me that when she was in New Zealand she was informed that none of the mushrooms growing wild there were poisonous.So one day when she noticed a hillside covered with fungi,she gathered a lot and made catsup.When she finished the catsup, she tasted it and it was awful.Nevertheless she bottled it and put it up on a high shelf.A year later she was housecleaning and discovered the catsup,which she had forgotten about.She was on the point of throwing it away.But before doing this she tasted it.It had changed color.Originally a dirty gray, it had become black, and, as she told me, it was divine, improving the flavor of whatever it touched.(13)

John Cage was a friend of Betty Isaacs who he would have met sometime after 1941 in the close neighborhood of Greenwich Village. Cage wrote about Betty Isaacs as a subject for the above story and one other, and forms the connection to the Duchamps during the period he built a closer friendship with Marcel and Teeny Duchamp in the early 1960s in Greenwich Village. He would have introduced the Isaacs who lived at 21 East 10th Street in the years between 1941 and Julius Isaacs’ death in 1979, near the Duchamp’s 28 West 10th Street apartment. Prior to Marcel and Teeny’s departure from New York in 1964, Cage often visited the Duchamps at their apartment. In an interview with Calvin Tomkins, John Cage commented, “I was living in the country then, and I would bring wild mushrooms I had gathered and a bottle of wine, and Teeny would cook dinner.”(14) It is highly probable that Betty Isaacs would share stories of New Zealand over a dinner of mushrooms, in the company of her husband Julius, John Cage and Marcel and Teeny Duchamp. The relationship Marcel and Teeny Duchamp had with the Isaacs does not feature significantly in published literature. Judge Julius Isaacs was a patron of the arts, particularly of music and writing, and according to Arturo Schwarz, a “close friend” of Marcel Duchamp.(15) Julius Isaacs was born in 1896 and died in New York on his 83rd birthday on December 31, 1979. After studying at the City College, City University of New York where he was valedictorian and class president in 1917, he trained in law and his public service began in 1934. During the 1940’s he became Acting Corporation Counsel of the City of New York and was appointed as a New York City Magistrate by Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia. Julius Isaacs may well have been acquainted to Duchamp through legal practice or through social circles of New York arts patrons. Little extant correspondence (if any) between the Isaacs and Duchamp’s still remains.(16) Betty Isaacs and Judge Julius Isaacs did not have any children, and Betty’s surviving family members in New Zealand are found on Betty’s stepfather’s side, Maurice Ziman, who, while remembering meeting the Isaacs on their 1966 New Zealand visit, have no knowledge of the extent of their New York based lifestyle or their friendships that developed in the 1960s.

click to enlarge

Figure 12

Page from Marcel Duchamp

(1959), Robert Lebel

(translated by George Heard

Hamilton). Collection of

the Museum of New Zealand

Te Papa Tongarewa.

The nature of the Duchamp/Isaacs friendship is verified by four short personal inscriptions written by Duchamp in publications gifted to the Isaacs, now in Te Papa’s works on paper collection. Dating from 1959 with the publication of Robert Lebel’s Sur Marcel Duchamp in English (translated by George Heard Hamilton) these read: “pour Betty, pour Jules Isaacs le magician des portes qui, pour lui, ne sout jamais ni ourestes . . . en grande affection, Marcel Duchamp N.Y. Oct. 1959.”(Fig. 12) Secondly, the aforementioned dedication in Richard Hamilton’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1960): “dear Betty, dear Jules en attendant le gilet, affectueusement Marcel et Teeny”. On the inside cover to the catalogue NOT SEEN and/or LESS SEEN of/by MARCEL DUCHAMP/RROSE SELAVY 1904-64 (Cordier & Ekstrom Gallery, N.Y., 1965) Duchamp scribed: “To the judge of all things, dear Jules and Betty. Marcel.” And, as also previously noted, in Calvin Tomkins’ The World of Marcel Duchamp 1887 – (1966): “pour Betty et Judge Isaacs, an amicable Institution, et affectueusement. Marcel Duchamp, 1967.” One can conclude that their friendship was based through contact in Greenwich Village after 1941, and that these were also strengthened by John Cage’s friendship with Betty Isaacs. The ‘BETTY’ waistcoat and the personal dedications stand as proof, and from these are gleaned certain insight into the nature of their friendship.

Fondness for New Zealand was shared by both Betty and Julius Isaacs. On occasion, they dined and entertained the Minister of New Zealand’s foreign affairs, and over the years entertained other notable New Zealanders at their New York home: including Paul Gabites and Richard Taylor (New Zealand Consular-Generals), Sir Thaddeus McCarthy (Judge and president of the New Zealand Court of Appeal), John Hopkins (symphony conductor and co-founder of the New Zealand National Youth Choir) and the New Zealand expatriate artist Douglas MacDiarmid.(17) Their bequest contains works by two of New Zealand’s most significant expatriate artists, Frances Hodgkins (NZ/London) and Billy Apple (NZ/London/New York). In addition, on June 1966, Julius Isaacs managed an exhibition of an important New Zealand expatriate, the writer and novelist Katherine Mansfield, for the 34th annual International Congress of the P.E.N. Club entitled “The Writer as Independent Spirit”.(18) Shortly after this congress, the Isaacs embarked on their New Zealand visit.

The Isaacs’ relationships with the New Zealand Consulate in New York underpin connections established for Betty Isaacs’ work in the NAG in New Zealand. Paul Gabites’ efforts (through photographs) to bring her work to the attention of the Selection Committee of the NAG in 1964, was met with “great interest.” However, the Selection Committee’s reply to Paul Gabites in 1964 also informed him that two purchases, a Barbara Hepworth and a Derain oil painting, had “more than absorbed our import collection for the next two years!” They added that “the members, however, have been made aware of the work of Betty Isaacs and we are that much ahead”.(19) It was after Betty Isaacs’ death in 1971 that Julius Isaacs, with increased energies, offered her works to the NAG, which ultimately formed further origin for the later bequest. In 1972, nearly one year after Betty Isaacs’ death, Julius Isaacs wrote to Melvin Day, the director of the NAG, outlining brief biographical details of his wife Betty Isaacs. Two years later, the Selection Committee agreed to accept one work by Betty Isaacs, a gift sent from Julius Isaacs. In 1974, New Zealand’s Minister of Overseas Trade, Mr. Walding, accepted as ‘a gift to the Government and people of New Zealand’ the abstract sculpture “Torso in Bronze” (1962, New York). This transaction forms a definite trace to the bequest later confirmed in 1981 to the NAG by the executors of Judge Julius Isaacs’ estate.

Instruction left in Julius Isaac’s will asked the executors of his estate (representatives of the Chemical Bank Corporation, New York) to determine a suitable repository for the collection of his art works and related items either in the United States or abroad.(20) Isaacs’ will, dated August 29 1979, reads under paragraph (U) of Article Second: “I give and bequeath all my books and art objects, including paintings, sculpture and drawings to such museums and libraries in this country, Israel and New Zealand, as my executor shall select, to be kept as intact as possible or distributed separately to various such institutions, to be known as the BETTY LEWIS ISAACS and JULIUS ISAACS COLLECTION or COLLECTIONS . . . . I urge my executor to follow the advice of MEYER SHAPIRO and DOROTHY MILLAR as to the proper allocation of these works of art, especially of the sculpture of BETTY LEWIS ISAACS so that her reputation as an artist may best be preserved.”(21)

The initial offer of the estate’s collection was sent by L. David Clark (representative executor) to the Secretary of the Art Galleries and Museums Association of New Zealand (AGMANZ) on 13 November 1980. Luit Bieringa, who was the vice-president of AGMANZ and director of the NAG, does not recollect the broad possible scope of benefactors for the bequest. Bieringa’s opportunity to view objects, works and books in the estate became the opportunity “to not miss out on something unique” making sure that “the sequence from Betty Isaacs and the Judge Julius Isaacs bequest to the National Gallery was a natural one”.(22) Furthermore, the trace of origins outlined in this article certainly support Bieringa’s claim and would have determined the executor’s decision.

click to enlarge

Figure 13

Telegram from Chemical Bank

Corporation (N.Y) to the NAG.

Postmarked 06 June 1981,

Wellington, New Zealand.

Archives of the Museum of New

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

It was Bieringa who secured the bequest for New Zealand. With AGMANZ support, Bieringa entered into a protracted process of disposition and scheduled a meeting with Paul F. Feilzer, the Senior Trust Officer of Chemical Bank Corporation, for February 8 and 9 1981 in New York, when he viewed selected works in the bequest. The collection of artworks and other related items in the Isaacs estate had been appraised by William Doyle Galleries, Inc., New York, who appraised (in U.S. dollars) the Betty Waistcoat at $20,000.00; the Chess Players at $2,000.00 and the Box in a Valise at $3,000.00. The bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs was confirmed via telegram to Luit Bieringa on June 6, 1981 from the Chemical Bank Corporation (Fig. 13), and the Board of Trustees of the National Art Gallery voted unanimously to approve acquisition on June 11, 1981. Although this approval was passed in June 1981, and Bieringa personally signed the receipt and release of the bequest in New York on November 9, 1981, it took until February 1983 before the works were formally accessioned into the national collection.

click to enlarge

Figure 14

Inventory of the Bequest

of Judge Julius Isaacs,

shipped by Day & Meyer,

Murray & Young Corp. –

Packers, Shippers and Movers of

High Grade Household Effects and

Art Objects (N.Y.) (23 November 1981).

Archives of the Museum of New

Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

Delays are not an uncommon occurrence a propos a peripheral location. The news of obtaining the bequest originally in June 1981 was in fact new news again by the time of its actual arrival in Wellington and its formal acquisition in 1983. The delay was due to the distance the freighted works had to travel across the Pacific Ocean (and also due in part to the large size of the entire bequest). The total freight was comparatively expensive (estimated at $5,700.00 US dollars), yet approval of the bequest was conditional on NAG’s meeting associated costs for its climate-controlled freight to New Zealand. The full inventory of the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs was shipped by Day & Meyer, Murray & Young Corp. — Packers, Shippers and Movers of High Grade Household Effects and Art Objects (Fig. 14), and departed New York on the Malmros Monsoon on November 23, 1981, arriving in New Zealand on December 18, 1981 through Auckland. The shipment reached its final destination at the National Art Gallery in Wellington in February 1982. It took another full year for formal acquisition processes to be completed, but, finally, ‘Duchamp’ had arrived in New Zealand.(23)

Bieringa, delighted by the acquisition of Duchamp’s works, writes: “As a young country New Zealand cannot, apart from its superb indigenous cultural assets, boast of rich assets reflecting the art historical developments of the Western world. As such several of the works contained in the Isaacs Estate, in particular the Duchamp items, will have a significant impact with the art museum collections in New Zealand, whereas their retention in Europe and America will only marginally affect the stature of any significant collection. Given the limited financial resources of our museums the impact of the Isaacs collection will be substantial.”(24)

While the bequest was somewhat serendipitous, Bieringa exhibited a presence of mind in securing a small but significant collection of Duchampian works and articles for the NAG, especially at a time contemporaneous to a wider desire in collecting works by Duchamp. The bequest belongs to a limited transfer of his works to international museum collections after the artist’s death. Museums and curators arrived at the significance of Duchamp’s work much later than that of other 1960’s New York based artists, and so a period of institutional interest in Duchamp’s work grew belatedly.(25) Within a period in which very few Duchamp works might have actually been purchased or exchanged, the National Art Gallery of New Zealand succeeded in obtaining a small but unique collection.

Bieringa’s enthusiasm for the transaction made in 1983 has not been sustained by the institution that had facilitated the bequest. Indeed, The Box in a Valise, documented on its acquisition, has been shown on two occasions: at the Auckland Art Gallery, for the exhibition ‘Chance and Change’ in 1985, and more recently in 2003 at the Te Papa Museum, in ‘Past Presents’ an exhibition of works focusing on gifts to the collection. The BETTY waistcoat and The Chess Players were also documented upon their acquisition, but Te Papa museum art catalogue files have not recorded any further movement of these items for exhibition, either within the institution or beyond. In addition, the 80 sculptural works by Betty Isaacs have never had any comprehensive exhibition, and remain in their brown cardboard boxes in storage. Duchamp’s works have never formed a collective basis for any exhibition in New Zealand, though such an exhibition is long overdue. Therefore, akin to one of Duchamp’s time based pleasures (from his delayed work on the Large Glass) these three Duchamp works have, as in that figure of speech, attracted dust.

So what can be made of the fate of these Duchampian artworks? Firstly, their disappearance into a Museum Collection in a small city in an isolated country at the “bottom” of the South Pacific has effectively meant they were lost (until now) to Duchamp scholars. This fact starkly reminds us of New Zealand’s peripheral situation vis-à-vis the centres of culture and for which delays are a particular and peculiar circumstance. Yet, delay is also a favored operation and strategy of Marcel Duchamp and the sequential ‘delays’ to the uptake of Duchamp’s work in the 20th Century suggests that the marginal geographical location where these three Duchamp works are located is an affirmation of the ubiquity of their maker. These facts only impresses a stronger urge to make some sense out of these works within the cultural context in which they reside, in relation to the wider operations and strategies of Marcel Duchamp’s work. Rather than simply celebrate their re-discovery, I would argue the fate of these works actually tallies with aspects of Duchamp’s practice and this approach would stitch the works back into the picture.

click to enlarge

Figure 15

Marcel Duchamp as

Rrose Sélavy,

1921, photographed by Man

Ray, retouched by Duchamp

In attributing ubiquity one might think of Duchamp’s demeanor, his trans-gendered performance as Rrose Sélavy (Fig. 15), his employed translation and turns in meaning between French and English, his personal history and status as an expatriate between Paris and New York, travelling and slipping between varying reputations on both sides of the Atlantic. It is Duchamp’s ability to resist classification, at variance to other 20th century artists, that spawned a highly mobile legacy across historical periods and across generations of art makers. It is here that register is found with the Isaacs’ bequest: not for the first time material and visual artifacts by Duchamp’s hand slipped across national borders, arriving in a new context. The Isaacs’ bequest is part of a navigation of ‘Duchamp’ beyond the cultural centers within which he had historically operated. Marcel Duchamp’s legacy functions in the New Zealand context, as elsewhere, as an inescapable and indispensable example for local artists, but who have developed their distinctive practices not only as faint echoes of mainstream models but as canny adaptations within the limits of a local situation.

Returning to the dedications by Duchamp to the Isaacs, the earliest of which was signed by Duchamp in 1959, and the last in 1967, it is within this period that Duchamp was somewhat of a traveling inscriber: a (supposedly) retired artist, pen in hand, authorizing and laying claim to various reproductions of his work. “The sixties are notably the replica years – replicas of his own work, made by others and signed by Duchamp”.(26) Here the works in the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs (1983) offer a vital model to a culture that has historically relied on the reproducibility of art and the beneficiates of “friends” to participate in wider culture. New Zealand’s position in the history of art is necessarily replete with (international) comings and goings: replete with networks formed overseas, of generating acquaintances, friendships and unions to serve as contacts and to sustain lines of communication upon returning. It is befitting that gifts from Duchamp are, in turn, gifts to New Zealand’s National Museum, made under the auspices of friends of this country.

1. This research is ongoing. I would like to acknowledge Christina Barton (Art History, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand) for considerable support in writing this article and her teachings.

1. This research is ongoing. I would like to acknowledge Christina Barton (Art History, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand) for considerable support in writing this article and her teachings.

2. A complete list and the Written dedications appear later in this article.

2. A complete list and the Written dedications appear later in this article.

3. Francis M. Naumann discusses Duchamp’s relation to the art market at length in “Duchampiana II: Money Is No Object,” Art in America (March 2003): 67-73, and in “Marcel Duchamp: Money Is No Object. The Art of Defying the Art Market,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 2.5 (2003): News.

3. Francis M. Naumann discusses Duchamp’s relation to the art market at length in “Duchampiana II: Money Is No Object,” Art in America (March 2003): 67-73, and in “Marcel Duchamp: Money Is No Object. The Art of Defying the Art Market,” Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 2.5 (2003): News.

4. Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2000) 764.

4. Arturo Schwarz, The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp (New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2000) 764.

8. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk, eds., Affectionately Marcel – The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000) 187.

8. Francis M. Naumann and Hector Obalk, eds., Affectionately Marcel – The Selected Correspondence of Marcel Duchamp. (London: Thames and Hudson, 2000) 187.

9. Biographical details have been established through Julius Isaacs’ Letter to Melvin Day (10 Oct. 1972) and with descendents of Betty Isaacs: in email correspondence with Rob Golblatt “Betty Isaacs,” E-mail to the author (17 April 2005), and in personal interview with David Heinemann (30 May 2005).

9. Biographical details have been established through Julius Isaacs’ Letter to Melvin Day (10 Oct. 1972) and with descendents of Betty Isaacs: in email correspondence with Rob Golblatt “Betty Isaacs,” E-mail to the author (17 April 2005), and in personal interview with David Heinemann (30 May 2005).

10. “Isaacs Debut Show,” New York Times (12 Dec. 1953): 23.

10. “Isaacs Debut Show,” New York Times (12 Dec. 1953): 23.

11. “Women Sculptors at Galleries Here,” New York Times (12 Dec. 1953): 23.

11. “Women Sculptors at Galleries Here,” New York Times (12 Dec. 1953): 23.

12. “Sculptress Spent Childhood in New Zealand,” The Evening Star [Dunedin] (9 September 1966): page number unknown.

12. “Sculptress Spent Childhood in New Zealand,” The Evening Star [Dunedin] (9 September 1966): page number unknown.

13. John Cage. “Untitled” poem, cited at http://www.lcdf.org/indeterminacy/s.cgi?66 (20 April 2005). Thanks to Rob Goldblatt who in an idle moment stumbled upon this poem whilst searching the web for Betty Lewis.

13. John Cage. “Untitled” poem, cited at http://www.lcdf.org/indeterminacy/s.cgi?66 (20 April 2005). Thanks to Rob Goldblatt who in an idle moment stumbled upon this poem whilst searching the web for Betty Lewis.

14. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp – a Biography. (London: Pimlico, 1998) 411.

14. Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp – a Biography. (London: Pimlico, 1998) 411.

15. Julius Isaacs, Letter to Melvin Day (10 October 1972).

15. Julius Isaacs, Letter to Melvin Day (10 October 1972).

16. See “Historical Sketch,” P.E.N American Center Archives. Princeton University Library, http://libweb.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/pen.html (04 June 2005).

16. See “Historical Sketch,” P.E.N American Center Archives. Princeton University Library, http://libweb.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/pen.html (04 June 2005).

17. Stuart MacClennan, Letter to Paul Gabites (24 September 1964).

17. Stuart MacClennan, Letter to Paul Gabites (24 September 1964).

19. Francis M. Naumann, one authority on Duchamp’s personal correspondences, writes “I have never come across any references to Judge Julius Isaacs or to Betty Isaacs in my research through the extant Duchamp correspondence.” “Re: Duchamp correspondences- Betty and Judge Julius Isaacs/ New Zealand connections,” E-mail to the author (4 April 2005).

19. Francis M. Naumann, one authority on Duchamp’s personal correspondences, writes “I have never come across any references to Judge Julius Isaacs or to Betty Isaacs in my research through the extant Duchamp correspondence.” “Re: Duchamp correspondences- Betty and Judge Julius Isaacs/ New Zealand connections,” E-mail to the author (4 April 2005).

20. L. David Clark Jr., Letter to Cpt. J. Malcolm (13 November 1980).

20. L. David Clark Jr., Letter to Cpt. J. Malcolm (13 November 1980).

21. Julius Isaacs, “Receipt and release of the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand” (November 9 1981).

21. Julius Isaacs, “Receipt and release of the bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand” (November 9 1981).

22. Luit Bieringa, Personal interview with the author (17 May 2005).

22. Luit Bieringa, Personal interview with the author (17 May 2005).

23. However, this was not the first time works by Marcel Duchamp had arrived to New Zealand. 78 works from The Mary Sisler Collection toured the country in 1967.

23. However, this was not the first time works by Marcel Duchamp had arrived to New Zealand. 78 works from The Mary Sisler Collection toured the country in 1967.

24. Luit Bieringa, Letter to David Cark Jr (20 May 1981).

24. Luit Bieringa, Letter to David Cark Jr (20 May 1981).

25. See Dieter Daniels, “Marcel Duchamp: The Most Influential Artist of the 20th Century?,” Museum Jean Tinguely Basel. Ed. Marcel Duchamp. (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2002) 25-28.

25. See Dieter Daniels, “Marcel Duchamp: The Most Influential Artist of the 20th Century?,” Museum Jean Tinguely Basel. Ed. Marcel Duchamp. (Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2002) 25-28.

26. Naumann and Obalk, op. cit. 15. For a history of signed replicas and editions in this period see Naumann’s “Proliferation of the Already Made: Copies, Replicas, and Works in Edition, 1960-64,” Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 1999) 208-254.

26. Naumann and Obalk, op. cit. 15. For a history of signed replicas and editions in this period see Naumann’s “Proliferation of the Already Made: Copies, Replicas, and Works in Edition, 1960-64,” Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 1999) 208-254.

Bieringa, Luit. Personal Interview. 17 May. 2005

_____. Letter to L David Clark Jr. 20 May 1981. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Cage, John. “Untitled” poem. 20 April 2005. http://www.lcdf.org/indeterminacy/s.cgi?66.

Clark Jr., L. David. Letter to the Art Galleries and Museums Association of New Zealand Inc. 13 November 1980. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

_____. Letter to Cpt. J. Malcolm. 13 November 1980. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Daniels, Dieter. “Marcel Duchamp: The Most Influential Artist of the 20th Century?” Marcel Duchamp. Ed. Museum Jean Tinguely Basel. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2002.

Goldblatt, Rob. “Re: Betty Isaacs”. E-mail to the author. 17 April. 2005.

Heinemann, David. Personal Interview. 30 May. 2005.

“Historical Sketch.” P.E.N American Center Archives. Princeton University Library. 04 June 2005. http://libweb.princeton.edu/libraries/firestone/rbsc/aids/pen.html

“Isaacs Debut Show”. New York Times 12 Dec. 1953: 23.

Isaacs, Julius. Letter to Melvin Day. 10 Oct. 1972. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

_____. Estate of Julius Isaacs. “Receipt and release of the Bequest of Judge Julius Isaacs to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand.” November 9 1981. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Lensing, Mildred. “With Chisel or Spoon Mrs. Isaacs Creates.” Courier Journal

[Louisville] 8 Oct. 1955.

MacClennan, Stuart. Letter to Paul Gabites. 24 September 1964. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Naumann, Francis M. “Proliferation of the Already Made: Copies, Replicas, and Works in Edition, 1960-64)”. Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. Amsterdam: Ludion Press, 1999. 208-254.

_____. “Re: Duchamp correspondences- Betty and Judge Julius Isaacs/ New Zealand connections.” E-mail to the author. 4 April 2005.

_____. “Duchampiana II: Money Is No Object”. Art in America Mar. 2003: 67-73.

_____. “Marcel Duchamp: Money Is No Object. The Art of Defying the Art Market”. Tout-Fait: The Marcel Duchamp Studies Online Journal 2.5 (2003): News.

Naumann, Francis M and Obalk, Hector. Ed. Affect Marcel – The Selected Correspondence of

Marcel Duchamp. London: Thames and Hudson, 2000.

Schwarz, Arturo. The Complete Works of Marcel Duchamp. New York: Delano Greenidge Editions, 2000.

Taylor, Richard. Letter to Julius Isaacs. 21 July 1966. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Te Papa Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Museum art catalogue references: Betty Waistcoat, Item No: 2810, Accession No: 1983-0032-229; The Chess Players Item No: 2330, Accession No: 1983-0032-179. Te Papa Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Tomkins, Calvin. The World of Marcel Duchamp, 1887-. New York: Time Incorporated, 1966.

_____. Duchamp – a Biography. London: Pimlico, 1998.

William Doyle Galleries Inc. “Summary and appraisal of the Judge Julius Isaacs Bequest to the National Art Gallery of New Zealand.” 16 June 1980. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

“Women Sculptors at Galleries Here”. New York Times 12 Dec. 1953: 23.

Ziman, Vera. Letter to Luit Bieringa. 2 November 1981. Archive file MU00000-4-23-2. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Wellington, New Zealand.

Fig. 2-4, 6-8, 11, 15 © 2007 Succession Marcel Duchamp, ARS, N.Y./ADAGP, Paris.